eBook - ePub

Migrants in Modern France

Philip E. Ogden, Paul White, Philip E. Ogden, Paul White

This is a test

Compartir libro

- 320 páginas

- English

- ePUB (apto para móviles)

- Disponible en iOS y Android

eBook - ePub

Migrants in Modern France

Philip E. Ogden, Paul White, Philip E. Ogden, Paul White

Detalles del libro

Vista previa del libro

Índice

Citas

Información del libro

A discussion of the structure and role of migration flows affecting France from 1850 to the present day. It covers both internal and international movements and consideration is given both to broad macro-scale analysis and more detailed micro-scale investigations.

Preguntas frecuentes

¿Cómo cancelo mi suscripción?

¿Cómo descargo los libros?

Por el momento, todos nuestros libros ePub adaptables a dispositivos móviles se pueden descargar a través de la aplicación. La mayor parte de nuestros PDF también se puede descargar y ya estamos trabajando para que el resto también sea descargable. Obtén más información aquí.

¿En qué se diferencian los planes de precios?

Ambos planes te permiten acceder por completo a la biblioteca y a todas las funciones de Perlego. Las únicas diferencias son el precio y el período de suscripción: con el plan anual ahorrarás en torno a un 30 % en comparación con 12 meses de un plan mensual.

¿Qué es Perlego?

Somos un servicio de suscripción de libros de texto en línea que te permite acceder a toda una biblioteca en línea por menos de lo que cuesta un libro al mes. Con más de un millón de libros sobre más de 1000 categorías, ¡tenemos todo lo que necesitas! Obtén más información aquí.

¿Perlego ofrece la función de texto a voz?

Busca el símbolo de lectura en voz alta en tu próximo libro para ver si puedes escucharlo. La herramienta de lectura en voz alta lee el texto en voz alta por ti, resaltando el texto a medida que se lee. Puedes pausarla, acelerarla y ralentizarla. Obtén más información aquí.

¿Es Migrants in Modern France un PDF/ePUB en línea?

Sí, puedes acceder a Migrants in Modern France de Philip E. Ogden, Paul White, Philip E. Ogden, Paul White en formato PDF o ePUB, así como a otros libros populares de Ciencias físicas y Geografía. Tenemos más de un millón de libros disponibles en nuestro catálogo para que explores.

Información

1 Migration in later

nineteenth- and twentieth-

century France: the social

and economic context

PHILIP E.OGDEN AND PAUL

E.WHITE

E.WHITE

1.1 The rôle of migration and mobility

Walk the streets of Paris and stop various passers-by at random. The young engineer was born in Marseille but came to Paris to train in his profession. The middle-aged woman is from Alsace and came to Paris 40 years ago to work as a domestic servant. The bar owner has lived in Paris all his life but his father came from the Auvergne. The telephonist was born in Normandy and married there but came to Paris shortly afterwards with her husband who is a surveyor. The student is from Morocco and is writing a thesis in chemistry: at weekends he works as a hotel receptionist. The street cleaner arrived 15 years ago from Mali.

The lives of all these people have been touched by the experience of migration, either their own or that of family members. This would also be largely true if a similar exercise were conducted in any small market town in France. The foreign immigrants might be less numerous, and the number of people who had themselves moved into the town might be smaller, but all would have friends and relations who had moved between different regions of France and whose experiences therefore touched the lives of the respondents.

France is, of course, not alone in the significance of migration. High levels of population movement exist in all advanced capitalist economies: such movement is itself one of the processes that has helped to establish that economic system. Current rates of internal population movement in France are similar to those experienced in the United Kingdom or Japan, although lower than mobility rates in the USA (Courgeau 1982a, p. 50). The population census of 1982 showed that, among those aged over 25 in that year, over one half were living outside the département of their birth. Over 24 million inhabitants of France in 1982 had been living in a different house or apartment in 1975 (not including those who had then been living outside France). It has been estimated that 90% of French men and women born between 1927 and 1931 were living outside their commune of birth by the time they reached the age of 45 (Courgeau 1982, p. 39).

Ministry of the Interior figures suggest that about one-third of the population of French nationality has foreign ancestry no more than three generations back, and if the population of foreign nationals is added to this group it can be seen that about 40% of the current residents of France have origins which are wholly or partly immigrant (Noiriel 1986, p. 751). Although present-day racialist sentiment tends to dwell on the low-status elements amongst this population, it is worth remembering how much has been contributed to France by individuals from this group: César Franck, Georges Simenon, Henri Troyat, Elsa Triolet, Pablo Picasso in the arts; Romy Schneider, Josephine Baker, Jane Birkin amongst cinema and popular entertainers; Marie Curie in the sciences; Le Corbusier in architecture; Manuel Castells and Claude Lévi-Strauss amongst intellectuals; Michel Poniatowski and Charles Pasqua amongst recent politicians.

Population migration has played a major rôle in shaping modern France. Indeed it is impossible to talk in terms of cause and effect here, for population migration has been part of the process by which contemporary French society has been created. It has been argued that there is a general sequence of types of mobility that a society passes through as it evolves economically: in certain respects such a sequence may parallel the familiar stages of the demographic transition model dealing with changing mortality and fertility levels (Zelinsky 1971). Certainly the universal applicability of Zelinsky’s mobility sequence can be questioned; nevertheless it is clear that, in the case of France, the transformation from an agrarian society with elements of proto-industrial activity at the start of the nineteenth century, through the burgeoning growth of urban industrial capitalism around the turn of the century, to the emerging late-capitalist society of the last years of the twentieth century has involved a series of ebbs and flows of different migration streams that have affected, at one time or another, all areas of the country and all types and conditions of people.

The period dealt with in this book starts in the middle of the nineteenth century and continues up to the present day. It should not be assumed, however, that this implies that mobility in France, in some sense, began then. Certainly the types of population movement occurring, and the numbers of people involved, increased from the mid- nineteenth century onwards, but the simple picture of French society, and even of rural peasant society, as being geographically immobile in earlier periods is to some extent a false one (Poussou 1988). Detailed studies, albeit often from fragmentary sources, have demonstrated the great range of population mobility in eighteenth- and early-nineteenth-century France (Courgeau 1982b). What changed during the nineteenth century was that the average range of geographical mobility expanded (Tilly 1979, p. 39). Discussion in the present book begins during the period when this expansion was starting to occur. In addition to the existence of mobility in France before the middle of the nineteenth century, it is also important to accept that the conditions giving rise to enhanced mobility can often be traced back to the Revolution or earlier in the emergence of proto-industrial activity, in developments in agriculture, and in patterns of political and social control (Merriman 1979). As Tilly (1979) has argued, the apparently simple concept of modernization is, in reality, far too glib for the true complexity of economic, social and demographic change in nineteenth-century France.

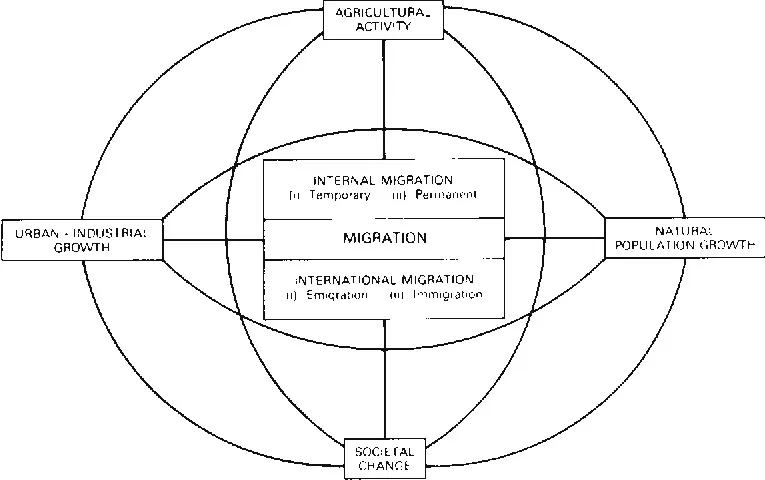

It is clear that any study of migration needs to consider the network of relationships linking population mobility with the other major dimensions of change in human activities. Figure 1.1 presents a simple version of such a model. No directional flows of influence are indicated: it is simply the possibility of connections that is the concern here. It should be noted that, although the model makes no reference to the rôle of the state, it is possible to conceptualize the whole series of inter-relationships represented as lying within an outer skin of state influence—a skin that at times has been highly permeable to international influences and at other times has been relatively more watertight.

Figure 1.1 A model of the context of migration.

The first set of relationships in the model concerns agricultural activity. This can be related to migration in a number of ways. Local mobility is an inherent part of agricultural life, for example, through marriage movements or through short-distance moves by tenant farmers (Ogden 1980, Blayo 1970, White 1982). On a larger scale the profitability of agriculture, the types of agricultural production involved (and thus the labour supply demanded) and the perceived future prospects of the sector all have implications for population movement (Winchester 1986, Béteille 1981, Collomb 1984, Vincent 1963). The types of movement involved might be extremely varied. The experience of many other European countries was that agricultural stagnation, particularly in the nineteenth century, accompanied emigration; for a variety of reasons partly related to the pace of urban-industrial growth and the pattern of natural population change, this relationship was not of great importance in France (Chevalier 1947). However, internal migration in France, both of a temporary and of a permanent nature, has often been strongly related to agriculture. Much research has been devoted to the extent, nature and results of temporary migration flows both within and from the French countryside, especially in the mid-nineteenth century when there were perhaps 800 000 seasonal migrants each year (Châtelain 1976, Corbin 1971, Carron 1965, Weber 1977, ch. 16). These flows were generally initially conditioned by seasonal labour opportunities in different agricultural systems, but increasingly the existence of urban labour demands became important. In the twentieth century, seasonal movement of immigrant labour has been initiated in the agricultural labour market (Hérin 1971).

Urban-industrial activity forms the second contextual factor in Figure 1.1. It should, however, be noted that industry has never been wholly urban in location and that nineteenth-century France was characterized by a great deal of proto-industrial activity within the countryside, often involving considerable population movements but at a relatively limited spatial scale (see Chs 5 & 7 below). Classical industrial development under the capitalist system is normally held to involve urban growth through processes of cost minimization, and the search for maximized profit through both internal and external economies of scale. Such urban growth necessitates population inflow as labour supply to the production process, while labour inflow also provides a basis for product consumption with consequent feedback effects on industrial activity, thereby generating further labour demand. Nineteenth- and twentieth-century urban growth in France occurred within a legacy of regional demographic basins that had supplied population to regional cities for many centuries. The migration patterns involved in large-scale movement in the years 1850–1914 were not therefore created ex nihilo, but related intimately to longstanding regional flows.

Urban-industrial activity may also act as a stimulus to migration in periods of declining economic output or of deindustrialization. Here migration may come into play to reduce the relative overpopulation of the affected regions. Such migration can be either international (as in emigration or the return migration of earlier immigrants) or it can involve movement wholly within the country, from depressed to growing regions. Both types of response have, at one time or another, occurred within France. For example, international migrants acted as a buffer against economic circumstances in the interwar period, entering in the period 1920–4 and leaving during the Depression years of the 1930s (Cross 1983). Since the 1970s, the counterurbanization trend in France, as elsewhere, is associated with the creation of a new spatial division of labour and with the changing relative fortunes of big cities and peri-urban areas within national economies (see Ch. 8 below).

However, the nature of agricultural activity and of urban-industrial growth or decline are not the only correlates of migration. In the French case especial emphasis must be placed on the rôle of natural population growth, because of France’s generally fragile rate of population increase over the last two centuries. In any migration model the links between natural population growth and migration are likely to be strong. In classic ideas of rural-urban migration, for example, a high rate of population growth taking place within a stagnant or slowly growing agricultural economy is sufficient to create large-scale migration movement, provided opportunities exist elsewhere to absorb the migrants. Where industrial opportunities are present within the same country then the movement will be internal, but if no such opportunities exist then overseas emigration is likely (Grigg 1980). There may be other facets to these relationships, however. For example, in periods when urban-industrial growth is rapid the existence of natural population growth is essential to assure the continued supply of labour. If such internal labour supply (possibly necessitating internal migration within the country) is not available, then immigration flows may be generated to fill the labour demand that cannot be met locally.

The final element appearing in Figure 1.1 is that of societal change. It has been usual to regard such change as being a result of migration. Population movement has been seen as part of the process whereby regional differences between ways of life in a country are reduced (Weber 1977), leading to a certain homogenization and the establishment of national societal norms. It can, however, be argued that the multifaceted character of the processes creating societal change, amongst which information flows are of obvious significance, may result in the generation of migration flows where the motive for movement is not simply economic advancement but the possibility of insertion in a new way of life. Thus, for example, movement to cities may not just have an economic character but may owe something to the perception of the wider social and leisure opportunities in the city held by residents of other areas.

Discussion of the simple contextual model of Figure 1.1 highlights the significant connections of residential mobility with other sectors of human activity. It has, however, been suggested earlier that the model must be nested within the dominant hegemonic pattern of political and thereby social control existing at a given time. Such controls themselves evolve as a concomitant part of the evolution of the capitalist system itself. State policies affecting migration are many— both direct and indirect. Direct policies may be epitomized by regulations on international migration, or measures specifically designed to create economic opportunities in specific regions or locations as a way of reducing unemployment and thereby labour outflow. Indirect effects of state policy stem from such activities as education, social welfare systems, housing intervention, economic management, and labour market controls. Prevailing political cultures may have specific views on migration. Most commonly these are likely to relate to international movement—encouraging it as a solution to problems at certain periods and rejecting it at others. Cross (1983, p. 11), for example, has argued that, in the particular conditions of French capitalist expansion around the turn of the twentieth century (with low fertility and a resistance to proletarianization amongst substantial sectors of the indigenous population): ‘Immigration served to mollify conflicts between sectors of capital, removing tensions which otherwise might have weakened the hegemony of the owning classes of France.’ Such views have, of course, been considerably modified in more recent periods (Edye 1987).

It is the task of this book to consider the structure and rôle of the migration flows affecting France over the whole period from the latter half of the nineteenth century to the present day. Discussion covers both internal and international movements. Consideration is given to both broad macroscale analysis and also to more detailed microscale investigations, but both levels can be seen as being in accordance with the overall model suggested in Figure 1.1.

1.2 Migration in France—themes and sources

For a number of reasons, the application of the general model of Figure 1.1 to the case of France yields an evolutionary scenario of great interest. France is a country for which the theoretical relationships of Figure 1.1 have been manifested in reality in sometimes extreme forms.

The most obvious of these extreme features has traditionally lain in France’s particular history of natural population evolution. Steady rates of population increase in the earlier nineteenth century were already underlain by an incipient decline in fertility, leading to the relative stagnation of France’s population in the 60 years up to World War I (Dyer 1978, van de Walle 1974), and continued low growth during the interwar period. As a result, migration in France since the middle of the nineteenth century has occurred against a background of low overall population growth rates and slow indigenous growth in labour supply (at least up until the early 1960s when the first of the larger postwar birth cohorts started to come on to the job market).

These facts have been important in limiting the extent of emigration from France and in producing the need for immigration at periods when economic growth or industrial activity has been high as, for example, after World War II.

These facts have been important in limiting the extent of emigration from France and in producing the need for immigration at periods when economic growth or industrial activity has been high as, for example, after World War II.

A second notable feature of the French scene has been the maintenance of a significant agricultural sector, at least in employment, until well into the twentieth century. Several reasons may be adduced for this fact. The history of rural French society has been marked by the establishment of a large class of small rural proprietors well before the Revolution, and the psychological ties of this class to their land helped to put a brake on the rural exodus (Noiriel 1986, p. 754). At the same time Malthusian fertility control amongst peasant families reduced the number of children who would have to migrate to seek work (Cross 1983, pp. 6–7). A further factor in the retention of agricultural population was widespread rural industrialization, giving way only late in the nineteenth century to larger-scale, urban-industrial growth (Tilly 1979). It is a paradox that, despite fears of rural depopulation and the rural exodus, the French countryside was in many ways retaining its population more effectively in the late nineteenth century than were rural areas in other north-west European states. France became an urban nation only after World War I, 70 years later than England and Wales. The links between migration and agricultural opportunities remained important in France right up to recent years, at a time when such links had been all but extinguished elsewhere in north-west Europe.

The third notable feature of the migration context of France is that of the localization of urban and industrial growth over the past century. Large-scale industrial development was, until the 1950s, concentrated in a limited number of regions—the Nord, Lorraine, Alsace (not French between 1870 and 1918 anyway), around Lyon and St Etienne, and in the great port cities of M...