![]()

CHAPTER 1

THE GEOGRAPHY, ENVIRONMENT AND PEOPLE OF NUBIA

The land of Nubia stretching along the river Nile from the first cataract southwards has never been very closely or accurately defined. Strictly the name should only be used for that part of the Nile valley where the Nubian language is spoken today – that is from slightly north of the first cataract at Kom Ombo in Egypt to the small town of Debba lying between the third and fourth cataracts in the Sudan. Much of this area is now uninhabited as a result of the vast inundation forming Lake Nubia, its Sudan name, or Lake Nasser as it is called in Egypt, caused by the building of the various dams at Aswan, culminating in the High Dam completed in 1969, which finally drowned a beautiful and historic land which had formed part of Nubia for millennia. The name Nubia has been used in a much wider sense when dealing with the past and sometimes it has been used as almost coterminous with the ‘Ancient Sudan’, the area of the present Republic of the Sudan. This in no way implies that all the inhabitants were speakers of the Nubian language even though the term Nubian is frequently, if inaccurately, used for the inhabitants.

In this book Nubia is used to mean not only the part which is linguistically Nubian today but to include the Nile valley to the junction of the Blue and White Niles at Khartoum and for some 250 kilometres further up the Blue Nile to include both banks of the river as far as Sennar, the southern limit of Nubian civilization as far as is now known.

The origin of the term Nubia is not known for certain. The similarity of the word with Nuba occurs, as will be seen, in various ancient writings, and the Nobatae are known from the fifth and sixth centuries AD and later, suggesting a connection. Confusion is often caused by the use of the word Nuba (not Nubian) for the people of the hills which lie to the west of the Blue Nile at approximately 30° east and 11° 30’ north. The confusion is further compounded since some of the several languages in this area are related to the Nubian spoken along the river in the more narrowly defined Nubia of today. It has been suggested that the name comes from the ancient Egyptian word nbw, meaning gold, since the area was an important source of gold in Pharaonic times and later, but it is not the name the ancient Egyptians used for the country and the suggestion may be fanciful. The Egyptians frequently called the area Ta-sety,‘Land of the Bow’, or Kush, probably a name used by the inhabitants themselves. Nubians today tend to call themselves by terms which indicate the different dialects spoken – Kenuz, Mahas, Danagla – rather than to use Nubian as a general term, except when speaking in foreign languages, but the term Nobiin is increasingly being used to designate those who speak Mahas and other very closely related dialects.

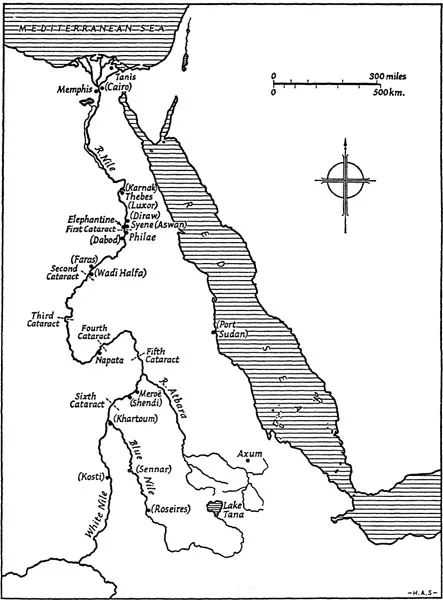

Map 1. Nubia in relation to the whole Nile valley

The country itself is largely confined to the strip of cultivated land bounded by desert which borders the river, usually rainless in its northern part, but extending beyond the river banks once south of 17° 50’ north, where annual rain can be expected and where signs of ancient human habitation are to be found at a considerable distance from the river. It must be understood that a description of the region reflects its appearance before the wholesale flooding after completion of the High Dam, since this can be described from living memory, but it should be noted that the original appearance of the country as known to those early inhabitants who are the subject of this book had already been changed by the building of the first dam in 1898–1902 and its subsequent heightenings in 1908–10 and 1929. The original landscape can only be restored for early prehistoric times by study of the geology and geomorphology, and for subsequent periods by the use of archaeological evidence and the descriptions and illustrations of early, mainly nineteenth-century, travellers.

The river, the dominant feature of the Nubian landscape, flows through a flat plain for over 2,000 kilometres from Sennar to Aswan, dropping less than 400 metres in the whole of that long journey. During the course of this journey, mostly through a valley cut through Nubian sandstone, the river flow is interrupted at six distinct places where igneous rocks of the basement complex have caused cataracts to form, from the first immediately up stream from Aswan to the sixth which is about 75 kilometres downstream from Khartoum. These cataracts have been a serious obstacle to river traffic and though boats can pass through them, with difficulty and danger, at the time of the annual Nile flood, as was done by the British and Egyptian troops during the military campaigns of 1885 and 1898, they have been a barrier to river traffic. Boats have tended only to be in general use within the various reaches of the river between the cataracts, and as a result many travellers, merchants and invaders journeyed mainly by land.

Following the course of the river Nile through the area defined here as Nubia, it starts on the Blue Nile at the modern town of Sennar (130° 34’ north 33° 35’ east) 250 kilometres up stream from its junction with the White Nile at Khartoum, from which place the single river flows over 2,000 kilometres through the Sudan and Egypt to reach the Mediterranean sea. Sennar has been chosen, as already mentioned, as the upstream boundary of Nubia since close to this town was found evidence of human occupation of Meroitic times and it is thus, until future exploration shows us more, the site of the furthest upstream dateable remains of the past. The White Nile is somewhat less known archaeologically but it is convenient to use latitude 12° 30’ north to mark the southern limits of the area to be described.

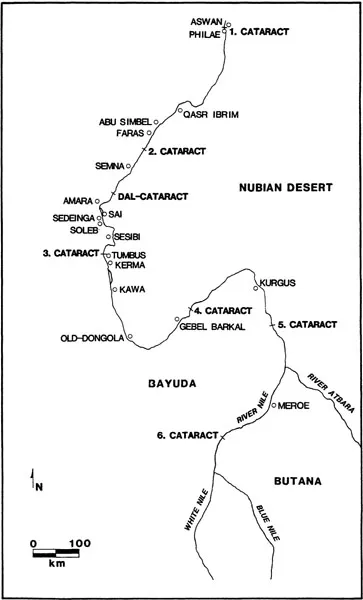

Map 2. Nubia from first cataract to junction of Blue and White Niles

The Blue and White Niles flow north past the clay plains of the Gezira (Arabic for island) which they enclose, making a rough triangle some 300 kilometres in height and with a base using the Kosti–Sennar railway line as a convenient datum, of 128 kilometres. This area and those on the east and west respectively of the two rivers consist of unconsolidated clay, silts, sand and gravels of varying depths. At its deepest it is 70 metres thick lying on Nubian sandstone. These deposits have been brought by the rivers and were probably laid down after the early Old Stone Age and certainly long before Neolithic times; radio carbon dates suggest that the deposits originated earlier than 10,000 BC.

The Blue Nile is joined by two tributaries flowing from the east, the Rahad and the Dinder, both these rivers deriving their water, as does the Blue Nile, from the summer rains of the Ethiopian plateau. In a year of plentiful rain the Dinder, especially, contributes much water to the annual flood, but in the dry season both rivers cease to flow and become a series of small ponds in a sandy bed.

The Blue Nile, arising in lake Tana in Ethiopia, is also dependent on the summer rains but its volume is far greater, and though its flow will vary from year to year there is always sufficient to provide some irrigation in the valley of the main Nile and, until the change in the flow pattern of the river caused by the building of dams from the late nineteenth century, it deposited fresh silt along the banks of the whole valley, thus making possible the agricultural development on which the civilization of ancient Egypt and much of Nubia was based.

The area enclosed by the two Niles, the Gezira already mentioned, receives rain, though in markedly varying quantities, every year and in previous centuries was important for grain production, mainly sorghum (Arabic dura), traditionally the main food crop of the central Sudan. Since the building of a dam at Sennar completed in 1925 and the introduction of perennial irrigation cotton has become the main crop and the economy of the modern country largely depends on it.

The White Nile, which rises in the lakes of central Africa, flows through similar flat country but has no tributaries in the area we are considering. It is much wider than the Blue Nile – up to 400 metres at Kosti and nearly 1 kilometre just before it reaches Khartoum, before the building of a dam at Gebel Auliya which has somewhat restricted it. This river carries less water than the Blue Nile, its flow is not so strong, and where the two rivers meet it is often ponded back by the stronger flow of the Blue Nile. The difference in colour of the waters of the two rivers – which gives rise to their names – can be clearly seen, the dark of the Blue Nile and the pale green of the White.

From this junction and the commencement of the main Nile a massive river runs through the country with evidence of old civilizations all along its banks. Except in the part known as the Butana, to be described later, human activity can only be traced in a narrow strip, seldom more than 2 kilometres wide, often much less. This activity was sometimes on both banks, but in some areas, where the desert has encroached and sand dunes have formed close to the river, only one bank has been exploited, though variation at different times in the past has changed the area of human occupation and agricultural activity from one bank to the other.

Eighty kilometres north of the river junction is the sixth cataract – the numbering of the cataracts is in the reverse direction to the flow of the river, the first cataract being at Aswan, the northern gate to Nubia. We shall in a more logical way describe the river in the direction in which it flows so that the sixth cataract is the first to be described. Frequently known as the Sabaloka, from a Nubian word for the drain pipes or waterspouts used to run water off the eaves of the houses, this cataract is formed of a mass of igneous rock, mainly granite and rhyolite, which has been cut through by the river to produce a dramatic gorge with rapids at the north end. The southern end of the gorge is overlooked by a hill, Gebel Rowyan, composed largely of granite and some 595 metres high, dominating the countryside.

Once past the Sabaloka the river takes a north-easterly direction and flows through the Shendi reach known from the name of the main town. This area, now the most densely inhabited part of the northern Sudan, has much rich alluvial soil making for productive agriculture on both banks of the Nile, though most settlement is on the east as it was in ancient times. The stretch of river goes as far as its junction with the river Atbara, the only tributary of the main Nile which flows from the south-east where it rises close to the Ethiopian border. It is highly seasonal and during the dry season is reduced to a series of pools.

Along this stretch of the Nile is found the one area with ancient buildings and ancient occupation at a distance from the river. It has already been said that rain falls in the area in most years, and in ancient times the vast region bounded by the Nile, the Blue Nile and the Atbara was the site of considerable activity, particularly in Meroitic times (c.750 BC-AD 350), and a number of monuments are to be found there. The region, a wide steppe-like territory with scattered acacia trees and plenty of grazing after the rains fall, has two distinct ecological zones with different names in present-day local use. Though frequently known as the Island of Meroe’ by archaeologists following ancient usage, it is more accurate to define the two zones by using the current Arabic names. The western portion where the ancient Meroitic sites are found is primarily of Nubian sandstone and is known as the Keraba, whereas the Butana, a name often applied to the whole, refers specifically to the granite-based eastern portion where monumental remains have not been found, though traces of possible nomadic occupation are known.

Not far north of the junction of the Nile and the Atbara another region of cataract and rapids is reached where the basement complex lies in the line of the flow of the river. The fifth cataract itself is a little up stream of Bauga and roughly marks the point north of which rain very seldom falls and where, as a result, the cultivation of dates seriously begins. The whole stretch of river from here to Abu Hamed and beyond is a series of rapids with the river running in a narrow channel through hard rock, with many small islands and one large one, Mograt, at the point where the river changes its flow to the south-west. On none of these is the cultivable land able to support more than a very small population though throughout there are plenty of traces of earlier occupation, mainly of medieval and later times.

The small town of Abu Hamed is at the point where the Nile turns sharply to flow south-west for some 200 kilometres. Formerly it was important as the southern end of a much used camel caravan route which came across the desert from Kalabsha in Lower Nubia, cutting off the bend of the Nile and reducing the journey to less than 500 kilometres, a considerable saving as compared with the distance by the river route. With the development of the railway as part of the Anglo-Egyptian invasion of the Sudan in 1898 a modified form of this route was developed, from Wadi Haifa to Abu Hamed and on to Khartoum. Abu Hamed, although it remained a railway junction, lost its importance as a major staging post.

From Abu Hamed downstream is a stretch of about 200 kilometres of extremely rough and desolate country where many small islands and rapids and rock formations of biotite-gneiss make river navigation virtually impossible. The cultivable land is much restricted and the population small. This area is the least known stretch of the river in the whole of Nubia and only the most preliminary archaeological survey has been carried out. Proposals for a dam at the downstream end of this stretch of river have led to discussion to plan for the organization of a full archaeological salvage project. Below the cataract the river emerges from the zone of igneous rocks to flow once more through sandstone where an occasional uneroded isolated hill is seen, of which the largest is Gebel Barkal, on the right bank close to the modern town of Karima. This highly noticeable hill was taken to be of sacred importance in pharaonic times and later, and it became a cult centre with many temples in the vicinity.

Several normally dry watercourses (Arabic wadi) join the Nile in this area. After heavy summer rains these will flow for a short time with water and the Wadi Abu Dom which drains from the Bayuda desert, the area within the bend of the river, has on occasion brought destructive floods to Merowe (not to be confused with the ancient town of Meroe), the small town which lies at its mouth.

Seventy-five kilometres down stream of the fourth cataract, near the town of Korti, the river turns once more to resume its northward flow, thus completing a great double bend. Flowing in the quiet stretch of the Dongola reach, named from the main town of the region, for about 400 kilometres through a region of sandstone where the right bank is heavily encroached on by sand dunes, the river traverses well cultivated alluvial plains with considerable population close to the river banks, whilst away from the river are treeless desert plains of sand and gravel. This Dongola reach flows to the third cataract where the river turns east for a short distance to traverse the biotite-gneiss rocks of the cataract. From here on date palms become common and are especially plentiful close to the cataract – this district is today the main date-producing region of the Sudan.

After the river turns north again there are large areas of alluvium on the right bank where the towns of Abri and Delgo are to be found, whilst on the opposite bank are traces of ancient occupation now largely covered with sand dunes. This stretch of river is largely unimpeded until after 200 kilometres the Dal cataract is reached, marking the southern limit of a stretch of 160 kilometres of rough water dotted with islands and igneous rock formations with one exceptionally narrow gap at Semna. This gap is about 50 metres wide and at low water the whole flow of the river passes through it. This area, known as the Batn el Hagar in Arabic or Kidin Tu in Nubian, means the ‘Belly of the Rocks’ and is an appropriate term for a region of extreme desolation with only a few small villages and tiny agricultural plots, usually irrigated by lifting water from the river by means of the ox-driven water wheel known in Arabic as saqia and in Nubian as eskalay (Plate 2). Since this device was not introduced until the last few centuries BC the earlier agricultural potential of the area must have been very limited unless there has been a considerable alteration in the river level. There is evidence for some changes in level but it does not seem that they were sufficiently great to have made a marked difference in the capacity of the area to support a large population. After 160 kilometres the second cataract proper is reached and here, close to modern Wadi Haifa, the most northerly town of the Sudan, is another major obstacle where again granite outcrops bar the free flow of the river for ab...