eBook - ePub

Readings in Music and Artificial Intelligence

Eduardo Reck Miranda, Eduardo Reck Miranda

This is a test

Compartir libro

- 308 páginas

- English

- ePUB (apto para móviles)

- Disponible en iOS y Android

eBook - ePub

Readings in Music and Artificial Intelligence

Eduardo Reck Miranda, Eduardo Reck Miranda

Detalles del libro

Vista previa del libro

Índice

Citas

Información del libro

The interplay between emotional and intellectual elements feature heavily in the research of a variety of scientific fields, including neuroscience, the cognitive sciences and artificial intelligence (AI). This collection of key introductory texts by top researchers worldwide is the first study which introduces the subject of artificial intelligence and music to beginners. Eduardo Reck Miranda received a Ph.D. in music and artificial intelligence from the University of Edinburgh, Scotland. He has published several research papers in major international journals and his compositions have been performed worldwide. Also includes 57 musical examples.

Preguntas frecuentes

¿Cómo cancelo mi suscripción?

¿Cómo descargo los libros?

Por el momento, todos nuestros libros ePub adaptables a dispositivos móviles se pueden descargar a través de la aplicación. La mayor parte de nuestros PDF también se puede descargar y ya estamos trabajando para que el resto también sea descargable. Obtén más información aquí.

¿En qué se diferencian los planes de precios?

Ambos planes te permiten acceder por completo a la biblioteca y a todas las funciones de Perlego. Las únicas diferencias son el precio y el período de suscripción: con el plan anual ahorrarás en torno a un 30 % en comparación con 12 meses de un plan mensual.

¿Qué es Perlego?

Somos un servicio de suscripción de libros de texto en línea que te permite acceder a toda una biblioteca en línea por menos de lo que cuesta un libro al mes. Con más de un millón de libros sobre más de 1000 categorías, ¡tenemos todo lo que necesitas! Obtén más información aquí.

¿Perlego ofrece la función de texto a voz?

Busca el símbolo de lectura en voz alta en tu próximo libro para ver si puedes escucharlo. La herramienta de lectura en voz alta lee el texto en voz alta por ti, resaltando el texto a medida que se lee. Puedes pausarla, acelerarla y ralentizarla. Obtén más información aquí.

¿Es Readings in Music and Artificial Intelligence un PDF/ePUB en línea?

Sí, puedes acceder a Readings in Music and Artificial Intelligence de Eduardo Reck Miranda, Eduardo Reck Miranda en formato PDF o ePUB, así como a otros libros populares de Medios de comunicación y artes escénicas y Artes escénicas. Tenemos más de un millón de libros disponibles en nuestro catálogo para que explores.

Información

1

REGARDING MUSIC, MACHINES, INTELLIGENCE AND THE BRAIN: AN INTRODUCTION TO MUSIC AND AI

The Musical Brain

From a number of plausible definitions for music, the one that frequently stands out in musicological research is the notion that music is an intellectual activity; that is, the ability to recognize patterns and imagine them modified by actions. We understand that this ability is the essence of the human mind: it requires sophisticated memory mechanisms, involving both conscious manipulations of concepts and subconscious access to millions of networked neurological bonds. In this case, it is assumed that emotional reactions to music arise from some sort of intellectual activity.

Different parts of our brain do different things in response to the stimuli we hear. Moreover, music is not detected by our ears alone; for example, music is also “heard” through the skin of our entire body (Storn, 1993). The brain’s response to external stimuli, including sound, can be measured by the activity of the neurons. Two measuring methods are commonly used: PET (Positron Emission Tomography) and ERP (Event Related Potential). PET measures the brain’s activity by scanning the flow of radioactive material previously injected into the subject’s bloodstream. Despite its efficiency, this method is rather controversial because the long term side effects of the radioactive substances to the health of the subject are not entirely known. ERP uses tiny electrodes placed in contact with the skull of a person to measure the electrical activity of the brain. As far as the health of the subject is concerned, ERP is safer than PET, but the measurement is different. Whilst PET scans give a clear cross-sectional indication of the area of the brain where the bloodflow is more intense during the hearing process, ERP gives only a voltage level vs. time graph of the electrical activity of the areas of the brain where the electrodes have been placed.

Our understanding of the behaviour of the brain when we engage in any type of musical activity (e.g., playing an instrument or simply imagining a melody) is merely the tip of an iceberg. Both measuring methods have brought to light important issues that have helped researchers uncover the tip of this iceberg. PET scans have shown that listening to music and imagining listening to music activate different parts of the brain and ERP graphs have been particularly useful to demonstrate that the brain expects sequences of stimuli that conform to established circumstances. For instance, if you hear the sentence “A musician composes the music”, the electrical activity of your brain will tend to run fairly steadily. But if you hear the sentence “A musician composes the dog”, the activity of your brain will display significant negative electrical response immediately after the word “dog”.

The human brain seems to respond similarly to musical incongruities. Such behaviour obviously depends upon one’s understanding of the overall meaning of the language in hand. A number of enthusiasts believe that we are born “programmed” to be musical, in the sense that almost no-one has difficulties in finding coherence in simple tonal melodies (Robertson, 1996).

Understanding Intelligence with AI

The understanding of the behaviour of the human brain is not, however, identical to the understanding of intelligence. Physical measurements of brain activity may certainly endorse specific theories of intelligence, but not all theories seek endorsement of this sort.

One of the goals of AI is to gain a better understanding of intelligence, but not necessarily by studying the inner functioning of the brain. The methodology of AI research is largely based upon logics, mathematical models and computer simulations of intelligent behaviour (Luger and Stubblefield, 1989).

Of the many disciplines engaged in gaining a better understanding of intelligence, AI is one of the few that has special interest in testing its hypotheses in practical day-to-day situations. The obvious practical benefit of this aspect of AI is the development of technology to make machines more intelligent; for example, thanks to AI computers can play chess and diagnose certain types of diseases extremely well.

It is generally stated that AI as such was “born” in the late 1940’s, when mathematicians began to investigate whether it would be possible to solve complex logical problems by automatically performing sequences of simple logical operations. In fact AI may be traced back far before computers were available, when mechanical devices began to perform tasks previously performed only by the human mind, including some musical tasks (Levenson, 1994).

Is intelligence synonymous to the ability to perform logical operations automatically, to play chess or to diagnose diseases? Answers to such types of questions tend to be either or ambiguous biased to particular viewpoints. The problem is that once a machine is capable of performing such types of activities, we tend to cease to consider these activities as intelligent. Intelligence will always be that unknown aspect of the human mind that has not yet been understood or simulated.

Towards Intelligent Music Machines

Music is without doubt one of the most intriguing activities of human intelligence. By studying models of this activity, researchers attempt to decipher the inner mysteries of both music and intelligence. From a pragmatic point of view, however, the ultimate goal of Music and AI research is to make computers behave like skilled musicians. Skilled musicians should be able to perform highly specialized tasks such as composition, analysis, improvisation, playing instruments, etc., but also less specialized ones such as reading a concert review in the newspaper and talking to fellow musicians. In this case the music machine would need to have some basic understanding of human social issues, such as sorrow and joy. Will computers ever display such highly sophisticated and integrated behaviour? More optimistic enthusiasts believe so (Minsky, 1985).

As happens in other areas of AI research, however, computers have so far been programmed to simulate most specialized tasks, but fairly independently from each other. Current research work is now looking for ways to integrate the ability to perform a variety of such tasks; e.g., mechanisms from systems for music analysis are aggregated to systems for composition in order to allow for the computer to autonomously compose music in the style of analysed pieces.

It is debatable whether musicians want to believe in the possibility of an almighty musical machine. Musicians will keep pushing the definition of musicality away from automatism for the same reasons that scientists keep redefining intelligence. Nevertheless, AI is helping musicians to better operate the technology available for music making and to formulate new theories of music (Balaban et al., 1992).

Formal Grammars

The notion of formal grammars is one of the most popular, but also controversial, notions that has sprung from AI research to fertilize the grounds of these flourishing new theories of music (Cope, 1991). Formal grammars appeared in the late 1950s when linguist Noam Chomsky published his revolutionary book Syntactic Structures (Chomsky, 1957). In general, Chomsky suggested that people are able to speak and understand a language mostly because they have mastered its grammar. According to Chomsky, the specification of a grammar must be based upon mathematical formalism in order to thoroughly describe its functioning; e.g, formal rules for description, generation and transformation of sentences. A grammar should then manage to characterise sentences objectively and without guesswork. Chomsky also believed that it should be possible to define a universal grammar, applicable to all languages.

The study of the relationship between spoken language and music is as old as the music of the Western culture. It is therefore not by accident that Music and AI research has been strongly influenced by linguistics and particularly by formal grammars. Many musicologists believe that Chomsky’s assumptions can be similarly applied to music (Lerdhal and Jackendoff, 1983; Cope, 1987; Holtzman, 1994). A substantial amount of work inspired by the general principles of structural description of sentences has been produced, including a variety of useful formal approaches to musical analysis; e.g., Schenkerian-like techniques (Cook, 1987; Smoliar, 1979).

A Brief Introduction to Formal Grammars

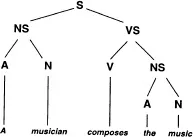

Figure 1 below illustrates an example of a grammatical rule for a simple affirmative sentence: “A musician composes the music”.

Figure 1 Example of a grammatical rule.

The rule in Figure 1 is saying that:

(a) S = NS + VS (a sentence S if formed by a noun-sentence NS and a verb-sentence VS)

(b) NS = A + N (a noun-sentence NS is formed by an article A and a noun N)

(c) VS = V + NS (a verb-sentence VS is formed by a verb V and a noun-sentence NS)

Such a rule can be programmed into a computer in order to generate sentences automatically. In this case, the computer must also be furnished with some sort of lexicon of words to choose from. For example:

A = {the, a, an}

N = {dog, compu...