![]()

The Trial: The Defence Cases

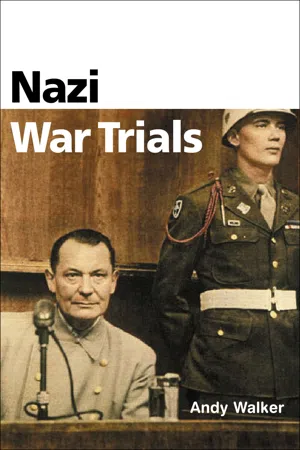

Göring

The news that filtered through to the cells in the Nuremberg prison on 6 March stirred the hopes of the defendants more than anything that had happened since the trial began. The day before Winston Churchill had made a speech, declaring that, ‘From Stettin on the Baltic to Trieste on the Adriatic an iron curtain has descended across the continent. This is certainly not the liberated Europe we fought to build up. Nor is it one which contains the essentials of permanent peace’. Göring in particular was ecstatic over the thought of a growing rift between the Allies: ‘What did I tell you? Last summer I couldn’t even hope to live till autumn. And now, I’ll probably live through winter, summer, and spring and many times over. Mark my word. They’ll be fighting among themselves before sentence can be pronounced on us’.

It was, therefore, with an air of bullish optimism that Göring prepared to be the first defendant to be represented in the case for the defence. The prosecution realised that it was vital to win the case against him. For most of the period of the Third Reich, he was the second most powerful Nazi leader. He had played a key role in establishing the supremacy of the Nazi government in Germany, had been present at all the meetings in which Hitler planned his acts of war, commanded the Luftwaffe, and held overall wartime economic power as Commissioner Plenipotentiary for the Four-Year Plan. If the charges of conspiracy were to stand, a verdict of guilty against Göring would be vital.

The first witness to be called by Göring’s counsel, Dr. Otto Stahmer, was a General in the Luftwaffe, Karl Bodenschatz. He had known Göring from his flying days in the First World War, and had later acted as a liaison officer between Göring and Hitler’s headquarters. Bodenschatz testified that Göring had criticised the attacks on Jewish businesses and property during Kristallnacht, and had opposed war against Britain in 1939 and against the Soviet Union in 1941. The effect of this testimony was undermined by the fact that Bodenschatz had to read from a prepared script. He had been present in the same room as Hitler during the 4 July 1944 assassination attempt, and had still not recovered from the physical and mental scars inflicted by the bomb blast.

It was, therefore, something of a mismatch when Jackson began the witness cross-examination. That Göring had been angered by the destruction during Kristallnacht was not in dispute, but Jackson was able to point out that Göring had ordered the Jewish community to pay for the repairs, and pressured the insurance companies into not paying out on Jewish policies. Bodenschatz began to sweat profusely and became increasingly confused. When challenged about a meeting he had mentioned in his testimony, he confessed that he only knew about it because Dr. Stahmer had told him.This was by no means the toughest opponent Jackson could (or would) face, but the watching defence lawyers marvelled at how destructive the technique of cross-examination, alien to most of them, could be.

Göring’s next witness for the defence was the State Secretary of the Reich Air Ministry, Erhard Milch. He had also been a close colleague of Albert Speer on the Central Planning Board, and was responsible for the allocation of resources and raw materials between the armed services. Milch contested that the Luftwaffe, which Göring had commanded, had been constructed for the purpose of defending Germany, and that any offensive role was secondary. He also repeated the argument that Göring had been opposed to war against the Soviet Union.

Jackson went after Milch with relish. The witness’s position on the Central Planning Board meant that the same material that the prosecution had already presented against Speer and Sauckel could be used to undermine his testimony. When Milch insisted that he thought that all foreign workers in Germany were volunteers, Jackson produced evidence that Milch had been present at a meeting during which Sauckel had stated that only two hundred thousand of the four million foreign workers were there by choice. When Milch denied having a role in any war crimes, Jackson produced a document containing an order from Milch to hang Russian POWs who had attempted to escape. By the time he left the witness stand, Milch had done nothing to help Göring’s cause, and little to help his own.

Field Marshal Albert Kesselring then took the stand, and repeated the claim that Göring’s Luftwaffe was a defensive force. If this were accepted, it would weaken the prosecution’s claim that Göring was guilty of planning to wage aggressive war. Conducting the cross-examination, Jackson asked Kesselring about the ratio of fighters to bombers in the Luftwaffe at the outbreak of war, and drew the admission that there were roughly equal numbers of both aircraft types. Kesselring also had to concede that the Luftwaffe was tasked with supporting the army’s Blitzkrieg style of warfare, so that, while it lacked the long-range bombers present in both the British and American air forces, its purpose could still be explicitly offensive.

The last witness for Göring was a Swedish businessman, Birger Dahlerus. He had been active in the summer of 1939 in a bizarre one-man attempt to broker a deal that would avoid war between Germany and Britain. Dr. Stahmer had called him to testify that Göring had been willing to attend a meeting with Dahlerus and sympathetic British industrialists, and had arranged an audience for Dahlerus with Hitler. Why, Stahmer asked, would a man bent on aggressive war bother to take these steps?

Sir David Maxwell-Fyfe undertook the cross-examination of Dahlerus. He had acquired a copy of the book Dahlerus had written about his exploits, and cordially invited the witness to confirm some of its contents. In the book, Dahlerus had recalled his horrific realisation that, while the Nazis paid lip service to his efforts to negotiate peace, the invasion of Poland was already being planned. In his audience with Hitler, Dahlerus recounted, Göring showed his leader ‘obsequious humility’ while the Fuhrer himself ranted about exterminating the enemy. By the autumn of 1939, Göring was in ‘some crazy state of intoxication’ as he demanded that the Polish government surrender swathes of territory to Nazi rule. It hardly tested the forensic skills of the British barrister to make Dahlerus seem more like a witness for the prosecution than for the defence.

Göring had every reason to be dismayed by the course his defence had taken. The witnesses called on his behalf had done little to help his cause, and had been easily discredited by the prosecution. Despite the political rift that was apparently growing between the Allied powers, it was certain that, if the trial reached its conclusion, Göring would be found guilty. Unlike the other defendants, Göring was now not out to save his own neck, but to speak up for a defeated Germany and to conduct as passionate a defence of the Führer and the Third Reich as he could manage.

Two factors were now in Göring’s favour. The first was the paradoxical advantage his own status within the Nazi regime supplied. While the prosecution was endeavouring to interpret events from outside, Göring had been at the centre of them. In addition, all the evidence was in German, giving Göring an instant understanding of documents, which the prosecution had to handle in translation. The second factor was the effect incarceration had had on him. The prison commandant, Burton Andrus, had arranged for Göring to be weaned off the paracodeine tablets to which he had been addicted. The prison diet and exercise regime had also caused his weight to drop from over eighteen stone to just over thirteen. All this meant that Göring’s mind had sharpened and his mental agility had been restored. Yet, it was still possible for the prosecution to underestimate him. In the robust words of the historian John Tusa, ‘It was still dangerously possible to assume that he was now nothing more than the self-indulgent, pleasure-seeking, drug-impregnated bag of lard with whom Hitler had lost patience and who had sat in Karinhall for two years painting his face and changing his jewellery’.

Göring entered the witness box on Wednesday, 13 March. His shaking hands and constant licking of his lips betrayed his nerves. Stahmer began to ask him a series of short questions and, as he answered, he began to relax. His answers grew longer and more fluent, leaving the court spellbound. Here was the most senior Nazi left alive, recounting graphically and without a hint of remorse, the part he played in the Nazi domination and devastation of Europe. As to the point made by his witnesses that he had opposed the war against the Soviet Union, he was keen to emphasise that his disagreement with Hitler was only on the matter of timing.

After Stahmer had finished his questions, the other defense counsel lined up to gather titbits from Göring, which would help the cause of their clients. Göring seemed happy to help his co-defendants but did little to spare their blushes. Ribbentrop and Rosenberg had no influence with the Führer, he claimed, because they didn’t have his respect. Keitel’s misfortune was that he ‘came between the millstones of stronger personalities’. On the question of conspiracy he was adamant. ‘There was no one who could even approach working as closely with the Führer,’ he claimed, ‘who was as essentially familiar with his thoughts and who had the same influence as I.Therefore at best only the Führer and I could have conspired.There is definitely no question of the others.’

Göring gave a bravura performance for over twelve hours of court time before Robert Jackson rose on 18 March to begin the cross-examination. It has to be borne in mind that, in the insular and feverish atmosphere of the trial, this contest took on a Manichean significance, encapsulating (in the words of the historian David Irving), ‘the conflict between the ordered, civilised milieu of the wing-collared country lawyer, and the swaggering, arrogant, devil-may-care world of the big-time gangster in uniform’.

Jackson began circumspectly, asking open, almost rhetorical questions that sought to establish Göring as an unrivalled expert on Nazi matters. Jackson’s strategy, as he later revealed, was to play on Göring’s vanity, and give him enough rope to hang himself. But it broke the golden rule of cross-examination that you should never ask a question to which you did not already know the answer. Göring was able to respond at leisure and, by picking Jackson up on points of language and interpretation, began to dominate the exchange. Jackson tried to cut Göring’s increasingly expansive answers short, but was reprimanded by Justice Lawrence, who said that the defendant could respond in whatever way he saw fit. Jackson was clearly irritated by the license given to Göring and grew increasingly flustered. By the end of the session, the prosecution had the uneasy feeling that their champion had come off the worse.

The following day Jackson resumed his questions, with an examination of the Nazi plans to wage aggressive war. He focussed in particular on the Rhineland, an area that, under the Treaty of Versailles, had to be kept clear of troops. Göring asserted that plans to re-militarise the Rhineland were not part of some long-term plot, but were cobbled together only a few weeks before the army moved in. Jackson then triumphantly produced a document, which referred to plans for ‘preparation for liberation of the Rhine’ nine months earlier than Göring had claimed. Göring calmly explained that the document had been mistranslated, and merely referred to a procedure for clearing the Rhine of civilian traffic should war occur. Evidently discomfited, Jackson pointed out that the plans were nevertheless kept secret. Göring replied, ‘I do not think I can recall reading beforehand the publication of the mobilisation preparations of the United States’.

This ...