![]()

1

WHAT’S IN A NAME

ON A JUNE EVENING IN 1934, as the day’s lingering heat drifts through a pale-board Baptist church in Lake Arthur, Louisiana, a thundering music resounds off wooden walls and into a microphone; it is sent in lines of cable through the door to a parked Model A Ford with its backseat removed and replaced with five hundred pounds of recording equipment. In the car, powered by two giant Edison batteries, a weighted needle sculpts a groove in a spinning aluminum disc. The machine is recording a song about snap beans.

Engineering the recording is a Texas college student named Alan Lomax who, with his father, John Lomax, is braving the punishing heat of a Southern summer to increase the holdings of the new Archive of Folk Song in the Library of Congress. By this time, the elder Lomax has already made his name as a folklorist: his 1910 book Cowboy Songs and Other Frontier Ballads introduced such standards as “Home on the Range.” In 1932, with support from the Macmillan Company, the Library of Congress, and the American Council of Learned Societies, he set out on a sweeping project of collecting more than ten thousand recordings of folk songs, many performed by Southern blacks. In 1934 alone, John estimated that they traveled thirty-two thousand miles in nine Southern states and recorded about six hundred songs.

Southwest Louisiana has not been an easy stretch, as John Lomax would admit in his annual report. The recording machine is always malfunctioning. Someone steals the tires from their car. Then they overturn their customized Model A and drench their clothes in battery acid. Alan Lomax would later recall that his father decided to stay in their hotel room in Jennings and work on his next book, allowing his son to test his fieldwork skills and college French among the Cajuns and Creoles of Louisiana.

But on this evening in Port Arthur, the church session is on the verge of completely derailing. The aluminum disc spinning, a group of young Creoles form couples and dance around in the church, and a man named Jimmy Peters sings a mournful tune about a woman whose man has not returned home before sundown — an ominous absence, considering the curfew that blacks once had to observe in the area. He wails, “Mon nègre est pas arrivé” — “my man is not home” — accenting the negative pas, heightening the sense of despair. It is a thrilling performance, but after Peters repeats that the soleil après coucher— “the sun is setting” — for the eighth time, the other singers in the church start to get restless and begin talking. One launches into a new song, and others soon join in. A nail is scraped across a rusty slice of metal, and the group launches into a giddy tune about wanting to marry but having no shoes and no money. Peters tries to finish his lament, then he gives up in disgust. Perhaps forgetting that the Library of Congress is recording his words, he starts yelling at his friends. “As it happened,” Alan Lomax would later write in his notes for a reissue of the recordings, “a fight broke out at the peak of the session, and I had to pick up my machine and leave hastily, and thus was unable to find out more about this remarkable music at the time.”

But before Lomax packs up and leaves the church, Peters manages to perform a song in an a cappella style today known as juré (from the French for “testify”) or bazar (probably named for the church social where the music was often made). Against a fantastic background of howling vocals and sharp hand claps, he sings of a man who wanders the land with a ruined hat and a torn suit, too poor to see his woman. His lyrics date back to an old Acadian French folk song, but Peters adds a new phrase that will resonate for generations:

O mam, mais donnez-moi les haricots.

O yé yaie, les haricots sont pas salés.

Oh Mom, give me the snap beans.

O yé yaie, the snap beans are not salty.

Peters doesn’t explain what he means, but the Lomaxes will learn a possible source when they hear the line again in New Iberia, where a worker named Wilfred Charles performs an unusual song about sick Italians, and concludes with:

Pas mis de la viande, pas mis à rien,

Juste des haricots dans la chaudière,

Les haricots sont pas salés.

O! O nègre! Les haricots sont pas salés.

Put no meat, nor nothing else,

Just snap beans in the pot,

The snap beans are not salty.

O! O nègre! The snap beans are not salty!

There is no salt meat to put in the pot with the snap beans. Like early blues musicians throughout the South, the Creoles in Louisiana are singing about poverty.

Many themes in contemporary zydeco lyrics are first heard in the remarkable performances recorded by the Lomaxes. On their journey in Louisiana they meet Paul Junius Malveaux and Ernest Lafitte, who play harmonica and sing “Bye-bye, bonsoir, mes parents” (“Good Night, My Parents”) and imitate a dog in the song “Tous les samedis” (“Every Saturday”); today numerous zydeco songs include choruses of “bye-bye” or dog barks. Also in Jennings, Cleveland Benoit and Darby Hicks sing a haunting blues similar to the song Jimmy Peters couldn’t get through, “Là-bas chez Moreau” (“Over at Moreau’s”). Their voices cresting and falling, Benoit and Hicks trade parts as if completing each other’s thoughts, singing lines about the setting sun and about going to Moreau’s, a wonderful place that holds the promise of sweet candy and brown coffee. Both this song and Joseph Jones’s “Blues de la prison” will be echoed years later in the music of Creole fiddler Canray Fontenot. But it’s the phrase about snap beans — les haricots sont pas salés — that will be carried the furthest.

What’s in a name? Defining “zydeco” is a matter of considerable contention; the remark that someone is or isn’t playing “real zydeco” is today frequently heard at dances. In fact, it is likely that musicians will never agree on the borders of zydeco, because, in true improvisational spirit, they set out to redraw the map in every performance. In 1993 Thomas Fields asked a man in Lafayette named Paul “Papillon” Harris to teach him accordion. “The first lesson this old man taught me,” Fields recalls, “is that you’re not a zydeco player if you can’t make your own music.” Nobody understood this philosophy better than Clifton Chenier.

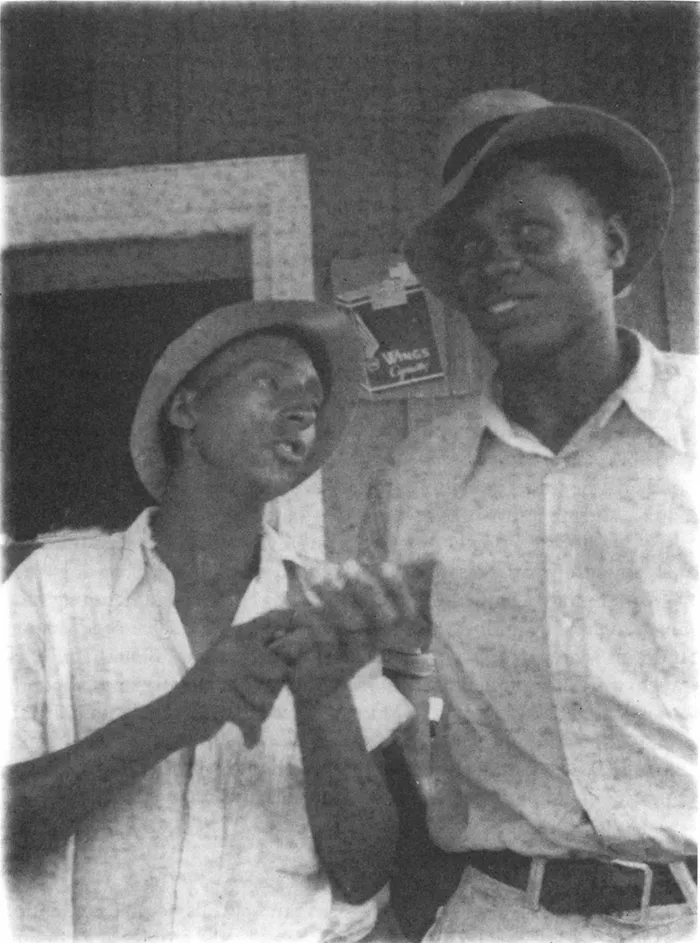

Paul Junius Malveaux and Ernest Lafitte, Jennings, Louisiana, 1936.

It was on May 11, 1965, almost thirty-one years after Jimmy Peters sang about the snap beans, that Clifton and Cleveland Chenier entered the Gold Star studio in Houston. The tape rolling, the brothers shared a few words in Creole French:

CLIFTON: Hé toi. Tout que’que chose est correcte?

CLEVELAND: C’est bon. C’est bon, boy.

CLIFTON: Tout que’que chose est magnifique?

CLEVELAND : O nèg’, quittons amuser avec ça.

CLIFTON: Allons le zydeco!

CLEVELAND: Allons couri’ à lé yé!

(CLIFTON: Hey you. Everything’s all right?

CLEVELAND: It’s good. It’s good, boy.

CLIFTON: Everything’s magnificent?

CLEVELAND: Oh man, let’s go have fun with that.

CLIFTON: Let’s zydeco! CLEVELAND: Let’s go after it!)

Then the pair, backed by drummer Madison Guidry, launched into what would become Chenier’s signature piece, “Zydeco Sont Pas Salé.” On it, Chenier strips down his piano accordion and treats it like an old single-key button model, repeating notes of the same chord. Over this mighty rhythm he sings some lines about two mischievous dogs named Hip and Taïaut that date back to a 1934 Cajun record by Joseph and Cleoma Falcon, “Ils la volet mon trancas” (“They Stole My Sled”); Joe Falcon once explained that he heard the tune from a Creole accordionist named Babineaux. Chenier couples the old song with the lines about the snap beans:

O Mama! Quoi elle va faire avec le nègre?

Zydeco est pas salé, zydeco est pas salé.

T’as volé mon traîneau, t’as volé mon traîneau.

Regarde Hip et Taïaut, regarde Hip et Taïaut.

Oh Mama! What’s she going to do with the man?

The snap beans aren’t salty, the snap beans aren’t salty.

You stole my sled, you stole my sled.

Look at Hip and Taïaut, look at Hip and Taïaut.

In Chenier’s “Zydeco Sont Pas Salé” — today considered the anthem of zydeco — the lines about the snap beans are reunited with the same beat heard on the Lomax recordings. The result still sounds more like a juré performance than anything ever recorded on the accordion, before or since.

What did Chenier have in mind when he made the song? It is highly doubtful that he had heard the Lomax tapes, which were not commercially available at the time. More likely, he had direct experiences with juré when he was growing up in the town of Port Barre, Louisiana. “The beat came from the religion people,” he once told writer Alan Govenar, clapping his hands to demonstrate.

Creole fiddler Canray Fontenot provided more details when he recalled a conversation between the two musicians.

“Clifton was the best on the accordion, and one day, me and Clifton was talking,” Fontenot said. “He said, ‘Say, Canray, a long time ago, they used to have some juré.’ He said, ‘Did you ever go at one of them things?’ I said, ‘No, Clifton, I never did.’ Because they used to have that where they didn’t have no musicians, but I was born where they had some musicians. What it was, them juré, they didn’t have no music, but them old people would sit down, clap their hands, and make up a song. And they would dance on that, them people. Around Basile there, they didn’t fool with nothing like that. I kept saying I wanted to go around Mamou and Ville Platte, where they used to have them juré.

“But Clifton’s daddy was an accordion player, and he said that his daddy played one of them juré songs, and they called that ‘Zydeco est pas salé.’ Which means the snap beans don’t have no salt in them. So Clifton says, ‘That “Zydeco est pas salé” song is good, but the way Daddy played that, that’s the wrong speed.’ He says, ‘I’m going to take that same song, and I’m going to put a different speed on it and them people are going to be able to dance that.’ And he did, too. And when he started, everybody wanted to play the accordion, everybody wanted to play what Clifton played.”

* * *

By the time Chenier recorded the zydeco anthem, the lines about snap beans had been circulating in Houston’s “Frenchtown” neighborhood, where people originally from Louisiana lived and danced. Four years earlier, Albert Chevalier and Sidney “Blind” Babineaux both recorded their own songs with this phrase. “That’s the real zydeco,” Babineaux, then in his eighties, told Arhoolie Records producer Chris Strachwitz. “That’s been here since before I was born, too.”

Yet before anybody made a record about snap beans, zydeco — or les haricots — was a vegetable grown by black Creole farmers.

Snap beans were a spring crop; the harvests started each year around mid-June, and these were often community events. “A lot of times there would be music with the snap bean harvesting,” remembers Wilbert Guillory. “You know, a snap bean is one of the crops that it would take much more labor than any other crop that you put up in the jar, because you would have to break each end, and then you had to pull the little string off. It was very labor-intensive, because your parents wanted them snapped uniformly.

“So a lot of times the neighbors would go around each other’s house and help,” Guillory continues. “They would go to each other with a bucket, and harvest the snap bean, wash it, snap them, and can them. That was more in the later afternoon, mostly when you lay by your other crops. And in that case the music would be done when you were snapping the snap beans. In our community, it was my godfather, Willis Simien, Nolton Simien’s daddy. And while he was playing, we were snapping snap beans and shaking — but not dancing, because you didn’t have much time to dance.”

The story of the snap beans next moves with the black Creoles to the Texas oil towns along the Gulf Coast. In 1901 the modern petroleum age in the United States began in a gusher of oil called Spindletop, near Beaumont, Texas. Starting almost immediately, and peaking through the years of World War II, black Creoles migrated to Texas in search of jobs, bringing along their accordions and French songs. In Houston the old spring crop was nostalgically evoked in music, and two songs recorded in Houston in the postwar era provide the first written documentation of the new sound’s name. One, made sometime between 1947 and 1950, is a tune called “Zolo Go,” recorded by famed blues guitarist Lightnin’ Hopkins at Bill Quinn’s Gold Star studio and released to area jukeboxes. Hopkins was cousin by marriage to Clifton Chenier, and Cleveland Chenier would regularly back him on rubboard; on “Zolo Go” Hopkins mimics Clifton’s accordion with an electric organ, and introduces the song with a short explanation: “I’m going to zolo go a little while for you folks. You know, the young and old likes that.”

The song is clearly a novelty for the guitarist, who never again attempted the style, and it would be quickly eclipsed by a lively R&B/rumba tune by a guitarist from Welsh, Louisiana, named Clarence Garlow. His now classic “Bon Ton Roula” landed in the R&B top-ten chart in February 1950. It recounted the story of “one smart Frenchman” who promises a tour of a “Creole town.” Garlow points out the “church bazaar” and the “French la-la,” then he finishes by making immortal these directions:

You want to have fun, now you got to go

Way out in the country to the zydeco.

Garlow continued to explore these themes in his follow-up songs “New Bon Ton Roulay” and “Hey Mr. Bon Ton,” both recorded in New Orleans in 1953. Also that year, he provided vivid country details in “Jumping at the ...