eBook - ePub

Chaucer and the Jews

Sheila Delany, Sheila Delany

This is a test

Compartir libro

- 272 páginas

- English

- ePUB (apto para móviles)

- Disponible en iOS y Android

eBook - ePub

Chaucer and the Jews

Sheila Delany, Sheila Delany

Detalles del libro

Vista previa del libro

Índice

Citas

Información del libro

This edited collection explores the importance of the Jews in the English Christian imagination of the 14th and 15th centuries - long after their expulsion from Britain in 1290.

Preguntas frecuentes

¿Cómo cancelo mi suscripción?

¿Cómo descargo los libros?

Por el momento, todos nuestros libros ePub adaptables a dispositivos móviles se pueden descargar a través de la aplicación. La mayor parte de nuestros PDF también se puede descargar y ya estamos trabajando para que el resto también sea descargable. Obtén más información aquí.

¿En qué se diferencian los planes de precios?

Ambos planes te permiten acceder por completo a la biblioteca y a todas las funciones de Perlego. Las únicas diferencias son el precio y el período de suscripción: con el plan anual ahorrarás en torno a un 30 % en comparación con 12 meses de un plan mensual.

¿Qué es Perlego?

Somos un servicio de suscripción de libros de texto en línea que te permite acceder a toda una biblioteca en línea por menos de lo que cuesta un libro al mes. Con más de un millón de libros sobre más de 1000 categorías, ¡tenemos todo lo que necesitas! Obtén más información aquí.

¿Perlego ofrece la función de texto a voz?

Busca el símbolo de lectura en voz alta en tu próximo libro para ver si puedes escucharlo. La herramienta de lectura en voz alta lee el texto en voz alta por ti, resaltando el texto a medida que se lee. Puedes pausarla, acelerarla y ralentizarla. Obtén más información aquí.

¿Es Chaucer and the Jews un PDF/ePUB en línea?

Sí, puedes acceder a Chaucer and the Jews de Sheila Delany, Sheila Delany en formato PDF o ePUB, así como a otros libros populares de Littérature y Critique littéraire. Tenemos más de un millón de libros disponibles en nuestro catálogo para que explores.

Información

PART I

Chaucer Texts

1

The Jewish Mother-in-Law

Synagoga and the Man of Law's Tale

I. The Synagogue as Mother-in-Law

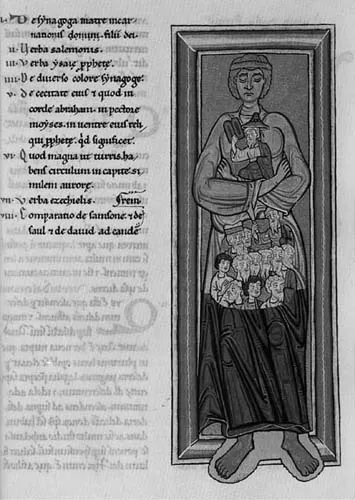

Hildegard of Bingen's fifth vision personifies the people of the covenant in the form of a woman, Synagoga (see fig. 1), who is “mother of the incarnation” and thus the mother-in-law of the Christian Church, Ecclesia, who is the bride (sponsa) of Christ. Hildegard adopts the terms of Biblical exegesis of the Song of Solomon along with medieval iconography in which the two female figures are rivals: Synagoga because of her unbelief, and supplanted in favor of Ecclesia. She begins with what she sees:

After this, I saw the image of a woman, pale from her head to her navel and black from her navel to her feet; her feet were red and around her feet was a cloud of purest whiteness. She had no eyes, and had put her hands in her armpits; she stood next to the altar that is before the eyes of God, but she did not touch it. And in her heart stood Abraham, and in her breast Moses, and in her womb the rest of the prophets, each displaying his symbols and admiring the beauty of the Church. She was of great size, like the tower of a city, and had on her head a circlet like the dawn.1

Next Hildegard tells us what she hears:

And again I heard the voice from Heaven saying to me: “On the people of the Old Testament God placed the austerity of the Law in enjoining circumcision on Abraham; which He then turned into sweet Grace when He gave His Son to those who believed in the truth of the Gospel, and anointed with the oil of mercy those who had been wounded by the yoke of the Law.

Last comes Hildegard's interpretation of her vision:

Figure 1. Synagoga. Hildegard of Bingen's Scivias 1.4; southern Germany, c. 1165. Formerly Wiesbaden, Hessiche Landesbibliothek MS. Cod. minor Hildegardis, folio 35, recto. Present whereabouts unknown. Permission to reproduce image from facsimile courtesy of Brepols Publishing.

Therefore you see the image of a woman…. She is the synagogue, which is the mother of the Incarnation of the Son of God. From the time her children began to be born until their full strength she foresaw in the shadows the secrets of God, but did not fully reveal them. For she was not the glowing dawn who speaks openly [i.e., Ecclesia], but gazed on the latter from afar with great admiration and alluded to her thus in the Song of Songs: … Who is this who comes up from the desert, flowing with delights and leaning upon her beloved [Song of Solomon 3:6, 8:5] …

Hildegard goes on to explain that Synagoga, deserted by God in favor of Ecclesia, “lies in vice” (134). The parti-colored figure of Synagoga is pale above, but “black from her navel to her feet,” which are red for she is “soiled by deviation from the Law and by transgressions of the heritage of her fathers … for she disregarded the divine precepts in many ways and followed the pleasures of the flesh” (134) and waded in the blood of Christ.

Still, despite these negative features, the outcome Hildegard foresaw for Synagoga was ultimately positive, representing an early position in the evolving Jewish-Christian polemic: “So too the Synagogue, stirred up by Divine clemency, will before the last day abandon her unbelief and truly attain the knowledge of God.” Far from being everlastingly condemned for her unbelief, Synagoga will in the final days be enfolded into the Church of Christ: “Here the old precepts have not passed away but are transformed into better ones” (135). Hildegard's vision of Synagoga “stresses the saving interrelationships” between the Church and the community of the Jews, and represents a dignified, if melancholy, Synagoga, her body enfolding the Old Testament prophets, relinquishing her sway to Ecclesia. Eckert suggests that from this meditation it is evident that Hildegard recognized “the intrinsic solidarity of Church and Synagogue; she knew of the ultimate gift of salvation for all Israel” and thus reflected, or even surpassed in forbearance, the twelfth-century attitude of relative tolerance for contemporary Jewry.2

Hildegard's vision and its accompanying explanation have their roots in traditional exegetical and typological commentaries on the Song of Solomon, which figure the Church as the Bride of Christ. Such readings were “universally familiar” by the twelfth century.3 Imagistically, in medieval art the Synagogue's literalistic interpretation of Hebrew Scripture was often represented as darkness or the moon's half-light, while the Church corresponded to the light of the fulfillment of the prophecies and the sun's radiance.4 I want to suggest here that Hildegard's ambivalent representation of Synagoga—blind and vicious, the murderer of Christ, yet simultaneously the genesis and pre-figuration of the new Church, in fact the agent of its transformation—might profitably be seen as part of the complex code underlying two episodes in Chaucer's Man of Law's Tale. There, two wicked and non-Christian mothers-in-law of the heroine, Custance, interfere with her marriage to their sons, banish her from their realms, and, most importantly, try to prevent her from procreating and thus usurping their rule and the rule of their religions. Chaucer's depiction of the evil mothers-in-law evokes the longstanding tradition of the supplanted rule of the Old Law by the New; the mother replaced by her son's new bride.

What I will attempt to set forth here, using Hildegard's vision as my touchstone (but with no suggestion of direct influence on Chaucer), is a notion of the cultural matrix into which we might place Chaucer's rendition of this tale and our reading of it. The tale of the Man of Law, when coupled with some exploration of its sources, gestures towards an identification of the evil pagan mothers-in-law with Jewry and the allegorical figure of Synagoga. Further, I would argue that the method by which Chaucer composes his tale, selects his source material, and adds some original touches, highlights the association of the repudiated and vicious mothers-in-law with the feminized, marginalized Synagoga of an entire medieval iconographic and intellectual tradition of opposition between Synagoga and Ecclesia. Thus, what has generally been recognized by critics of the tale as Custance's poetic opposition to the pagan and demonized feminine Eastern/Muslim Other, should be extended to include her opposition to that equally threatening Other, the Synagogue. I hope to show that Chaucer's two mothers-in-law are not merely Orientalized villains, but are depicted in such a way as to render them reminiscent of Synagoga, with her traditional opponent, Ecclesia, represented by the tale's heroine, Custance. Chaucer's allegorizing, furthermore, is not purely exegetical, but informed by historically current constructs. It is my contention that this tradition of disputatio, of Jewish-Christian polemic about the place of Synagoga, was central to a medieval visual semiotics, which as literary critics we have ignored. The powerful impact of such images enables Chaucer's tale to work on levels we have hitherto left unexplored.

At its thematic heart, the tale of the Man of Law is about families and pedigree. Custance, Christian daughter of the Roman Emperor, becomes a mother through her second husband Alla of Northumberland, who has converted to Christianity; her son, Maurice, returns with his mother to Rome from England and by dynastic right becomes the next Roman Emperor. Carolyn Dinshaw has demonstrated that the narrator Chaucer assigns to the tale, the Man of Law, is adept at family law, including “marriage gift, legitimacy of offspring, rules of descent, the establishment of the household, and succession to property.”5 So it comes as no surprise that family, in this tale, forms a locus of anxiety. Dinshaw elegantly argues that the lawyer tells a tale which represses the story of incest and gender asymmetry which the patriarchal code within the tale must not articulate. I would add to Dinshaw's analysis of familial dynamics the notion that in a large sense the tale demonstrates a kind of Oedipal hostility towards the mother (Synagogue, orientalized as Other) and old ways of matriarchy, turning to embrace the patriarchy which in the tale is aligned with (despite the feminine noun) Ecclesia.6 The tale might also be construed as a repudiation of sinful mother Eve in favor of her redeemed descendant, the Virgin Mary,7 for the mothers-in-law do in fact become poetically associated with Eve in the tale, as Custance does with the Virgin. The endogamy which the evil mothers-in-law wish for their sons is replaced by the exogamy of their marriages to Custance, marriages which doom the pedigree of those pagan empires and their religions. Likewise, exhortation to endogamy is a marked feature of many Old Testament books; exogamy and proselytizing a feature of the New. Christianity's descendants, as well as its ancestors, are depicted in the families at the center of The Man of Law's Tale. I propose that Chaucer's poem can be seen to allude to, although it does not name, the central mother-in-law/daughter-in-law conflict perceived by the Middle Ages: that between Synagoga and Ecclesia.

In medieval law and medieval imagination, the Jew and the Muslim “were inextricably linked together in the consciousness of Christians.”8 The two idolatrous creeds were conflated in the object of the Crusades—the retrieval of the Holy Land—and the xenophobia of the Crusaders was directed at the undifferentiated infidel who hindered that quest. If we attempt a cultural reading of The Man of Law's Tale—one which considers art-historical monu-ments and which historicizes images—we find that the Jewish Other irrupts from its repression in the text, through its abundant availability in the medieval context of art, history, and theological debate. This repression is symptomatic of the Jew as the essential Other to the medieval Christian West, despite their textual absence from the tale, and indeed their physical absence from England.

What kind of cultural work such a tale might perform, and why Chaucer's version identifies the pagan women with Synagoga more specifically than does his immediate source in Trevet,9 are topics worth pondering. In her work on anti-Semitism in The Prioress's Tale, Louise O. Fradenburg sees representations of the Other as revealing an important perspective on Western Christian self-representations. Fradenburg maintains that The Prioress's Tale is shaped by the fear of being cut off from language and community.10 Such concerns permeate The Man of Law's Tale as well, where the mothers-in-law, who fear for their communities, are silenced. Bereft of her community early on and sent off by her parents to appease political exigencies, Custance journeys through the tale generally silent except to pray, and at several points (1. 525, ff., 981–82) even refusing to speak to reveal her own identity. The narrator's voice—that of the Man of Law—dominates and bloviates as the victorious Christian voice, refusing to validate the consciousness of those who are outside the community. As both Fradenburg and Susan Schibanoff contend, this silencing of the evil Other serves to strengthen social structures against a common enemy. Sheila Delany, noting the Orientalism in Chaucer's Legend of Good Women, suggests that anxiety about Ottoman expansion in the fourteenth century, fueled by threats and actual confrontations in the 1390s, would have been of real concern to an English diplomat like Chaucer, and thus sees nothing untypical in the pervasive use of the essentialized Oriental Other in Chaucer's work.11 Still, no one has yet recognized the conventional anti-Semitic elements in The Man Of Law's Tale, veiled and muddled as they are with the generalized pagan and Saracen threat. It is conceivable that anxie...