![]()

1

Strategic Thinking

There is a fundamental distinction to be made between two kinds of thinking: figuring out what we would like to achieve, and working out how to achieve it. Put another way, there is a key difference between strategy on the one hand and execution on the other. Strategy is about determining our overall aims; execution comprises everything that follows once we’ve decided – the practical activities required to put our plans into action.

It is natural to assume that we would spend a lot of time on strategy before we turned our attention to execution – however successful we might be in carrying out our plans, what really counts is having the right plans to work from in the first place. Our results can only be as good as the aims that first led to them.

But there is a paradoxical aspect to the way our minds operate: as a general rule, we’re much better at execution than at strategy. We appear to have an innate energy for working through obstacles to our goals and an equally innate resistance to pausing to understand what these goals should rightly be. We seem to be as lackadaisical about strategy as we are assiduous about execution.

We see the outcome of this bias across many areas. We concentrate more on making money than on figuring out how to spend it optimally. We put a lot more effort into becoming ‘successful’ than into assessing how dominant notions of success could make us content. At a collective level, corporations are much more committed to the efficient delivery of their existing products and services than on stepping back and asking afresh what the company might truly be trying to do for their customers. Nations are more concerned with growing their GDP than with probing at the benefits of increased purchasing power. Humanity is vastly better at engineering than philosophy: our planes are a good deal more impressive than our notions of what we should travel for; our abilities to communicate definitively outstrip our ideas of how to understand one another.

In every case, we prefer to zero in on the mechanics, on the means and the tools rather than on the guiding question of ends. We are almost allergic to the large first-order enquiries: what are we ultimately trying to do here? What would best serve our happiness? Why should we bother? How is this aligned with real value?

There are tragic consequences to this over-devotion to execution. We rush frantically to fulfil hastily chosen ends; we exhaust ourselves blindly in the name of sketchy goals; we chain ourselves to schedules, timelines and performance targets. All the while, we avoid asking what we might really need in order to flourish and so frequently learn, at the end of a lifetime of superhuman effort, that we had the wrong destinations from the start.

Perhaps it should not surprise us that our minds have such a pronounced bias towards executive labour over strategic reflection. From an evolutionary perspective, mulling over strategic questions was never a high priority. For most of history, the strategic goals would have been obvious: to find sufficient things to eat, to reproduce, to get through the winter and to keep the tribe safe from attack. Execution was where all the urgent and genuine difficulties lay: how to light a fire in wet weather; how to make sharper arrowheads; where to find wild strawberries or the right leaves to calm down an inflammation. We are the descendants of generations that made a succession of complex discoveries in the service of a few basic goals. Only in the conditions of modernity – where we are surrounded by acute choices as to what to do with our lives and when our aim is happiness rather than basic survival – have strategic questions become at once necessary and costly to avoid.

Little about our formal education has prepared us for this development. At school, ‘working hard’ still means dutifully following the curriculum, not wondering whether it happens to be correct. ‘Why should we study this subject?’ sounds, to most teachers, like an insult and a provocation, rather than the birth of an admirably speculative mindset. Once we start employment, most companies want the bulk of their employees to execute orders rather than reflect on their validity. We might be reaching middle age before we are granted the first formal incentives to think strategically.

Even in daily life, raising strategic questions can feel tiresome and odd. To ask ‘what’s the point of doing this?’ is easy to mistake for a piece of provocative negativity. If we challenge our acquaintances with any degree of seriousness with questions such as: ‘What is a good holiday?’, ‘What is a relationship for?’, ‘What is a satisfying conversation?’ or ‘Why do we want money?’, we risk coming across as absurd and pretentious – as though such large questions were by definition unanswerable.

The real dangers lie in never daring to raise such questions. We already possess fragmentary, disorganised but important information that could help us to make progress with the larger strategic dilemmas. We have already been on a sufficient number of holidays and shopping trips; we have already had some relationships and been through a number of career shifts; we have had a chance to observe the connections between what we do and how we feel. Therefore, at least in theory, we have gathered the necessary material from which to draw rich conclusions as to our happiness and our purpose, as to meaning and the right human ends. We have the data; the challenge is to process it by running it through the sieve of the larger questions.

We should dare to move the emphasis of our thinking away from execution and towards strategy.

Mental Manoeuvre

1. An immediate step is to grow more conscious of the way we presently spend our time: we might be devoting 95% of our waking hours to execution and a mere 5% to strategy. Acknowledging the unfair bias, we should strive to ensure that at least 20% of our efforts is henceforth devoted to reflecting on the deeper ‘why’ questions before we allow ourselves to ‘relax’ into the more familiar and more routine work of execution.

2. We should observe how often and how naturally we devote our time to executing our ideas before we have submitted them to adequate scrutiny. We should note our discomfort around questions like: Why is this a worthwhile effort? Where will I be in a few years if this goes right? How is this connected with what fulfils me? What is the point here? We should watch our comparative enthusiasm for launching ourselves into projects in a hurry, for fretting only about the lower-level procedural hiccups and for ensuring that we are too ‘busy’ ever to leave time for reflection. We should grow suspicious of our covert devotion to rush over enquiry.

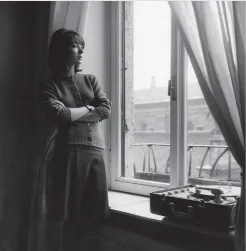

3. To accompany us in this, we need to redraw where prestige is accorded, to downgrade the glamour that presently clings to frantic busy-ness and to raise, to a corresponding degree, the image of speculative reflection. We need a new collective sense of what hard work might involve and even what it might look like. It won’t necessarily be the person who runs from meeting to meeting or juggles international phone calls who is genuinely engaged in working hard; it might be the person sitting at the window, gazing out at the clouds, occasionally cupping their head in their hands and writing something down in a little notebook.

Who is really working?

4. We need support with how uncomfortable strategic thinking can feel. We need to be reassured that we aren’t unusually wicked or flighty to be tempted to act rather than think, and should forgive ourselves for the strength of our wish to avoid all large first-order questions. We need encouragement to stick at probing the point and the meaning even when the overwhelming desire is to bury ourselves in correspondence or scan the news. We need to notice how oddly and humblingly lazy we are where it really counts.

Why is strategic thinking so hard?

In the Middle Ages, it was widely agreed that the most important thing to think about was God. Today, the subject most of us have to focus our attention on is our purpose. But in the Middle Ages, leading figures were prepared to accept that prolonged non-distracted attention was an arduous demand to make of our inherently fragile and wayward psyches. They knew how much our minds long to flee themselves, and realised that one might need to institute some dramatic-looking steps to help us to keep our focus. One of these important moves was the invention of the monastery.

The monastery made a range of extreme-sounding innovations in the arena of non-distraction. It proposed that, to keep the mind clear, one might need to live far removed from towns and cities, usually on the side of a mountain or cliff or in a sparsely inhabited stretch of countryside. As a continual reminder of the importance of thinking, the architecture would have to be solemn, grand and imposing. The walls were to be high and thick without many doors or picture windows giving out onto the wider world.

There might need to be secluded courtyards and inner fountains to calm the mind with the sound of trickling water. Bedrooms would have to be sparse, equipped only with a bed and a desk – but still uplifting and well constructed.

Medieval Christianity developed rules about how to live in monastic buildings. One of the earliest and most influential rule-setters was a Roman nobleman living at the end of the 5th century by the name of Benedict. He founded a number ...