Beginnings

Unlike some twentieth-century architects for whom theoretical discourse has formed a necessary base for action, James Stirling was always suspicious of theory per se. He called it ‘bullshit’, always rejecting ideology for the process of design itself. It was by tackling architectural problems that he developed his understanding of his art, like Lutyens, relying on the security of his intuition. And, like Lutyens, he wrote little and expounded rarely and then briefly, about his work, distrusting those who wrote about him in a trendy, obscure fashion.

Stirling began his course in architecture at Liverpool University in September 1946, and as an ex-serviceman was allowed to complete the course in four years. His mature approach can be linked to his beginning architecture school following war service. He was recovering from wounds sustained in the D-Day landings, convalescing at Harewood House in Yorkshire, when he decided to become an architect. As Mary Stirling points out; ‘this was a tremendously interesting generation because of the social mix-up; people from all classes were invalided in grand country houses and exposed to unfamiliar situations’.1 Exposure to other existential conditions of war and wealth gave an entirely different perspective to the university experience. Instead of being carefree undergraduates, enjoying university life, these veterans were very seriously pursuing a professional qualification. They were determined to make the most of the educational opportunity.

Stirling has described the atmosphere at the Liverpool school when he was there:

The School of Architecture was in a tremendous ferment as the revolution of modern architecture had just hit it, secondhand and rather late. There was furious debate as to the validity of the modern movement, tempers were heated and discussion was intense. Some staff resigned and a few students went off to other schools; at any rate I was left with a deep conviction of the moral rightness of the new architecture.2

Stirling’s Liverpool background was important to his development in several ways. Under Sir Charles Reilly, the School of Architecture had become a leading academy in the Beaux-Arts tradition and in the days of his successor, Lionel Budden, Liverpool students carried off the Rome Prize with monotonous regularity. As a student, Stirling was exposed to an eclectic mix of sources, historical and modern, and as he later recalled ‘one had to be good in many styles. In the first year we did renderings of classical orders followed by the design of an antique fountain, and at the end of that year we had to design a house in the manner of C.F.A. Voysey, quite a span of history’.3

Influences at Liverpool

He explains how ‘we oscillated backwards and forwards between the antique and the just arrived Modern Movement’ a pattern of oscillation between past and present that became evident in the work of his late period. He was most influenced by Le Corbusier’s Towards a New Architecture and Saxi and Wittkower’s British Art and the Mediterranean, two sides of the architectural coin that remind us of his open-ended viewpoint.

The influence of these two books, at opposite poles in the architectural spectrum, does much to explain Stirling’s approach to his vocation. Saxi and Wittkower, focusing on the eighteenth century, set out to show ‘the extent to which English art is indebted to Greece and Italy’.4 This lavishly illustrated book traces the classical derivation of much English art and architecture, and the Mediterranean influence is traced back long before the Roman invasion, showing sculpture, art and architecture that have permeated the English culture for over 2,000 years. Illustrating Italian models used by Inigo Jones and Wren’s reliance on Rome for his design of St Paul’s Cathedral, the book argues for a deep empathy between England and the Mediterranean region, an empathy felt by Stirling at a visceral level. His love of Italy extended throughout his life, nourished by his enjoyment of its artists, architects and towns and cities.

The book also celebrates the achievements of English architects such as Sir John Vanbrugh, who ‘possessed a sense not only for the arrangement and piling up of masses, but also for what might be called architectural drama to a larger degree than any other English architect’. The authors cite Vanbrugh’s Belvedere at Claremont House, Esher, in Surrey (1715): ‘The bastion-like belvedere, with its four towers is a good example of Vanbrugh’s peculiar archaism, which is a free interpretation of medieval castle architecture’, Vanbrugh’s architecture being ‘conceived in blocks and designed to be seen from many viewpoints’.5

Given Stirling’s propensity towards the bold and dramatic, and his love of historic architecture, selection of such a book is not surprising. Nor is his other choice, Le Corbusier’s Towards a New Architecture, which offered the theoretical basis for the works illustrated in his Oeuvre Complète series. Two books, one revering an English tradition, the other a poetic and impassioned plea for an architecture that would capture the spirit of the twentieth century, provided the greatest influence on the young James Stirling.

The range of his interests is revealing, and included Mackintosh and Hoffman, the Italian rationalists, and later, when he moved to London, Hawksmoor, Archer and Vanbrugh, these architects admired for ‘the ad-hoc technique which allowed them to design with elements of Roman, French and Gothic sometimes in the same building ’.6

In 1948 Stirling was selected as one of three students to visit the United States, seeing buildings by Wright, Gropius, Breuer, Howe and Lescaze and other modernists. On this visit he found the turn-of-the-century shingle houses of New Haven more interesting than Saarinen or SOM – the current heroes.7 He was impressed by a ‘limited period of Frank Lloyd Wright’s production, particularly the concrete block houses around Los Angeles’ and he noted the ‘way out’ aspect of New York Art Deco buildings such as the Chrysler Tower. He also admired Wright’s Johnson Wax HQ at Racine, Wisconsin, but was not impressed by Aalto’s Dormitories at MIT.

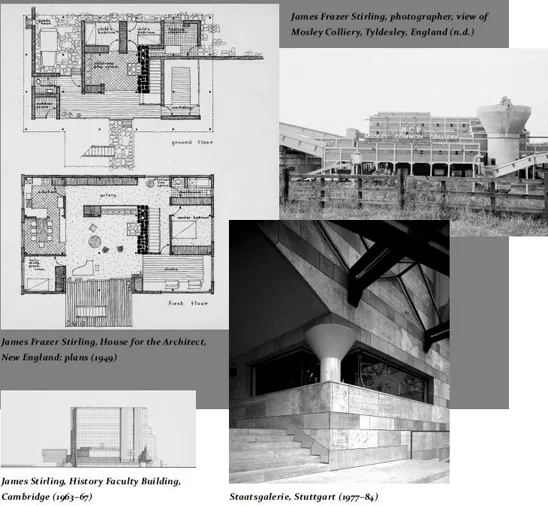

Interests in English castles, French chateaux, Bavarian Roccoco, Italian gardens, Venetian palazzi and English country houses confirm the range of Stirling’s eclecticism. He revealed this at the RIBA on receiving the Royal Gold Medal for architecture in 1980 and illustrated his talk with his German competitions, the extension to Rice University School of Architecture and the Stuttgart Staatsgalerie, examples that inferred easily discernible connections between the catholicity of his sources and the works themselves.

Stirling’s architectural education was never confined to academe, and when he moved to London in the autumn of 1950, he learned about the Russian Constructivists; he ‘devoured’ a book on Asplund and in the early fifties he developed an interest ‘in all things vernacular from the very small – farms, barns and village housing to the very large – warehouses, industrial buildings, engineering structures, including the great railway and exhibition sheds’.

He later became interested in the ‘stripey brick and tile architects like Butterfield, Street and Scott’. He also enjoyed the Soane Museum, Neo-classical architects like Candy and Goodridge and their German counterparts, Gilly, Weinbrenner, Von Klenze and Schinkel.8

The Liverpool and Manchester schools

Several of Stirling’s student projects at Liverpool University have survived and are preserved in the archive of the James Stirling Foundation.9 As my architectural training at Manchester University began in 1951, the year after Stirling qualified, Stirling’s work, not dissimilar in design technique or presentation from the ongoing approach at Manchester, affords a fascinating area of comparison. Each school at that time had a strong Beaux-Arts bias; planning and presentation were important and the Classical Composition, rendered in sepia, was a key subject of study as was shadow projection in the form of sciagraphy.

There was a strong academic bias to each school and the history of architecture formed the bedrock of understanding. Manchester was directed during the post-Second World War period by Reginald Annandale Cordingley, a Rome scholar in 1923, who encouraged a thorough grounding in historical studies. Leslie Martin’s Masters thesis formed part of this tradition and Thomas Howarth completed his doctoral study of Charles Rennie Mackintosh whilst teaching the first year at Manchester. But Liverpool had an emerging academic star of prescient brilliance in the person of Colin Rowe, who became a member of staff in 1948 having studied at the Warburg Institute under Rudolf Wittkower. Mary Stirling cites Rowe as ‘a tremendous influence’ on Stirling, introducing him to the view that modern architecture could be linked to the Italian Renaissance and Mannerism.10 Rowe’s article ‘The mathematics of the ideal villa’ alerted Stirling to a mathematical relationship between Palladio’s Villa Malcontenta and Le Corbusier’s Villa Stein de-Monzie. Rowe’s teaching enabled Stirling to see the Modern Movement through a filter of informed historical awareness, alerting him to that inclusive view of architecture that was to colour all his thinking.

It was an annoyance at Manchester that Liverpool managed to win the Rome Scholarship in Architecture so many times, a tide that turned in the fifties with a succession of Manchester wins that included Michael McKinnel (later a member of the team that won the Boston City Hall competition). Norman Foster was a student at Manchester at this time, evidence of the educ...