![]()

1

A journey into political geography

Westminster Bridge in London is an interesting vantage point from which to start our journey into political geography. It will be a location familiar to many readers, but you can also find it by putting the coordinates 51º 30’ 6” N 0º 7’ 24” W into Google Earth. To the south-west is the Palace of Westminster, the seat of the British parliament and a symbol of the electoral politics that many people will first think of when ‘political geography’ is mentioned. Indeed, Westminster Bridge crosses the boundary between two parliamentary constituencies, reminding us that parliamentarians tend to be elected to represent particular geographical territories, and that the way in which these territories are drawn up and the geographical spread of votes across them can shape the outcome of elections. Across the River Thames is St Thomas’s Hospital, representing the function of the state in providing public services such as healthcare and education – objects of political debate in parliament, but also the places that we most commonly encounter the state on an everyday basis in our local communities.

To the north-east of Westminster Bridge is the old County Hall, formerly the headquarters of the Greater London Council until it was abolished in 1982 in an ideological struggle with the UK central government – represented by the offices of Whitehall directly across the river. Together with the new City Hall down-river, built when London was given an elected mayor in 2000, these are sites in the shifting internal political geography of the British state – reminding us that the subdivision of a nation-state into local territories and the distribution of power between different scales of governance are fluid and contested.

Following Whitehall to the north we come to Trafalgar Square, whose name and monumental centrepiece – Nelson’s Column – commemorate a British battle victory over France in the Napoleonic wars (as does the name of Waterloo railway station across the river). Rich in iconography, Trafalgar Square symbolises a discourse of British national identity that is nostalgic for imperial glory and encodes into the landscape the geopolitics of the nineteenth century. Yet, all around are reminders of the volatile geopolitics of the twenty-first century, not least the red London buses that were the target for a murderous al-Qaeda terrorist attack on 7 July 2005.

Round the river bend, the shimmering glass towers of the City of London form a different landscape of power, representing the dominance of global capitalism. The way in which the corporate offices dwarf the buildings of regulatory institutions such as the Bank of England resonates with the limited capacity of nation-states to control the global economy, and the political-geographical challenge of creating new forms of transnational governance. But places like the City of London also provide spaces for dissent. Near to the river the cruciform of St Paul’s Cathedral stands out, whose grounds were colonised by anti-capitalist ‘Occupy’ protestors in 2011, demonstrating the power of controlling and occupying space.

To the east of the City of London, the river passes the gentrified districts of Whitechapel and Stepney, the redeveloped docklands at Canary Wharf, and, a little inland to the north, the 2012 Olympic Park at Stratford. Here we encounter a more localised political geography – conflicts over the physical and social displacement of working class residents and local businesses for new elite developments and mega-events, and debates over the impact on community coherence. Further east, suburbs such as Plaistow and Barking host populations rich in ethnic diversity, with residents engaged in the everyday negotiation of the politics of identity and citizenship in a multicultural society. The streets and industrial estates of East London tell other stories of everyday political geography too: labour disputes over pay and conditions; struggles over the use of public spaces; community mobilisation and voluntary action to represent tenants’ interests, fight crime, and fill gaps in local services; and the gendered politics of the home and the workplace.

Returning to the river, we come finally to the Thames Flood Barrier at Woolwich Reach. Completed in 1982 to protect London from tidal flooding, it is a reminder of the threat of sea level rises with climate change and the challenge of environmental politics. Understanding political responses to climate change, the growth of transnational environmental campaigns and the negotiation of international agreements on the environment are increasing concerns for political geographers, as are the politics of managing our dwindling natural resources.

Our journey along the River Thames through London has presented a vivid and varied panorama of political geography, but it is not exceptional. Political geography can be encountered on a stroll through any city, town or village. James Sidaway (2009) illustrates this with his account of a walk through Plymouth, in south-west England, making connections to stories of imperialism and colonialism, global trade, twentieth-century geopolitics, urban development and gentrification, neoliberal housing policy and the politics of land access. In our own small college town of Aberystwyth in west Wales, a waterfront walk would pass a bridge blockaded in a pivotal protest for Welsh nationalism, the former offices of a regional development agency before territorial re-organisation, a diminished fishing fleet that prompts thoughts about the politics of resource management and the up-scaling of policy to the European Union, the ruins of a castle that would have dominated the mediaeval landscape of power as a symbol of English control, and an ornate war memorial reflecting the dark side of geopolitics and the pride and ambition of a provincial town.

Put simply, political geography is everywhere. From the ‘big P’ Politics of elections and international relations, to the ‘small p’ politics of social relations and community life, politics not only shapes and infiltrates our everyday lives, but is everywhere embedded in space, place and territory. It is this intersection of ‘politics’ and ‘geography’ that we understand as ‘political geography’ and which we seek to examine in its many diverse forms in this book.

Defining political geography

Political geographers have taken a number of different approaches to defining the field of political geography. To some, political geography has been about the study of political territorial units, borders and administrative subdivisions (Alexander 1963; Goblet 1955). For others, political geography is the study of political processes, differing from political science only in emphasis given to geographical influences and outcomes and in the application of spatial analysis techniques (Burnett and Taylor 1981; Kasperson and Minghi 1969). Both of these definitions reflected the influence of wider theoretical approaches within geography as a whole – regional geography and spatial science, respectively – at particular moments in the historical evolution of political geography and have generally been superseded as the discipline has moved on. Still current, however, is a third approach which holds that political geography should be defined in terms of its key concepts, which the proponents of this approach generally identify as territory and the state (e.g. Cox 2002). This approach shares with the earlier two approaches a desire to identify the ‘essence’ of political geography such that a definitive classification can be made of what is and what isn’t ‘political geography’. Yet, political geography as it is actually researched and taught is much messier than these essentialist definitions suggest. Think, for example, about the word ‘politics’. Essentialist definitions of political geography have tended to conceive of politics in very formal terms, as being about the state, elections and international relations. But, ‘politics’ also occurs in all kinds of other, less formal, everyday situations, many of which have a strong geographical dimension – issues about the use of public space by young people for skateboarding, for example, or about the symbolic significance of a landscape threatened with development. Whilst essentialist definitions of political geography would exclude most of these topics, they have become an increasingly important focus for geographical research.

As such, a fourth approach has been taken by writers who have sought to define political geography in a much more open and inclusive manner. John Agnew, for example, defines political geography as simply ‘the study of how politics is informed by geography’ (2002: 1; see also Agnew et al. 2003), whilst Painter and Jeffrey (2009) describe political geography as a ‘discourse’, or a body of knowledge that produces particular understandings about the world, characterised by internal debate, the evolutionary adoption of new ideas, and dynamic boundaries. As indicated above, the way in which political geography is conceived of in this book fits broadly within this last approach.

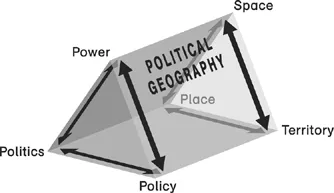

We define political geography as a cluster of work within the social sciences that seeks to engage with the multiple intersections of ‘politics’ and ‘geography’, where these two terms are imagined as triangular configurations (Figure 1.1). On one side is the triangle of power, politics and policy. Here power is the commodity that sustains the other two – as Bob Jessop puts it, ‘if money makes the economic world go round, power is the medium of politics’ (Jessop 1990a: 322) (see Box 1.1). Politics is the whole set of processes that are involved in achieving, exercising and resisting power – from the functions of the state to elections to warfare to office gossip. Policy is the intended outcome, the things that power allows one to achieve and that politics is about being in a position to do.

Figure 1.1 Political geography as the interaction of ‘politics’ and ‘geography’

The interaction between these three entities is the concern of political science. Political geography is about the interaction between these entities and a second triangle of space, place and territory. In this triangle, space (or spatial patterns or spatial relations) is the core commodity of geography. Place is a particular point in space, whilst territory represents a more formal attempt to define and delimit a portion of space, inscribed with a particular identity and characteristics. Political geography recognises that these six entities – power, politics and policy, space, place and territory – are intrinsically linked, but a piece of political geographical research does not need to explicitly address them all. Spatial variations in policy implementation are a concern of political geography, as is the influence of territorial identity on voting behaviour, to pick two random examples. Political geography, therefore, embraces an innumerable multitude of interactions, some of which may have a cultural dimension that makes them also of interest to cultural geographers, some of which may have an economic dimension also of interest to economic geographers, some of which occurred in the past and are also studied by historical geographers. To employ a metaphor that we will explain in Chapter 2, political geography has frontier zones, not borders.

In this book we explore these various themes and topics by drawing on and discussing contemporary research in political geography. The case studies and examples that we refer to are taken predominantly from books and journal articles published in the last twenty years, the most recent of which may be regarded as sitting at the ‘cutting edge’ of political geography research. However, current and recent work in political geography of this kind does not exist in a historical vacuum. It builds on the foundations of earlier research and writing, advancing an argument through critique and debate and through the exploration of new empirical studies that allow new ideas to be proposed. Knowing something about this genealogy of political geography helps us to understand the nature, approach and key concerns of contemporary political geography. To provide this background, the remainder of this chapter outlines a brief history of political geography, from the emergence of the sub-discipline in the nineteenth century through to current debates about its future direction.

BOX 1.1 POWER

Put simply, power is an ability to get things done, yet there are many different theories about what precisely power is and how it works. In broad terms there are two main approaches to conceptualising power. The first defines power as a property that can be possessed, building on an intellectual tradition that stems from Thomas Hobbes and Max Weber. Some writers in this tradition suggest that power is relational and involves conscious decision-making, as Robert Dahl describes: ‘A has power over B to the extent that he can get B to do something that B would not otherwise do’ (Lukes 1974: 11–12). Others have argued that power can be possessed without being exercised, or that the exercise of power does not need conscious decision-making but that ensuring that certain courses of action are never even considered is also an exercise of power. The second approach contends that power is not something that can be possessed, as Bruno Latour remarks: ‘When you simply have power – in potentia – nothing happens and you are powerless; when you exert power – in actu – others are performing the action and not you. … History is full of people who, because they believed social scientists and deemed power to be something you can possess and capitalise, gave orders no one obeyed!’ (Latour 1986: 264–5). Instead, power is conceived of as a ‘capacity to act’, which exists only when it is exercised and which requires the pooling together of the resources of a number of different entities.

A brief history of political geography

The history of political geography as an academic sub-discipline can be roughly divided into three eras: an era of ascendency from the late nineteenth century to the Second World War; an era of marginalisation from the 1940s to the 1970s; and an era of revival from the late 1970s onwards. However, the trajectory of political geographic writing and thinking can be traced back long before even the earliest of these dates. Aristotle, writing some 2,300 years ago in ancient Greece, produced a study of the state in which he adopted an environmental deterministic approach to considering the requirements for boundaries, the capital city, and the ratio between territory size and population; whilst, the Greco-Roman geographer, Strabo, examined how the Roman Empire was able to overcome the difficulties caused by its great size to function effectively. Interest in the factors shaping the form of political territories was revived in the European ‘Age of Enlightenment’ from the sixteenth through to the eighteenth centuries, as writers combined their new enthusiasm for science and philosophy with the practical concerns generated by a period of political reform and instability. Most notable was Sir William Petty, an English scientist and economist who in 1672 published The Political Anatomy of Ireland in which he explored the territorial and demographic bases of the power of the British state in Ireland. Petty developed these ideas further in his second book, Essays in Political Arithmetick, begun in 1671 and published posthumously, which outlined theories on, among other things, a state’s sphere of influence, the role of capital cities, and importance of distance in limiting the reach of human activity. In this way Petty foreshadowed the concerns of many later political geographers, but his books were, like other geographical writing of the time and the classical texts of Strabo and Aristotle, popular works of individual scholarship by polymaths, which did not stand as part of a coherent field of ‘political geography’. To find the real beginnings of ‘political geography’ as an academic discipline we need to look to nineteenth-century Germany.

The era of ascendency

The significance of Germany as the cradle of political geography lies in its relatively recent formation. Modern Germany had come into being as a unified state only in 1871 and under ambitious Prussian leadership sought in the closing decades of the nineteenth century to establish itself as a ‘great power’ on a par with Britain, France, Austria-Hungary and Russia. However, Germany was constrained by its largely landlocked, central European location, which restricted its potential for territorial expansion. In these circumstances, ideas about the relationship between territory and state power became key concerns for Germany’s new intellectual class and in particular for Friedrich Ratzel, sometimes referred to as ‘the father of political geography’.

Much of Ratzel’s work was driven by a desire to intellectually justify the territorial expansion of Germany and in writing such as Politische Geographie (1897) he embarked on a ‘scientific’ study of the state (see Bassin 1987). Ratzel drew on earlier politi...