![]()

1

Organicity

Of all the projects in the modernist corpus that tried to define what it meant for a work of art to be ‘organic’, to have ‘organicity’, those of the sculptor Katarzyna Kobro and the painter Władisław Strzemiński are of special importance. The terminology sounds as if it came from biology or physiology, and in one sense it did. Yet both artists meant it to evoke the very experience of the work of art in the sight and mind of a viewer. It was as if wholeness and a mutual interdependence of parts could be embodied in a modern work of art – could be what a modern work of art really was. Nothing illusionistic, therefore; no picture-making or figural building. The achievement of ‘organicity’ was for both of them to be a fifteen-year project through a maze of precedents and obstacles, images, words and things. The modern work of art was to be a model of how life – both individual and social – could be given form.

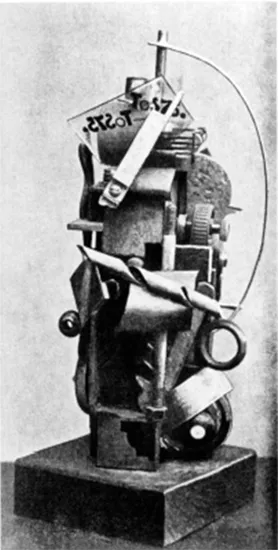

Too little is known about Kobro’s and Strzemiński’s early training for us to be entirely certain of their intellectual and artistic beginnings. Born in Moscow and Minsk respectively, both of them received artistic training in Moscow in the years 1917–19. In 1917 Kobro entered the School of Painting, Sculpture and Architecture (soon to become the Second State Free Art Studios or SVOMAS), where both Kasimir Malevich and Vladimir Tatlin were teaching, and her earliest known sculpture, an upright assembly of assorted machine parts, reflects Tatlin’s ‘culture of materials’ principles that mandated materiality – tension, density, weight and flexibility – as the proper starting-point of any contemporary construction. Strzemiński, having suffered injury, amputation and the virtual loss of one eye while serving on the Eastern Front in Byelorussia in 1916, entered the First State Free Art Studios in 1917 and also became exposed to Tatlin’s ideas. By 1920 both Kobro and Strzemiński were working as artists in the city of Smolensk in Western Russia, increasingly under the sway of Malevich’s UNOVIS (that is, Suprematist) academy in nearby Vitebsk, just across the border in Ukraine. By the end of 1921 or the beginning of 1922, the artists, now married, had crossed into newly independent Poland and had begun to establish contacts with groups in Vilnius, Cracow and eventually Warsaw. They had already begun to reflect intensively on the methods of their teachers and how to move beyond them towards a democratic modern art as well as a demonstrably ‘organic’ one.1

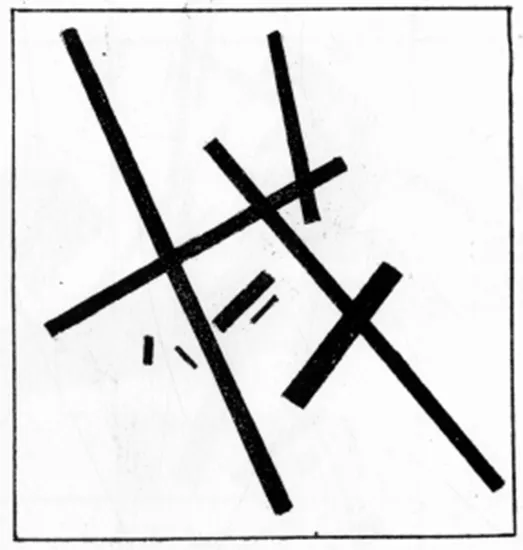

The term first enters their vocabulary in 1922. In his ‘Notes on Russian Art’, published in the journal Zwrotnica [Switch] during that year, Strzemiński’s criticisms of Malevich’s system were forthright. As he saw it, Malevich had been searching for what Strzemiński described as ‘a determinate system’, the ‘inescapable conditions from which the organicity of the work of art would follow’. He understood well that his ‘determinate system’ was in effect an evolutionary hypothesis that was embodied in a book he wrote in the early 1920s and that was being taught – there can be little doubt – to the UNOVIS students in both Smolensk and Vitebsk at that time. Its arguments echoed the theory of adaptation in Darwin’s The Origin of Species. First, says Malevich, we must read the art of painting as like a body, subject to adaptation when exposed to new conditions, but otherwise quiescent. At any given time, its norms ‘continue to exist until an additional element arises out of the various phenomena of the changing environment and causes the old norm to evolve’. Cubism’s ‘additional element’ in relation to Cézanne, Malevich says, was the ‘sickle-shape’ of straight line attached to a curve: it corresponded to the world of cranes, locomotives, iron girders and the culture of the motor car. According to Malevich, an additional element gets its strength ‘by disturbing the previous norm – if necessary by deformation – and reconstructing it’. Suprematism’s environment was flight above the earth and the view of the earth from space. Its additional element was the pictorial plane untethered from its ground. Suprematism claimed to transcend Cubism by introducing geometric planes and launching them into space. Transposed into a medical metaphor, the change to a new system is like the effect of bacteria on the human organism, such that ‘through the action of the additional element old conceptions of the conscious mind are destroyed (displaced, that is, by new conceptions)’. In this sense each norm is dynamic, and under the pressure of circumstances ‘embarks on its way to becoming a new norm, a new system’. As he further explains, ‘the Suprematist square and the forms proceeding out of it can be likened to the primitive marks of aboriginal man which represented, in their combinations, not ornament but a feeling of rhythm’.2

Fig 1.1 Katarzyna Kobro, ToS75 – Structure, wood, metal, cork, glass, c.1919, dimensions unknown, from Kompozycja przestrzeni. Obliczenia rytmu czasoprzestrzennogo [Composition of Space. Calculations of Space-Time Rhythm], Bibliokeka Grupy ‘a.r.’, Vol 2, Łódź, 1932.

Yet Strzemiński quickly spotted that by Malevich’s logic Suprematism must anticipate the conditions of its own redundancy, its own supercession by a dynamic new norm. Suprematism was in any case a historically transitional form endorsed by the Bolsheviks as a way of defeating classicism and nature-painting. More importantly still, in Suprematism ‘the distance between one form [in the picture] and another is a function of the force of attraction between these forms, and not a valid linear measurement relating to the whole picture’. What then was the ‘additional element’ likely to be capable of supplanting it? Strzemiński, in his ‘Notes on Russian Art’, claimed that the redundancy of Suprematism was more likely to be a subtraction than an addition, namely of anything obstructing or obscuring the operation of laws that were – as he now asserted – peculiar to painting itself.

Fig 1.2 Kasimir Malevich, The Additional, Formative Element in Cubism, c.1924–27, 55.0 × 78.9 cm.

Fig 1.3 Drawing from Kasimir Malevich, Suprematism: 34 Drawings, Vitebsk, 1920.

The opportunity to expand on those ‘laws’ came the following year, 1923, at the Exhibition of New Art in Vilnius, which showed work by Strzemiński together with Henryk Stażewski, Mieczysław Szczuka, Teresa Żarnower and Vytautas Kairiūkštis – all figures of importance for the direction that Strzemiński’s own work would now follow. Strzemiński’s ‘laws’ would be those of flatness (the condition of the stretched canvas); geometry (consonance between interior forms and the shape of the painting); localization of painterly action (absence of reference to events beyond the painting); economy (simultaneity of all visual devices); and a fifth feature that invokes the idea of ‘organicity’ in the painting by means of self-generative multiplication of basic elements to a notionally endless degree, namely, what he called ‘an exponential growth of forms by a juxtaposition of discrepancies’.3 Naturally, they were laws best seen in his own paintings. A work of 1923 named Synthetic Composition 1 shows painted forms within a pictorial ground, as carefully positioned in relation to the painting’s edges as to each other (Plate 1a). Those several forms, delimited with meandering as well as straight borders, all sit within a discernible relation to each other or to the framing edge such as to affirm, through difference and emphasis, that the physical limits of the painting are really there. It is as if Strzemiński wanted his new painting to figure a reconciliation between the forms and the field constituted by the plane of the painting itself. ‘I define art as the creation of the unity of organic form’, he says, ‘through an organicity parallel with that of nature, not identical to it.’ ‘Each entity attains its organicity according to a law proper to itself.’ And then, importantly: the laws of organicity for painting ‘cannot be derived from the structure of any other thing’.4

But what of Productivism, Constructivism’s more practical partner in the early days of Soviet power? This, too, was proving to be a major obstacle in the way of Strzemiński’s ‘organicist’ idea. ‘The baleful influence of Productivism’, he had said in his notes on the Russians, ‘has diverted artists from finding solutions to the problems of organic unity; more especially the reconciliation of pictorial form, not with practical utility, rather with the need for “dynamism” among the painting’s various competing parts.’5 His answer to what he termed the ‘auto-hypnosis’ of Productivism had been forthright and severe. The efficient structures of the OBMOKhU Constructivists (the Stenberg brothers, Rodchenko and Medunetsky) had impressed him as ‘truly new art’, and the work of the young Katarzyna Kobro had been ‘a veritable forward step’ in that context, ‘achieving values that were never attained before’. The OBMOKhU had been exceptional; and their experiments had pre-dated the more recent fetish for ‘production’. Tatlin’s celebrated constructed reliefs, for their part, had done little more than present a machinist image of the modern city ‘such as a rustic from the countryside might have entertained in pre-war days’. In Strzemiński’s view, Tatlin’s favoured materials of iron, glass, concrete, zinc and other metals – the stuff of the American skyscraper, according to Strzemiński – were in reality only decorative, and his Monument to the III International was ‘a formal ruin, a disorganised heap having neither plan nor system, a confused confrontation between a spiral and an oblique’.6

The trouble was that the journal Zwrotnica in which Strzemiński’s writings appeared was itself heavily Productivist, and held out for the closest possible reflection of the new society in the contemporary work of art. The signs were immediately present that Strzemiński would face a theoretical battle over the balance between the social and the organicist functions of art. Zwrotnica was edited by his friend Tadeusz Peiper – someone who had attended Henri Bergson’s lectures in Paris before returning to Poland in 1921, then publishing his own manifesto in the issue of Zwrotnica immediately prior to that in which Strzemiński’s article on the Russians appeared. The position Peiper adopted in his manifesto, entitled ‘Modern City. Mass. Machine’, is itself of some importance. Launched in 1922, it was explicit that in a modern society the working mass was the very condition on which the individual is dependent and through which he or she can lay claim to a public life. ‘The mass as society and the mass as a crowd exerts its ever-stronger influence on the human mind’, said Peiper, ‘and sooner or later will exert its influence on art.’ The history of composition in art had thus far been ‘a kind of tennis-game between rigour and informality’, and Peiper supported organicity as the principle of construction for the work of art only on the condition that ‘the several parts of a work be related to each other by a strict functional dependency, the only possible source of unity in the work … the result of the irrevocable, organic arrangement of its parts’. Mechanist and organicist metaphors had to be closely combined. ‘Society itself is an organism’, Peiper wrote uncompromisingly, ‘productive of the most sophisticated order that can be imagined.’ It is ‘more beautiful than anything that nature has created’ but also ‘as complex and functionally precise as a machine’. Further, mass-society ‘will impose its own construction on art … Society will be a work of art.’7

But it was the overuse of such functionalist imagery that Strzemiński was determined to avoid. And it would not prove easy. He already faced opposition from the artist Teresa Żarnower, a Productivist according to whom the work of art must be strictly utilitarian. ‘Sensations of technology have replaced those of nature’, she said on the occasion of the Vilnius exhibition; ‘it is in machines alone that we can enjoy simplicity and logical construction, qualities that must find their counterpart in the work of art.’8 The challenge was further compounded by the launch in Warsaw of another magazine, Blok, in March 1924, un...