![]()

Chapter 1

Bajo la Santa Federación: Representations of Rosas’s Tyranny

In the prologue to the edited collection of the scripts of the first instalment of the Bajo la Santa Federación series, Blomberg and Viale Paz expressed their motivation for bringing the Rosas era to the radio:

Al realizar el plan de “Bajo la Santa Federación” fué nuestro propósito llevar a efecto una evocación integral de la época célebre; revivir los personajes de aquel tiempo, cada uno en su medio: payadores y mazorqueros, pulperos y soldados, los famosos negros de los candombés de Rosas, los unitarios perseguidos, militares y poetas; los hacendados, los paisanos, las turbas hormigueantes de las calles, las plazas, los mercados, los cuarteles, las pulperías, los barrios numerosos; los carnavales, las semanas santas, los fastos pintorescos y ruidosos de la Federación, bajo la sombra roja y avasalladora del Restaurador de las Leyes.

[In carrying out the Bajo la Santa Federación plan, our intention was to create a complete evocation of the famous era: to revive the characters of that time, each one in their own setting: troubadours and mazorqueros, landlords and soldiers, the famous black men of Rosas’s candombé dances, the persecuted Unitarians, military men and poets; the landowners, the peasants, the crowded streets, the squares, the markets, the barracks, the taverns, the many neighbourhoods, the carnivals, the Easter weeks, the noisy and picturesque pageants of the Federation, under the red and oppressive shadow of the Restorer of Law.] (5)1

As one of the most inflammatory periods of Argentine history, the Rosas era has a wealth of dramatic potential when used as a setting for literary and cultural production. This, combined with an enduring cultural memory of Rosas as a brutal tyrant, has made it an attractive setting for several generations of writers. Blomberg and Viale Paz’s description of the themes which evoke the Rosas era pertains to a literary and cultural tradition of representations of the Rosas regime stretching back to the time of the regime itself. In the liberal tradition, these elements are the cultural markers of the regime which identify it as a tyranny. Nevertheless, Blomberg and Viale Paz’s presentation of the Rosas era is not restricted to the creation of a tableau which evokes the period. In their radio serial, the writers subscribe to the ‘official’ historical evaluation of the regime as first presented in the works of the Generation of 1837. Bajo la Santa Federación of 1933 is one example in the long trajectory of cultural productions set in the Rosas era which begins with Mármol’s Amalia of 1851 and continues through to Gutiérrez’s Los dramas del terror of the 1880s. The radio serial conflicts with the work of the Historical Revisionists in the década infame who promote a re-evaluation of the Rosas era seeking to rescue Rosas’s legacy from its damning treatment in liberal history. From these two very different evaluations of the past emerge conflicting conclusions as to Argentina’s future path. Blomberg and Viale Paz do not mention the work of the Historical Revisionists, just as these intellectuals never reference the radio serials set in the Rosas era. Despite the points of connection between the two bodies of work undertaken at the same time, the Historical Revisionists and the radio writers are working within such different spheres that neither group recognises the endeavours of the other.

Blomberg became interested in the Rosas era around the same time as the intellectuals who would become the Historical Revisionists began to turn their attention to this period. On 27 September 1930 Blomberg premiered a play based on the lyrics of his waltz ‘La pulpera de Santa Lucía’ of 1929 and another of Blomberg’s plays set in the Rosas era, La mulata del Restaurador, opened on 30 June 1932. In their prologue, Blomberg and Viale Paz maintain that it is their ‘novela histórica radio-teatral’, Bajo la Santa Federación, which led a renewed interest in Rosas in the cultural production of the 1930s. They state that shortly after the serial’s début in Buenos Aires, ‘nuestra producción se difundía en todo el país, conquistaba todas las clases sociales y despertaba, según creemos, un nuevo y profundo interés hacia la época de Rosas, “tan zarandeado”, según algunos críticos teatrales y literarios’ [our production was transmitted throughout the country, conquering all social classes and inspiring, or so we believe, a profound interest in the Rosas era which some theatre and literary critics considered to be have been ‘abused’] (5). The success of Bajo la Santa Federación ensured that other radio stations would soon be transmitting Rosas-era serials which also followed ‘official’ history in their depictions of the dictator and his regime. One notable example was El puñal de la mazorca written by Alfredo E. Orofino, Eduardo Zucchi and Atilano Ortega Sanz and transmitted from April to August 1934 on LR3 Radio Nacional. The scripts of only the first 23 episodes survive in the archives of Argentores. These were published by Editorial Talia as part of the series Biblioteca teatral argentina. In the writers’ ‘Palabras preliminares’, Orofino et al. state: ‘Toda época de sangre ha sido rica en pasajes de amores truncados, idilios interrumpidos y platónicos episodios. Pero el período “rosino” ha sido quizá uno de los más ricos de estos últimos siglos.’ [Every bloody era has been rich in stories of frustrated love, interrupted romances and platonic episodes. But the Rosas era has perhaps been one of the richest in the last centuries.] It is clear that Orofino et al. intend to root their presentation of the Rosas era in the liberal tradition: ‘nuestro propósito es ofrecer la “época de la tiranía” descripta de manera fiel y sin ambajes’ [our intention is to offer a faithful and unambiguous description of the ‘era of tyranny’].

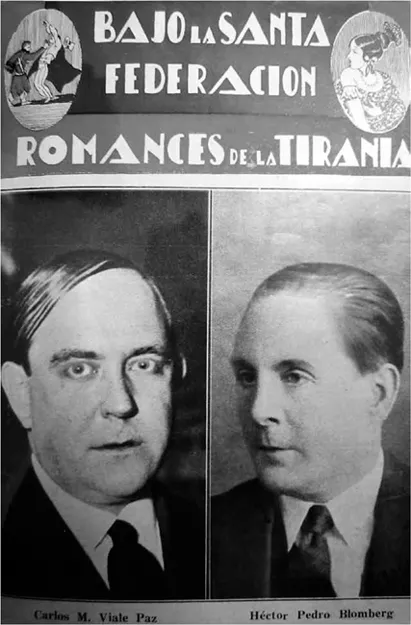

Fig. 1.1 Viale Paz and Blomberg on the cover of the Bajo la Santa Federación scripts magazine. Image taken from the same magazine published by Blas Buccheri, 1933.

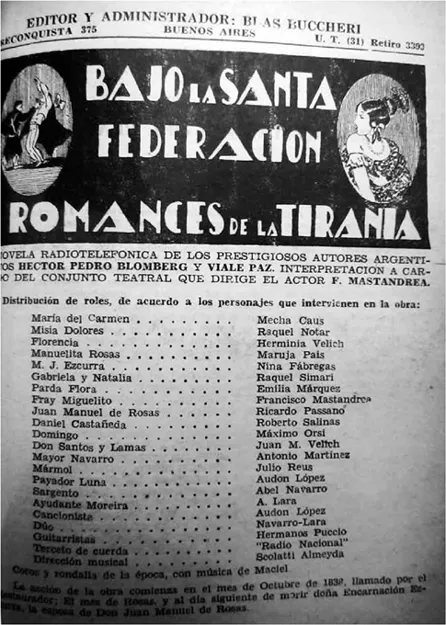

Fig. 1.2 The cast list of Bajo la Santa Federación. Blas Buccheri, 1933.

Civilisation and Barbarism: The porteños Versus the caudillos in the Process of National Organisation

The process of national organisation from Independence in 1810 and the ideological conflict between the Federalists and the Unitarians provides important historical contextualisation for an analysis of the liberal condemnation of the Rosas regime. It was only after the fall of Rosas and the political triumph of the liberals that the ‘official’ liberal history which casts Rosas as a tyrant could be written. However, the basis for this ‘official’ history already existed in the texts of Rosas’s opponents written from exile during the regime. These texts condemned Rosas for his brutality but also for his Federalism which places him on the side of barbarism and pits him against the civilisation advocated by the liberals. The dichotomy of civilisation and barbarism is at the core of ‘official’ history and is one of the foundational discourses that have passed into Argentine cultural memory. The dichotomy was enshrined in Sarmiento’s Facundo, published in Chile in 1845. Facundo, which remains engrained in the national imaginary as one of Argentina’s most significant foundational texts, was first published under the title of Civilización y barbarie: Vida de Juan Facundo Quiroga. Aspecto físico, costumbres y hábitos de la República Argentina and in later editions appears as Facundo o civilización y barbarie en las pampas argentinas. In terms of genre, Facundo falls into various categories as it incorporates sociohistorical essay and elements of romanticism into what is ostensibly a biography of the Federalist caudillo Juan Facundo Quiroga. By focusing on Facundo as an example of the provincial caudillos, Sarmiento is able to examine the reasons for Rosas’s lamented rise to power and comment on the disastrous consequences of his rule for Argentina.

In Facundo, Sarmiento argues that the divide between rural and urban societies at the root of the conflict between the Federalist and Unitarian parties was already present before Independence in 1810. He describes the existence of two rival and incompatible societies which encompassed two distinct civilisations: ‘one Spanish, European, cultured, and the other barbarous, American, almost indigenous’ (104; 77).2 When the leaders of the May revolution declared independence from Napoleonic Spain in Buenos Aires in 1810, they did so on behalf of the entire Viceroyalty but the lack of cohesion within this vast territory soon became apparent (Shumway 22). As the fledgling nation-state struggled to emerge and take control, caudillismo was able to take hold as a system of unofficial provincial leadership based on the practices of clientelism (Williamson 238). The view held by Sarmiento and by subsequent liberal historians is that the caudillos were feudalist despots who hindered the progress of the nation and the political consolidation of the national territory. For the Unitarians, Rosas was the ultimate caudillo and for Sarmiento in particular, the caudillo was both the cause and the reflection of Argentina’s barbarism (93; 71). Caudillismo is at the heart of the divide between the provinces and the port city of Buenos Aires as, in defending their provinces from porteño influence and intervention, the caudillos posed a threat to the plans of the Buenos Aires elite.

Mariano Moreno, the secretary of the Primera Junta, the governing body that replaced the Viceroy in Buenos Aires, died at sea in 1811. Shumway identifies the first post-Independence porteño intellectuals as ‘morenistas’ and as the precursors to the Unitarians as they looked to importing European culture and values into the new nation to combat the backwardness of the caudillos and their provinces (47). In 1816, the Congress of Tucumán declared the independence of the United Provinces of the River Plate. The absence from this Congress of the Banda Oriental – now Uruguay – and the provinces of Santa Fe, Corrientes and Entre Ríos aptly displays the lack of cohesion amongst the regional leaders of the time. By 1819 Buenos Aires was already widening the division between the port and the provinces when it drafted a Unitarian, Centralist constitution. The constitution was opposed by a group of provincial caudillos who defeated the government of Buenos Aires in the Battle of Cepeda in 1820 (Scheina 114). The caudillos took power in their respective provinces and several provinces, including Entre Ríos, declared themselves independent republics (Shumway 93).

In February 1826, Bernardino Rivadavia was appointed President of the United Provinces by the Congress in Buenos Aires and the following month, Buenos Aires was declared the nation’s capital.3 In order to encourage modernisation, Rivadavia promoted the ‘morenista’ ideals of European immigration, free trade and foreign investment. Congress subsequently ‘approved a constitution for the nonexistent state’ which greatly angered the provincial caudillos who had not been consulted (Criscenti 101). Among the ranks of the conservative, landed oligarchy who opposed these ideals was the powerful Anchorena family to whom Rosas was related. Sarmiento’s praise for Rivadavia serves to highlight his contempt for Rosas and to underline the central dichotomy of civilisation and barbarism. In Facundo he writes that ‘Rosas and Rivadavia are the two extremes of the Argentine Republic, which is bound to savages by the Pampas and to Europe by the Río de la Plata’ (179; 124). Following Rivadavia’s resignation, the Federalist-dominated legislature of the province of Buenos Aires elected Manuel Dorrego to the post of Governor in 1828 (Criscenti 102). In December 1828, the Unitarian and hero of the independence movement, Juan Lavalle, staged a coup against Dorrego’s elected government, citing as justification Dorrego’s signing of a treaty with Brazil that made the Banda Oriental an independent nation. Lavalle became governor of the Province of Buenos Aires in a rigged election, dissolved the Federalist-dominated provincial legislature and had Dorrego executed without trial, severely undermining the Unitarians’ claims to moral superiority over the Federalist caudillos. The Federalists, led by Juan Manuel de Rosas and López of Santa Fe, defeated Lavalle who then fled to Montevideo in April 1829 (Shumway 115–17).

For Rosas’s supporters, the new Governor of the Province of Buenos Aires emerged as a hero who had saved the province from anarchy after the execution of Dorrego and the defeat of Lavalle. Upon his election by the reinstated Federalist-dominated provincial legislature, Rosas was given ‘facultades extraordinarias’ [extraordinary powers] which amounted to near dictatorial authority over his province for his three-year term (Shumway 117). Rosas had been one of the most prominent provincial Federalists since the late 1820s. His provincial army was comprised not just of the usual gaucho cavalry but was also supplemented with an infantry of urban poor from the port of Buenos Aires (Scheina 115). They thought that Rosas would look after their interests and the elites saw him as the man to save Buenos Aires from anarchy. However, as an estanciero and a member of the conservative landowning oligarchy, Rosas would put his regime at the service of the interests of his class. Ironically, by running Buenos Aires in true caudillo style, Rosas proceeded to achieve the longstanding Unitarian goal of consolidating Buenos Aires as the site of power of the Republic.

By 1831, the individual provinces were acting as independent, sovereign states, further hindering the ongoing attempts at national organisation. In that year, Rosas’s Unitarian opponents, along with the caudillo Facundo Quiroga, sought Bolivia’s help to fight Rosas, offering the provinces of Jujuy and Salta in exchange. Rosas responded with the Treaty of the Littoral which united Buenos Aires and the other provinces together in a confederation. By the end of 1832, 13 provinces had signed the treaty and had authorised Buenos Aires to conduct their foreign affairs. While Rosas’s priority was clearly to protect the economic and political interests of his own increasingly isolated province, this treaty was a step towards the formation of the nation-state, not least because those residing within La Santa Federación [the Holy Federation], as Rosas promoted it, began to call themselves Argentines (Criscenti 104–5).

During his first term as governor, Rosas exceeded expectations and succeeded in restoring order with the help of some authoritarian measures such as restriction of the press (Shumway 117). To avoid being accused of abusing the powers given to him by the legislature, he was careful to resign as agreed in November 1832 and promptly left the city for his estancia. For the following three years, Rosas undertook a military campaign to extend the territory of the Federation into Indian lands (Rock, Argentina 1516–1987 106). In his absence, chaos enveloped Buenos Aires once more and in 1834 the legislature voted to reappoint Rosas. As they were unwilling to give him absolute authority, Rosas declined the offer (Scheina 118). In the meantime his wife, Encarnación Ezcurra, began orchestrating a campaign for her husband’s ‘restoration’ as governor. Capitalising on the support of the popular classes for Rosas she organised the mass movement of the Sociedad Popular Restauradora whose provincial members undertook an armed siege of Buenos Aires whilst Ezcurra mobilised supporters from within the city (Lynch 160–61). This episode was later recast by the Rosas propaganda machine as the ‘Revolución de los Restauradores’.4

After negotiations, the legislature agreed to invest Rosas with ‘la suma del poder público’ [the plenitude of public power] for his second term as governor in March 1835 (Scheina 118). For the next 17 years Rosas ruled the province of Buenos Aires and extended his control to other parts of the Argentine territory. During this time, in place of elections Rosas would routinely offer his resignation to his ‘hand-picked congress’ for them to invite him to remain in office (Shumway 12...