![]()

Part 1

‘Entrepreneurial’ informality? Self- and off-the-books employment

![]()

The case of Sasha and Natasha

Colin C. Williams and Olga Onoschenko

Introduction

Every society has to produce, distribute and allocate the goods and services its citizens require. All societies, in consequence, have an economy of some type. Economies, however, can be organized in various ways. To depict how an economy is structured, three modes of delivering goods and services have been commonly differentiated, namely the ‘market’ (private sector), the ‘state’ (public sector) and the ‘community’ (informal or third) sector (Giddens 1998; Gough 2000; Polanyi 1944; Thompson et al. 1991), even if different labels are sometimes attached to these realms. Based on this tripartite depiction of economies, a widespread consensus exists regarding the trajectory of economic development in post-Soviet spaces. First, it is believed that goods and services are being increasingly produced and delivered through the formal (market and state) economy rather than through the community or informal sphere (i.e., known as the ‘formalization’ thesis) and, second, that this formal production and delivery of goods and services is increasingly occurring through the market sector, known as the ‘marketization’ thesis.

To start to examine this, this chapter examines the lives of Sasha and Natasha. If this transition towards the formal market economy is going to be seen anywhere, it will find expression in this couple. Both have formal jobs as doctors in the Ukrainian health service and, as a dual-career family, should be deeply embedded in the formal market system, earning income which they then use to purchase the goods and services they need. As this chapter will show, however, once one scratches the surface of this composite family's daily life and begins to unravel the livelihood practices they pursue in order to both get-by and get-ahead, one starts to recognize that the transition to the formal market economy is much shallower than at first thought and that they engage in a diversity of economic practices, of which work in the formal market economy is just one amongst many.

To show this, therefore, this chapter is structured as follows. In the first section, we will evaluate critically the shortcomings of the conventional dual economies depiction of economies and, following this, the second section will present a conceptual framework to capture the multifarious economic practices in post-Soviet spaces, namely the ‘total social organization of labour’ (TSOL) approach. Following this, the third section will then examine the livelihood practices pursued by Sasha and Natasha through this lens, examining the plurality of labour practices that they employ to secure their livelihood. The outcome will be a mapping of the diversity of economic practices that this family uses to secure a livelihood in contemporary Ukraine so as to demonstrate the shallow permeation of the formal market economy and the persistence of diverse economic practices in contemporary Ukraine so as to open up the future to other possibilities than the hegemony of the formal market economy.

Blurring the formal/informal economy dichotomy: from dual to diverse economies

The starting point of this chapter is a recognition that the depiction of the formal economy as strong, extensive and growing, and the discrete and different informal economy as weak, marginal and declining, exemplifies what Derrida (1967) terms a hierarchical binary mode of thought. This formal/informal economy dualism, that is, is first of all grounded in a conceptualization of two opposing economies which are stable, bounded and constituted via negation and, secondly, the resultant separate economies are read hierarchically in a manner that bestows the superordinate (the formal economy) with positive attributes and as growing, whilst the subordinate or subservient ‘other’ (the informal economy) is endowed with negativity and as dwindling. The outcome is twofold. On the one hand, a relationship of opposition and exclusion is established between the two realms, rather than a representation of similarity and mixture. On the other hand, the resultant dichotomy becomes imbued with a normative discourse of ‘progress’ in which the extensive superordinate ‘us’ (the formal economy) becomes privileged over the separate, much weaker and residual subordinate ‘other’ (the informal economy). As Latouche (1993) recognizes, the informal economy becomes represented as primitive, stagnant, marginal, residual, weak, existing only in the margins and scattered across the economic landscape, whilst the separate and distinct formal economy is constructed as systematic, naturally expansive and extensive.

Since the turn of the millennium, however, a small stream of thought has emerged composed of a loose coupling of an array of post-structuralist, post-development, postcolonial and critical scholars, or what Gibson-Graham (2008), who are two authors writing as one, have termed a ‘diverse economies’ school of thought. This has begun to contest not only this hierarchical binary reading of the formal and informal economies as separate hostile spheres but also the privileging of the formal over the informal (e.g. Chowdhury 2007; Escobar 2001; Gibson-Graham 1996, 2006, 2008; Gibson-Graham and Ruccio 2001; Latouche 1993; Leyshon 2005; Smith and Stenning 2006; Williams 2002, 2003, 2004, 2005, 2006, 2009; Williams and Round 2007). The aim in doing this has been to try to recover recognition and re-valuing of the plethora of economic practices in contemporary societies and to challenge the assumption that formalization and marketization are totalizing trajectories of economic development.

Livelihood practices: the ‘total social organization of labour’ approach

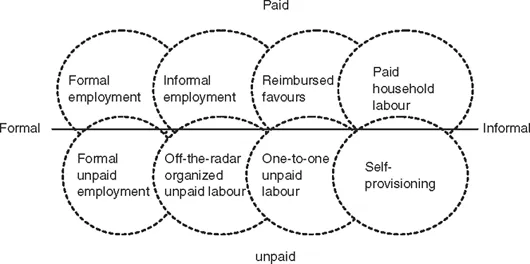

Perhaps the most prominent and promising attempt to achieve this so far is the ‘total social organization of labour’ (TSOL) approach of Glucksmann (2005: 28) who reads ‘the economy as a “multiplex” combination of modes, rather than as a dualism’. In her TSOL approach, and as Taylor (2004) displays, a spectrum of labour practices is constructed ranging from formal to informal and this spectrum is then cross-cut by whether the labour is paid or unpaid (Glucksmann 1995, 2000, 2005, 2009). Here, therefore, the intention is to use this TSOL conceptual framework in order to transcend the formal/informal economy dualism and to understand the heterogeneous labour practices in economies, but with one modification. Rather than portray labour as either paid or unpaid, a further spectrum is constructed ranging from wholly monetized, through gift-giving and in-kind labour reciprocity, to wholly non-monetized labour.

As Figure 1 displays, the result is that a seamless array of labour practices are depicted first along a spectrum from relatively formal to more informal labour practices and second, and cross-cutting this, along a further spectrum from wholly non-monetized, through gift exchange and in-kind labour, to wholly monetized labour practices. Hatched circles are deliberately employed to display how although it is possible to name various labour practices along these continua, they are all part of a borderless continua of labour practices, rather than separate kinds, which overlap and merge into one another as one moves along both the formal/ informal spectrum of the x-axis and the paid/unpaid spectrum of the y-axis. The consequence is that the borderless fluidity between different labour practices is captured and it is clearly shown how the multiple practices are not discrete but seamlessly entwined and conjoined.

In consequence, rather than adopt a simple dichotomous depiction of labour as being either formal and informal, eight broad and overlapping labour practices are identified, each possessing a range of different varieties and each merging at their borders with the various other practices surrounding them. Below, we consider the prevalence and nature of each of these economic practices by examining the coping practices employed by Sasha and Natasha in their daily lives.

Figure 1 A classificatory schema of labour practices

Livelihood practices: a case study of Sasha and Natasha

Formal employment

Formal employment refers to paid work registered by the state for tax, social security and labour law purposes. Within this formal sphere, three types of formal labour, namely in the private, public and third sectors are conventionally distinguished. However, given that private sector organizations are increasingly pursuing a triple bottom line, whilst public and third sector organizations are also pursuing profit (albeit in order to reinvest so as to achieve wider social and environmental objectives), a blurring of these three varieties of formal employment is occurring. There is also a blurring of the boundaries between formal employment and other labour practices, including formal unpaid labour and informal employment.

This can be clearly seen in the case of Sasha and Natasha. Both are doctors in the Ukrainian health service which, as Lekhan et al. (2004) point out, has undergone a radical transformation since the collapse of the Soviet Union. Sasha and Natasha are both employed full-time in the health service. Sasha is a paediatrician at a maternity hospital examining newborns and providing treatment, earning an official salary of 2,000 hryvnias ($250). Natasha, meanwhile, is an ophthalmologist and has two official part-time jobs at public outpatient hospitals where she has both priom (surgery hours) and cherguvannia (accident & emergency of hours). Both perceive their salaries as insufficient for a decent quality of life. Whilst the price of foodstuffs is relatively low mainly due to lower quality control (1 litre of milk costs approximately $1, a loaf of bread $0.8, a BigMac $2), imported consumer goods, such as clothing or cars are more expensive than in Western Europe due to import taxes. $8, a BigMac $2), imported consumer goods, such as clothing or cars are more expensive than in Western Europe due to import taxes.

In order to earn enough, Sasha and Natasha have not turned to the small but burgeoning private healthcare sector. In part, this is because doctors in the private sector receive only 10–15 per cent higher salaries compared with the public sector (Lekhan, 2010: 68). Another factor is that Sasha at least is able to work overtime. As a full-time doctor, he is employed for 40 hours per week for which he earns what he calls a ‘single rate’. However, if he works extra hours, he receives one and a half or double wage rates. Indeed, Natasha jokes:

If you work on single rate, you have nothing to eat. If you work on double rate, you have no time to eat.

At the time of the interview in 2010, Sasha was doing as much overtime as he could, not least because he had heard of forthcoming changes in the healthcare system and was fearful he might be made redundant. At the time, each health administrative area had at least one children's clinic and a separate adult clinic responsible for outpatient care, an in-patient hospital (including for emergency services), a maternity hospital and some specialized hospitals (for treatment of tuberculosis, etc.). Each healthcare area was divided into districts, with each district assigned one or two paediatricians and physicians, spending part of the day doing surgeries in policlinics and the other part of the day visiting patients at home unable to come and who ask to be seen by a doctor at home. At the time of writing, in 2012, Sasha and Natasha were perhaps right to be fearful. In 2011, it was announced that children and adult clinics would be merged, and that there would no longer be separate paediatricians and physicians in each district, but instead just one general practitioner (GP). For Sasha and Natasha, however, it was not just overtime which was important for securing a better livelihood.

Informal employment

Informal employment refers to paid activities unregistered by, or hidden from, the state for tax, social security and labour law purposes (Williams 2009). Such employment ranges from wholly undeclared employment (either as a waged worker or self-employed person) to under-declared formal employment where formal employees receive an additional undeclared wage from their formal employer alongside their formal declared wage (envelope wage) or the formal self-employed do not declare various portions of their earnings.

When asked about whether they were paid an envelope wage, Sasha and Natasha both asserted that although this practice was rife in many walks of Ukrainian life, it did not really apply to them working in the public sector healthcare system. However, they told a different story when it came to wholly undeclared employment. First of all, Sasha did not just work overtime in his formal employment to boost his wage but, more lucratively, engaged in what might be termed informal self-employment and this was currently by far the most important source of income for the household. In his formal job at the maternity hospital, he did many home visits. As he put it,

2,500 hryvnias isn't enough to survive. I have to earn money on the side. When I visited mothers and their babies at home, I started charging $5 per call out. One time the mother of one of the patients asked me, how much money she owes for a visit. I said: ‘fifty’, meaning fifty hryvnias. She brought me $50. Since then, I've raised the fee. I now charge €20 for one-off home call outs. Some clients though pay me a fixed amount per month, €100. For this, I visit the baby regularly until they are one year old and the parents can call me 24 hours seven days a week if the baby is unwell.

When asked whether he wanted to formalize this activity such as by starting up a formal private sector medical practice, he replied:

If I want to register a private medic, I would need a cabinet [doctor's consulting room]. And it is not easy to open a cabinet in our country: a lot of papers need to be signed requiring bribes to officials … You need to find a place, to get approvals from sanstanciya [the sanitation centre], oblzdravotdel [the regional healthcare department], formalize everything … this would require too much money. Being registered is just not profitable. It would mean dozens of inspectors all taking money from me.

For Sasha, therefore, there is no need to register as a private medic. Natasha, meanwhile, and in addition to her two part-time formal jobs as an ophthalmologist at public outpatient hospitals, is also an undeclared waged employee at an optician's where she conducts eye tests. When asked about this, she says

My two part-time jobs are in state hospitals. Everybody is officially registered there. As for my secondary activity — it is preferable for me not to be registered as I do not have to pay taxes. My employer is absolutely happy with this — he employs three people, but pays taxes only for one.

Together, this informal employment of Sasha and Natasha generates income worth twice as much as their formal jobs, giving them a comfortable existence.

Reimbursed favours

Reimbursed favours involve the provision of one-to-one help to either kin living outside the household, friends, neighbours or acquaintances where monetary payment is exchanged. Profit, nevertheless, is not always the primary or sole intention of the customer or the supplier. Reimbursed favours exist on a continuum ranging from those conducted for distant social relations or anonymous customers more for profit-oriented reasons to those undertaken for closer social relations where the profit-motive is largely absent and the rationales involve redistribution and consolidating social relationships, with many combinations in ...