eBook - ePub

Mourning Dress (Routledge Revivals)

A Costume and Social History

Lou Taylor

This is a test

Compartir libro

- 326 páginas

- English

- ePUB (apto para móviles)

- Disponible en iOS y Android

eBook - ePub

Mourning Dress (Routledge Revivals)

A Costume and Social History

Lou Taylor

Detalles del libro

Vista previa del libro

Índice

Citas

Información del libro

First published in 1983, Mourning Dress chronicles the development of European and American mourning dress and etiquette from the middle ages to the present day, highlighting similarities and differences in practices between the different social strata. The result is a book which is not only of major importance to students of the history of dress but also to anyone who enjoys social history.

Preguntas frecuentes

¿Cómo cancelo mi suscripción?

¿Cómo descargo los libros?

Por el momento, todos nuestros libros ePub adaptables a dispositivos móviles se pueden descargar a través de la aplicación. La mayor parte de nuestros PDF también se puede descargar y ya estamos trabajando para que el resto también sea descargable. Obtén más información aquí.

¿En qué se diferencian los planes de precios?

Ambos planes te permiten acceder por completo a la biblioteca y a todas las funciones de Perlego. Las únicas diferencias son el precio y el período de suscripción: con el plan anual ahorrarás en torno a un 30 % en comparación con 12 meses de un plan mensual.

¿Qué es Perlego?

Somos un servicio de suscripción de libros de texto en línea que te permite acceder a toda una biblioteca en línea por menos de lo que cuesta un libro al mes. Con más de un millón de libros sobre más de 1000 categorías, ¡tenemos todo lo que necesitas! Obtén más información aquí.

¿Perlego ofrece la función de texto a voz?

Busca el símbolo de lectura en voz alta en tu próximo libro para ver si puedes escucharlo. La herramienta de lectura en voz alta lee el texto en voz alta por ti, resaltando el texto a medida que se lee. Puedes pausarla, acelerarla y ralentizarla. Obtén más información aquí.

¿Es Mourning Dress (Routledge Revivals) un PDF/ePUB en línea?

Sí, puedes acceder a Mourning Dress (Routledge Revivals) de Lou Taylor en formato PDF o ePUB, así como a otros libros populares de Histoire y Histoire du monde. Tenemos más de un millón de libros disponibles en nuestro catálogo para que explores.

Información

CHAPTER ONE

The Function and Ritual of European Funerals

CLOTHES mirror every nuance of the society in which they are worn, reflecting not only an individual’s aesthetic judgement but also his or her social standing and attitudes to society. Clothes also chronicle political and artistic upheavals. The study of dress, therefore, is a key which opens the door to a deeper understanding of the developments that take place in society and its social ambitions and aspirations.

Taste in dress is controlled by many factors and its functions, in whatever type of society it is worn, are many and varied, but basically clothes have been used from the earliest times as a means of clearly defining and enforcing the class divisions in society. They provide an ideal vehicle for displaying wealth and social status and sometimes for demonstrating political and religious convictions. This still applies today when anti-fashion is high fashion and secondhand clothes are as much a status symbol for the young as haute couture clothes are for the wealthy.

Women have always been used—nearly always with their own enthusiastic agreement and support—as a means of displaying their families’ rank. The ideal occasion for such a display was, and indeed still is, at public gatherings where expensive clothes could be seen by all. Ritual functions, such as the public ceremonies to mark birth, coming-of-age, marriage and death, provide a perfect setting for just such an open demonstration. The clothes worn on each of these occasions became and to some extent still are, highly elaborate and extravagant—far beyond the bounds of necessity and frequently in defiance of sumptuary laws. Babies were christened in full-length satin robes, with yards of lace hanging down below their toes, debutantes were presented at Court in Britain with ritualised, white, trained ball dresses, complete with tulle veils and white ostrich plumes. Brides or their parents still save up for months to provide the symbolic robes, full-length veils and orange blossom they will never wear again. For mourning a vast array of special clothing developed over the centuries, to be worn by the bereaved and particularly by widows. The study of fashionable European mourning dress provides us with an extraordinarily revealing insight into the functions of dress and the social position of women.

In order to appreciate the intricacies of mourning dress and to follow its stylistic evolution, it is necessary first to examine the development of European funeral ritual, which provided the public setting in which these clothes were worn. Funerals were an ideal stage for a public display of wealth and rank. Relatives were even able to improve their standing within their community by putting on an impressive and obviously costly funeral ceremony. This aspect of the death ritual grew to overshadow all others, until vast fortunes were being spent on grave offerings, mausoleums, funeral feasts and processions at royal and aristocratic funerals—as it was in ancient China and Egypt, so it became in Renaissance Europe. The rules of funeral etiquette became more and more intricate in a deliberate attempt to outmanoeuvre those further down the social ladder who could not hope to compete with all the expense. In Britain the gradual spread of funeral and mourning rituals from royal circles to the industrial working classes took about two hundred and fifty years, starting in the late sixteenth century and reflecting exactly the changing format of society and the rising aspirations of first the middle and then the working classes.

In Europe grandiose royal funerals only became possible when the heir to the throne was publicly declared and accepted before the death of the king. Before that time disorder and confusion reigned whilst the various hopeful aspirants to the Crown sought to establish their claims. Royal authority prevailed only after the king had been consecrated and crowned. Before that could occur the main concern of the heir apparent was to collect together his supporters and

1 King Edward VII and Queen Alexandra in April 1901, three months after the death of Queen Victoria, photographed at the State Opening of Parliament. Queen Alexandra is in deepest mourning. From The Sphere, 6 April 1901.

organise his own coronation. This left little time (and little money) for the arrangement of an elaborate funeral for his predecessor. On the death of William the Conqueror in 1080 the nobles fled the Court to their estates, leaving the servants to steal the dead king’s silver. The expenses of the simple royal funeral were paid for by the generosity of Herluin, one of William’s knights.1

Once immediate succession had been established, the way was paved for grandiose burials which symbolised the power and stability of the Crown—the more extravagant the better. The example was set in France when Philippe III carried his father’s body back from the Crusades in 1270–71 for a grand formal burial.2 Royal burials in France gradually developed into highly elaborate and lavish rituals which laid the foundations of mourning etiquette in Europe.

Ancient practices, including the offering of grave goods, funeral feasts and the wearing of special mourning clothes, were preserved in European Renaissance funeral traditions and survived until the nineteenth century. The offerings of expensive goods and foods, which had previously been placed in the grave, were, by the Renaissance period divided between the church, the king’s officers and other important officials who had taken part in the funeral cortège. Spoils from the funeral ceremonies included items such as coffin palls of cloth of gold, expensive wax tapers and royal horses. Protracted and bitter arguments took place between rival claimants. In 1422 the salt-carriers of Paris who carried the coffin of Charles IV claimed the cloth of gold pall, to the annoyance of the church authorities at the Abbey of St Denis, where all royal burials in France took place.3 After the funeral of Anne of Brittany in 1514 it took six years to settle all the disputed claims.4

The ancient custom of burying or burning the dead man’s horse, to transport his soul to the spirit world, was modified and the horses were instead led in the procession. In France after a grand funeral the horses were given to the church to help maintain the Crusader States. By the fourteenth century when the Holy Land had been lost horses were classified along with the wax candles and expensive black drapery, as part of the deceased’s offering to the church. At the funeral of François I in Paris in 1547 the parade horse or cheval d’honneur was covered ‘with a black crepe cloth, covering its royal purple trappings, leaving only the eyes visible.’5 In medieval and Tudor times in England one of the late king’s chargers was ridden up the nave of Westminster Abbey at his Requiem Mass, to be given to

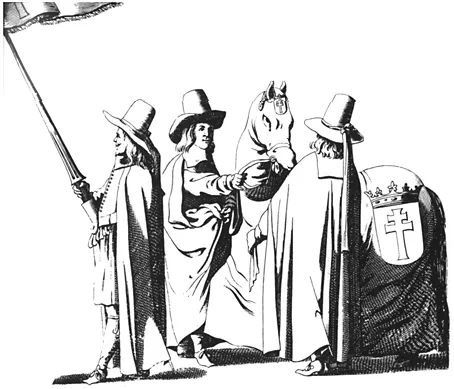

2 Riderless horse at the funeral of George II, Landgrave of Hesse, Germany, 1661. An engraving by Adrien Schoonebeek.

the church at the door of the choir. The church benefice of giving away the horse had died out in France at the end of the fourteenth century, but the tradition of the dead man’s riderless horse following the coffin has survived, particularly in Britain. The Duke of Wellington’s funeral car was followed, in his great funeral procession of 1852, by his charger, complete with the Duke’s empty, dangling boots. The most recent examples have been seen at the funerals of the Duke of Norfolk at Arundel, Sussex on 5 February 1975 and at the State funeral of Lord Mountbatten in September 1979. Both the processions were led by riderless horses, which were hung with their owners’ riding boots, reversed in the stirrups.

The procedure for royal funeral processions was laid down in France by the fifteenth century. It was carefully copied in the nineteenth century and is still maintained at royal funerals today. Everyone remotely connected with the power of the Crown took part in the parade, those nearest the coffin being the most important or chief mourners. Until the late Middle Ages the successor to the deceased always took part in royal burials, but at the death of

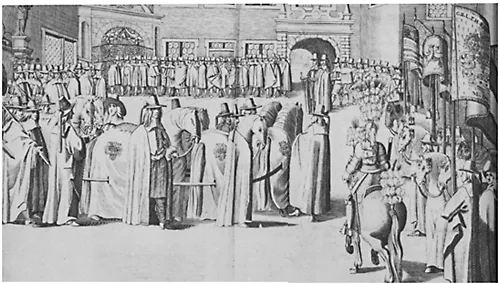

3 Funeral procession of George II, Landgrave of Hesse, Germany, July 1661, based on French medieval etiquette. Engraved by Adrien Schoonebeek.

4 Funeral procession of Queen Victoria, 1901. The streets are lined with mourners—the women in hats, the men without them. From the Ladies Field, 2 February 1901.

François I in 1547 the new heir was forbidden to attend the ceremony and the future Henri II was obliged to watch the procession from a window on the Rue St Jacques. The Procureur-Général of the French Parliament, Jacques de la Guesle, explained in 1594 that, ‘It is not fitting to their [king’s] sacred persons to associate themselves with things funereal.’6 Chief mourners at royal funerals were, therefore, not the king’s heir but other royal princes and dukes.

Women played little part in grand funerals for men, although the chief mourner at the interment of an aristocratic woman was, originally, always a woman. Queen Elizabeth I’s coffin was followed by a ma...