![]()

Part I

Case studies

![]()

1 The Pont des Arts controversy

On 20 November 1996, the mayor of Kyoto, Masumoto Yorikane, called a press conference and made a surprising announcement: right in the centre of town, a footbridge would be built over the Kamogawa, the river running through Kyoto. Taking up a proposal by the visiting French president, Jacques Chirac, whom he had met at a reception in Tokyo the previous night, it would be a replica of the Pont des Arts. This Parisian footbridge spans the Seine in front of the Louvre and, true to its name, connects the famous museum with the Académie des Beaux Arts and other art institutions on the Rive Gauche. The replica would be constructed in celebration of the ‘French Year in Japan’ and the fortieth anniversary of the sister-city relationship between Paris and Kyoto, both scheduled for 1998.

The mayor certainly had no idea that his announcement would trigger the most widely fought controversy about architecture that Kyoto has seen to date. Looking back at the six years until the footbridge idea was finally laid to a provisional rest in 2002, one cannot help but marvel at the strangeness of it all, especially when comparing the modest scope of this construction project with earlier embattled ones. Marx’s dictum of history repeating itself, first as tragedy, then as farce comes to mind. For all its peculiarity, however, the unfolding of the Pont des Arts affair offers valuable insights into wider social processes, particularly those relating to citizen self-organisation, the legitimacy of imitation and the social conception of public space.

I will start my account with a chronology of events, introducing the major protagonists as I go along, before giving what I consider the causes of the bridge opponents’ unexpected victory. Finally, I will show how, in the aftermath of the plan’s withdrawal, the advisory committee set up over the question of a different footbridge in the same location brought everything back to start. Unwittingly, as it seems, this committee re-empowered wellestablished social institutions that had been superseded by new forces only temporarily.

Deconstructing a French bridge

The rise of the protest movement

Mayor Masumoto’s announcement did not come entirely out of thin air. A bridge at that site had been officially discussed already, in 1980, finding approval on the east bank of the river but strong opposition among residents and businesses on the western side. The idea resurfaced in master plans in 1987, at that time with explicit reference to a pre-war predecessor, and in 1993, now even with a set construction date. Again, however, the resistance of the western neighbours led to inaction. Now, however, the plan returned in a new garb, and that this was French couture was no accident: the sister relationship with Paris is very active, and Parisian models had also been invoked on previous occasions when discussing a (later aborted) plan to remodel the upscale Okazaki area as the ‘Montmartre’ of Kyoto, when Oike Avenue was chosen to become the ‘Champs-Elysées of Kyoto’, or all the way back in the 1960s, when Kyoto Tower was likened to the Eiffel Tower (Chapter 2). The general climate for bridges in Japan was also favourable, as several large bridges connecting major islands had just been opened with great fanfare. ‘Japan currently suffers from bridge addiction (hashi chûdoku-shô)’, as I heard a Japanese anthropologist remark.

Somewhat curiously, there was no immediate reaction to the mayor’s announcement. Instead, the City Assembly – dominated by a grand coalition around the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP; Jimintô) that also backs the mayor – allocated a budget for preparatory investigations in February 1997, and the plan was submitted to various standing advisory committees (shingikai) on town-planning matters whose legally required consent was duly given. Starting in June, city officials also held explanatory meetings (setsumeikai) with local neighbourhood representatives, in which the new bridge was presented as an accomplished fact. Gatherings of opponents, by contrast, did not occur before May 1997. Only at the end of July, when the legally prescribed public exhibition of the building proposal was announced, did a number of citizen activists draft a first petition demanding the reconsideration of the plan. Many of these were veterans from the earlier conflicts over the Kyoto Hotel, the new station complex and the development projects on Kyoto’s hills (Chapter 2).

Once the seeds of protest had been sown, however, they sprouted rapidly. Further meetings of citizens’ groups followed, and a number of business organisations on the west bank founded the first citizens’ initiative against the bridge in September. A Buddhist priest and leading activist of earlier controversies wrote a letter of concern to the French president, with whom he was personally acquainted. From September onwards, a stream of petitions and protest manifestos from all kinds of organisation followed, including not only the liberal and leftist end – such as the municipal employees’ union or Kyoto’s bar association – but also groups that had not spoken out on earlier occasions, such as associations of gastronomers and architects or spontaneously formed circles of prominent intellectuals. In October, a first demonstration was held, and an initial installment of protest signatures was handed over to municipal authorities. Late autumn saw further public meetings, panel discussions and seminars, attracting growing audiences. Additional protest groups were founded, now also on the eastern side of the Kamogawa. Citizen activists also sought contact with French authorities, writing letters of inquiry and visiting the French embassy in Tokyo.

At first, mainstream mass media reported the developments only in a matter-of-fact way. In September, however, the French daily Le Monde took up the Pont des Arts plan on its front page (10 September 1997), noting widespread misgivings with the plan in Kyoto and criticising Chirac for ignoring the local feelings. In the indirect way of reporting the headlines the city had made overseas, Kyôto Shinbun and the local pages of national dailies now entered the debate, also providing a platform for critical commentaries. News Station, a popular national TV news programme, brought a feature in October, and well-known anchorman Kume Hiroshi roundly derided the plan. Comedy programmes also started to make fun of it now.

Not all reactions to the bridge were negative. The public exhibition of the bridge plan in August and September produced a large majority of positive comments, which came as a shock to at least a part of the fledgling opposition movement (Kimura 1999: 39). Supportive articles also appeared. Further municipal and prefectural bodies gave their consent, and the Kyoto Buddhist Association – an umbrella organisation of Kyoto’s temples that had been active in earlier conflicts – signalled that it would keep out of the debate this time. Local resistance on the west bank also quietened down. So, when the first year after Masumoto’s announcement had passed, the controversy had become widely known, but nothing as yet indicated that the bridge might not be built.

Reasons for (de)construction

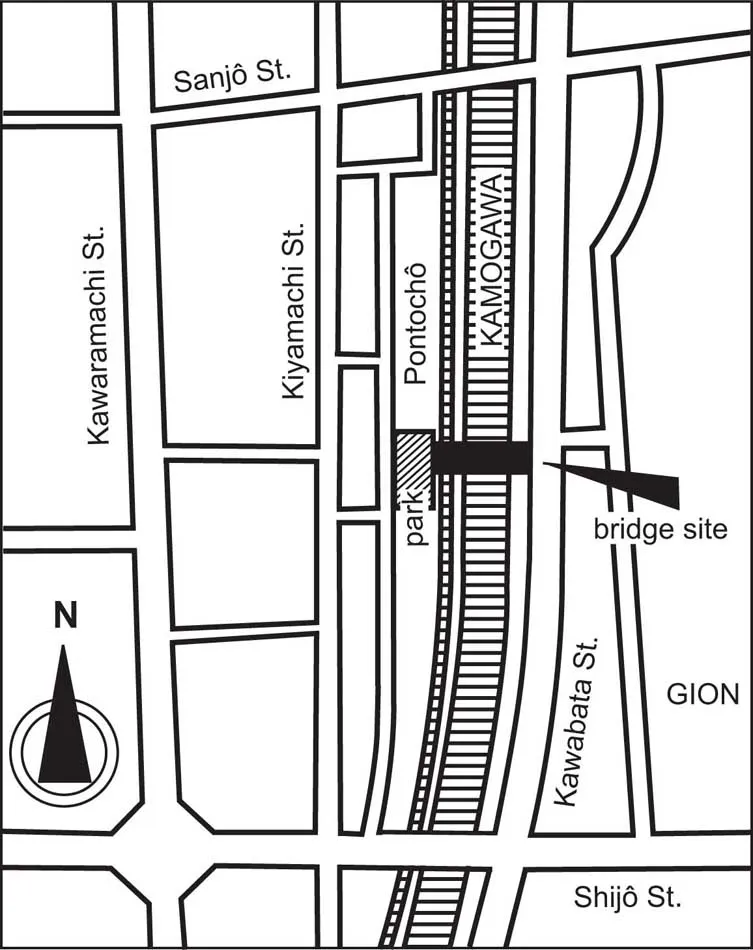

In the supporters’ eyes, there were good reasons for a bridge at the planned site. Right in the busiest part of town, it lies within a particularly long stretch of about 600 m where the river cannot be crossed. The two neighbouring bridges, Sanjô and Shijô, are often crowded, and the latter particularly offers little space for pedestrians, let alone those with prams or in wheelchairs. From the viewpoint of disaster prevention too, an additional overpass and access to the narrow alley Pontochô, which no fire engine can enter, was characterised as highly desirable (Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1 Area around proposed bridge site

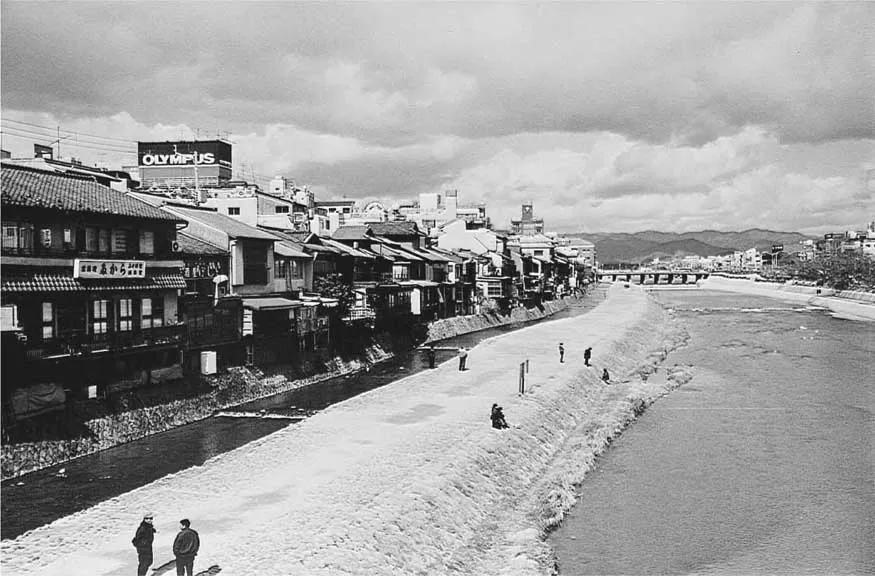

Also, a bridge reserved for pedestrians would invite a more leisurely sojourn than the other, vehicle-dominated ones. The width of the bridge was planned at a full 10 m, and, just like its model in Paris (Figure 1.2), it would be covered with wooden planks and furnished with benches and flower boxes (Figure 1.3). The vista into the Kitayama mountains framing the Kyoto basin in the north has been celebrated from ancient times, and other attractions are the old wooden facades and verandahs of the restaurants, bars and chaya (geisha-party houses) of the famous geisha quarter Pontochô (the field site for Dalby 1983). With the bridge replica realised, these scenic charms could be enjoyed from a new angle and in a more relaxed way than from the existing bridges. Easily integrated into walks through Pontochô and the other old geisha quarter, Gion, on the western side and equipped with cosmopolitan features, the bridge would also attract visitors and thereby contribute positively to Kyoto’s ailing tourist industry.

Figure 1.2 The original Pont des Arts in Paris

Figure 1.3 Model images of the Pont des Arts replica in Kyoto Reprinted with permission of Kyôto-shi Kensetsu-kyoku

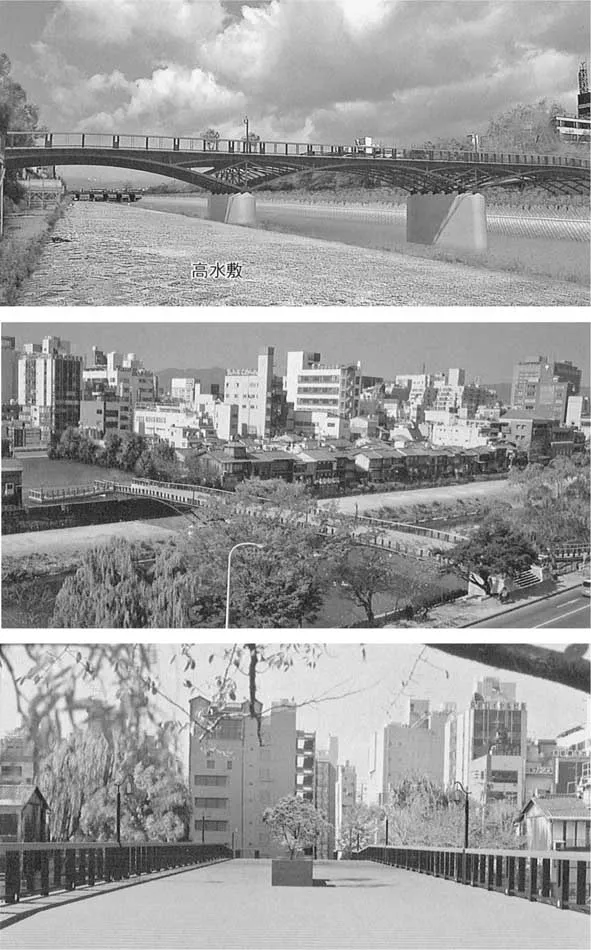

The opponents of the bridge, however, saw most of these virtues as vices. Rather than enabling the enjoyment of the scenery, the bridge would destroy the latter, cutting through a large stretch of free space that, in this reading, was an asset rather than a liability. Given that car access to the Pontochô houses is possible only via the western embankment, the walkway of the bridge would have to be higher than that of the two neighbouring bridges, allowing emergency vehicles to pass underneath. Thus, the bridge would force itself into the scenery of distant mountains and wooden facades, thereby ruining the view from Shijô bridge (Figure 1.4).

Moreover, the western approach would cut through Pontochô, effectively dividing it into two halves. This would endanger the intimate and elegant atmosphere of that famous alley, with its width of barely 2 m (Figure 1.5). It would also create a direct connection with the parallel Kiyamachi Street. There, the recent refashioning into a komyunitî dôro (‘community road’), with wider walkways and more attractive pavements and street furniture, had prompted undesirable consequences: youngsters were congregating in large numbers, especially on weekend nights, and all kinds of deviant behaviour – violent fights, street prostitution, even a case of rape – had kept the police busy. The narrowness of the present connecting walkways, which often pass through buildings, had prevented a spillover so far. Local residents and shopkeepers feared, however, that the bridge and its access would be integrated immediately into this questionable street culture and provide it with better points of entry into the geisha alley. Current customers would certainly not condone such a development, and a famous piece of Kyoto’s cultural heritage might be lost. Supporters of the bridge from the east side were accused of having precisely this in mind: envious of Pontochô’s business, they were only scheming to divert customer flows to themselves.

Figure 1.4 Kamogawa as seen from Shijô bridge (Pontochô verandahs on left side)

Figure 1.5 Pontochô

A further objection against the bridge was its effect on the waterway it spanned. Most of the year, the Kamogawa is an unimpressive river that often is only knee-deep. A few hours of heavy rain suffice to transform it into a torrential stream, however. No fewer than 249 floods are on historical record, and the last devastating inundation of 1935 immersed most of Pontochô’s houses up to the first floor. Around Shijô Avenue, the Kamogawa narrows down, its inclination decreases, and it bends westward from its straight north–south course, producing a peak in the water level (Kimura 1999: 30–1). Moreover, for a river overflowing its banks, the massive pillars of the new bridge would create an obstacle, with the additional danger of uprooted trees and debris piling up in front of them. The design of the planned bridge was another controversial point. Instead of two concrete pillars, a steel frame and European-style arches, said some opponents, a potential bridge would have to be of wood, its style Japanese (wafû) and its proportions humble, blending with the surroundings instead of standing out. A line of stepping stones – as there are many in the Kamogawa further north – might be fully sufficient.

There were also opponents who cared little about the bridge as such, but could not bring themselves to accept the political decision process. In their reading, the mayor simply monopolised a piece of public space for his private agenda and, with a single day’s deliberation, ignored all the opposition the previous bridge plans had aroused. He thus paid scant attention to the ideal of pâtonashippu (‘partnership’) that, as official communications of Kyoto City never fail to emphasise, is supposed to govern the interactions between local government and the citizens. In addition, all other administrative organs involved – the City Assembly, various advisory committees and their equivalents at the prefectural level that, having official control over all water bodies, had to consent – supported the plan and did not object to the time constraints put on them for fulfilling their prescribed control function. To many opponents, it thus seemed that, given a sufficiently powerful position, any personal whim could be realised in Kyoto, and this did not fit well with their ideal of a functioning democracy.

Most salient of all arguments in the public debate, however, was the fact that this was a foreign bridge proposed by a foreign president, and a replica in addition. At that famous site, such a structure was bound to remain an alien, all the more so as the view of mountains and the wooden houses of Pontochô are widely perceived as emblematic of Kyoto and Japan (Kimura 1999: 17). And then, in addition, a mere imitation of something existing elsewhere would be entirely inadequate for such a celebrated site, destined to become the laughing stock of visitors. If French–Japanese relations were to be furthered, an original creation would be more appropriate, or it would be better to invest the earmarked funds in exchange programmes rather than in monuments. The rather bluntly phrased ‘Gaikoku no hashi wa iranai’ (‘We don’t need a foreign bridge’) became the most prominent anti-bridge slogan, and, for many opponents, the ‘Art bridge’ (Geijutsu-bashi) or ‘Kamogawa footbridge’ (Kamogawa hodôkyô), as the replica was officially referred to, simply became the ‘French bridge’ (Furansu-bashi).

The proponents of the bridge plan tried their best to refute these arguments. Wasn’t Pontochô’s special atmosphere long gone, with the geisha business in decline and unsophisticated drinking places, souvenir shops, and oversized signage advancing? Wasn’t the bridge a more democratic way of enjoying the view, compared with the costly verandahs of the riverside restaurants? Wasn’t it strange that opponents were so sensitive to landscape damage in th...