![]()

II. SPECIAL PROBLEMS

FIRST GROUP: PERCEPTION

A. PERCEPTION AND ORGANIZATION

SELECTION 5

LAWS OF ORGANIZATION IN PERCEPTUAL FORMS

By MAX WERTHEIMER

“Untersuchungen zur Lehre von der Gestalt,” II, Psychol. Forsch., 1923, 4, 301–350.

301 I stand at the window and see a house, trees, sky.

Theoretically I might say there were 327 brightnesses and nuances of colour. Do I have “327”? No. I have sky, house, and trees. It is impossible to achieve “327” as such. And yet even though such droll calculation were possible—and implied, say, for the house 120, the trees 90, the sky 117—I should at least have this arrangement and division of the total, and not, say, 127 and 100 and 100; or 150 and 177.

The concrete division which I see is not determined by some arbitrary mode of organization lying solely within my own pleasure; instead I see the arrangement and division which is given there before me. And what a remarkable process it is when some other mode of apprehension does succeed ! I gaze for a long time from my window, adopt after some effort the most unreal attitude possible. And I discover that part of a window sash and part of a bare branch together compose an N.

Or, I look at a picture. Two faces cheek to cheek. I see one (with its, if you will, “57” brightnesses) and the other (“49” brightnesses). I do not see an arrangement of 66 plus 40 nor of 6 plus 100. There have been theories which would require that I see “106”. In reality I see two faces !

Or, I hear a melody (17 tones) with its accompaniment (32 tones). I hear the melody and accompaniment, not simply “49”—and certainly not 20 plus 29. And the same is true even in cases where there is no stimulus continuum. I hear the melody and its accompaniment even when they are played by an old-fashioned 302 clock where each tone is separate from the others. Or, one sees a series of discontinuous dots upon a homogeneous ground not as a sum of dots, but as figures. Even though there may here be a greater latitude of possible arrangements, the dots usually combine in some “spontaneous”, “natural” articulation—and any other arrangement, even if it can be achieved, is artificial and difficult to maintain.

When we are presented with a number of stimuli we do not as a rule experience “a number” of individual things, this one and that and that. Instead larger wholes separated from and related to one another are given in experience; their arrangement and division are concrete and definite.

Do such arrangements and divisions follow definite principles? When the stimuli abcde appear together what are the principles according to which abc/de and not ab/cde is experienced? It is the purpose of this paper to examine this problem, and we shall therefore begin with cases of discontinuous stimulus constellations.

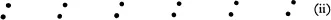

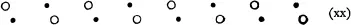

304 I. A row of dots is presented upon a homogeneous ground. The alternate intervals are 3 mm. and 12 mm.

Normally this row will be seen as ab/cd, not as a/bc/de. As a matter of fact it is for most people impossible to see the whole series simultaneously in the latter grouping.

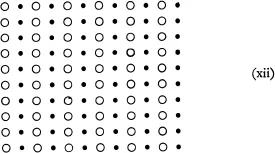

We are interested here in what is actually seen. The following will make this clear. One sees a row of groups obliquely tilted from lower left to upper right (ab/cd/ef). The arrangement a/bc/de 305 is extremely difficult to achieve. Even when it can be seen, such an arrangement is far less certain than the other and is quite likely to be upset by eye-movements or variations of attention.

This is even more clear in (iii).

Quite obviously the arrangement abc/def/ghi is greatly superior to ceg/fhj/ikm.

Another, still clearer example of spontaneous arrangement is that given in (iv). The natural grouping is, of course, a/bcd/efghi, etc.

Resembling (i) but still more compelling is the row of three-dot groupings given in (v). One sees abc/def, and not some other (theoretically possible) arrangement.

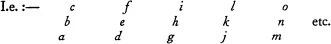

306 Another example of seeing what the objective arrangement dictates is contained in (vi) for vertical, and in (vii) for horizontal groupings.

In all the foregoing cases we have used a relatively large number of dots for each figure. Using fewer we find that the arrangement is not so imperatively dictated as before, and reversing the more obvious grouping is comparatively easy. Examples: (viii)–(x).

307 It would be false to assume that (viii)–(x) lend themselves more readily to reversal because fewer stimulus points (dots) are involved. Such incorrect reasoning would be based upon the proposition: “The more dots, the more difficult it will be to unite them into groups.” Actually it is only the unnatural, artificial arrangement which is rendered more difficult by a larger number of points. The natural grouping (cf., e.g., (i), (ii), etc.) is not at all impeded by increasing the number of dots. It never occurs, for example, that with a long row of such dots the process of “uniting” them into pairs is abandoned and individual points seen instead. It is not true that fewer stimulus points “obviously” yield simpler, surer, more elementary results.

308 In each of the above cases that form of grouping is most natural which involves the smallest interval. They all show, that is to say, the predominant influence of what we may call The Factor of Proximity. Here is the first of the principles which we undertook to discover. That the principle holds also for auditory organization can readily be seen by substituting tap-tap, pause, tap-tap, pause, etc. for (i), and so on for the others.

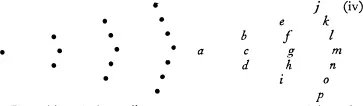

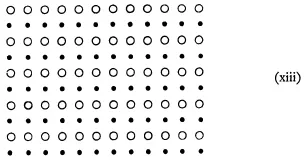

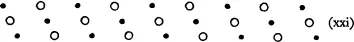

II. Proximity is not, however, the only factor involved in natural groupings. This is apparent from the following examples. We shall maintain an identical proximity throughout but vary the colour of the dots themselves:—

309 Or, again:—

Or, to repeat (v) but with uniform proximity:—

Thus we are led to the discovery of a second principle—viz. the tendency of like parts to band together—which we may call The Factor of Similarity. And again it should be remarked that this principle applies also to auditory experience. Maintaining a constant interval, the beats may be soft and loud (analogous to (xi)) thus: ..!!..!! etc. Even when the attempt to hear some other arrangement succeeds, this cannot be maintained for long. The natural grouping soon returns as an overpowering “upset” of the artificial arrangement.

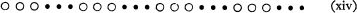

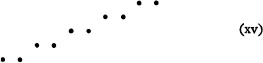

310 In (xi)–(xiv) there is, however, the possibility of another arrangement which should not be overlooked. We have treated these sequences in terms of a constant direction from left to right. But it is also true that a continual change of direction is taking place between the groups themselves: viz. the transition from group one to group two (soft-to-loud), the transition from group two to group three (loud-to-soft), and so on. This naturally involves a special factor. To retain a constant direction it would be necessary to make each succeeding pair louder than the last. Schematically this can be represented as:—

Or, in the same way:—

This retention of constant direction could also be demonstrated with achromatic colours (green background) thus: white, light 311 grey, medium grey, dark grey, black. A musical reproduction of (xv) would be

C,

C,

E,

E,

,

,

A,

A,

C,

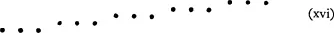

C, …; and similarly for (xvi):

C,

C,

C,

E,

E,

E,

,

,

A,

A,

A,

C,

C,

C, ….

Thus far we have dealt merely with a special case of the general law. Not only similarity and dissimilarity, but

more and less dissimilarity operate to determine experienced arrangement. With tones, for example,

C,

,

E,

F,

,

A,

C,

… will be heard in the grouping

ab/cd … and

C,

,

D,

E,

F,

,

,

A,

,

C,

,

D … in the grouping

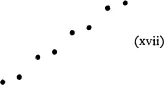

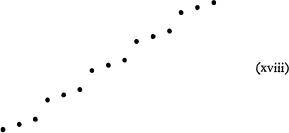

abc/def … Or, again using achromatic colours, we might present these same relationships in the manner suggested (schematically) by (xvii) and (xviii).

(It is apparent from the foregoing that quantitative comparisons can be made regarding the application of the same laws in regions—form, colour, sound—heretofore treated as psychologically separate and heterogeneous.)

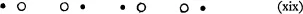

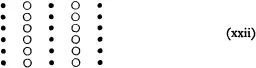

III. What will happen when two such factors appear in the same constellation? They may be made to co-operate; or, they can be set in opposition—as, for example, when one operates to favour ab/cd while the other favours /bc/de. By appropriate variations, 312 either factor may be weakened or strengthened. As an example, consider this arrangement:—

where both similarity and proximity are employed. An illustration 313 of opposition in which similarity is victorious despite the preferential status given to proximity is this:—

A less decided victory by similarity:—

Functioning together towards the same end, similarity and proximity greatly strengthen the prominence here of verticality:—

Where, in cases such as these, proximity is the predominant factor, a gradual increase of interval will eventually introduce a point at which similarity is predominant. In this way it is possible to test the strength of these Factors.

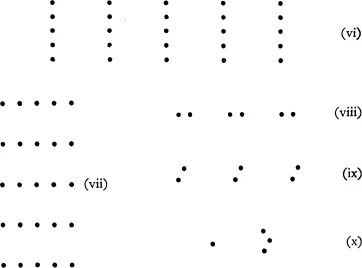

315 IV. A row of dots is presented:—

and then, without the subject’s expecting it, but before his eyes, a sudden, slight shift upward is given, say, to d, e, f or to d, e, f and j, k, l together. This shift is “pro-structural”, since it involves an entire group of naturally related dots. A shift upward of, say, c, d, e or of C, d, e and i, j, k would be “contra-structural” because the common fate (i.e. the shift) to which these dots ar...