![]()

1

Relational perception and epistemology

As a matter of philosophical principle, mathematical argument can never tell us, by itself, what the status of nature is. The state of nature can only be discovered from empirical observation.

(Laming, 1997, p. 10)

Introduction

In this chapter on the epistemology of perception and relational psychophysics some basic philosophical questions in the domain of both human and animal perception and cognition are dealt with, namely:

• epistemological implications of perception and cognition

• relational perception and cognitive psychophysics

• the evolutionary perspective on comparative perception.

Modern accounts of the history of psychophysics are provided elsewhere (e.g., Murray, 1993; Murray & Bandomir, 2001; see also Algom, 1992, 2003; Boring, 1942; Link, 2003; Sarris, 2001a, 2004; Sommerfeld, Kompass, & Lachmann, 2001).

Epistemological implications of perception and cognition

The concept of relativity, or relativism, refers to the epistemological principle that all physical and phenomenal events have meaning only with respect to some global or systemic properties that are emergent relative to their components that the latter lack (see Bunge & Ardila, 1987, Figures 5.1, 5.4, 5.5; pp. 90, 101–103). It is important to keep the epistemological, physical and phenomenological “relativity” meanings as fundamentally different from each other.

For example, in his posthumous book The World of Parmenides (1998), the philosopher Karl R. Popper (1902–1994) emphasized the point that already in ancient Greece some of the pre-Socratic thinkers made the fundamental distinction between philosophical and psychological relativism, like Xenophanes of Colophon (about 570–480 bc) in Asia Minor (see also Gold, 2003; Levine, 2003; Nagel, 1995; Norris, 1997; Putnam, 1988). This basic distinction is important in the sense that psychological relativism refers to the organism’s behavioural and mental activity of all kinds, whereas philosophical relativity – doctrine of relativity – denotes a sceptical theory of epistemological inquiry (e.g., knowledge of what things really are is impossible because of the human mind’s basic subjectivity).

Clearly the present monograph deals with psychological and not philosophical relativity and concentrates on a particular type of relativity, namely on perceptual-cognitive relativity.

In the context of social psychophysics it is tempting to assume that ethical relativity in everyday life might be based on perceptual-cognitive relativity. Note, however, that ethical relativity is another world from biophysics or biopsychology. It refers rather to philosophy or metaphysics or religion (Allen Parducci, personal communication, August 2005; see Mussweiler, 2003; Parducci, 1995; see also Rorty, 1991). Interesting as this speculative conjecture is, not only for psychology, it is beyond the scope of this book.

Phenomenology as a guide to behavioural and brain research

Phenomenology is a term related to the scientific study of immediate experience (“appearance”) as the basis of perceptual psychology. Its focus here is on subjective events as one experiences them. However, there is no attempt made to disregard or deny the physical and chemical reality of objective events, but the basic issue for a phenomenological approach is to avoid the exclusive focus upon the objective, i.e., non-subjective reality (see the illustrations provided by Figures 1.1 and 1.2).

The importance of phenomenology for perceptual research, emphasized by gestalt psychology, has hardly seen more creative proponents than Max Wertheimer (1880–1943) and Gaetano Kanizsa (1913–1993). Through careful observation and artful variation of visual phenomena, Wertheimer and Kanizsa – together with their colleagues and students – revealed the puzzling and intriguing richness of perceptual appearance. Indeed, phenomena are immediate (direct) and undeniable facts of experience and hence a prime source of scientific investigation. Their systematic observations and descriptions are fundamental in the light of the respective state of knowledge about sensory and brain functions as well as of the physical properties of the stimulus relationships (e.g., Ehrenstein, Spillmann, & Sarris, 2003).

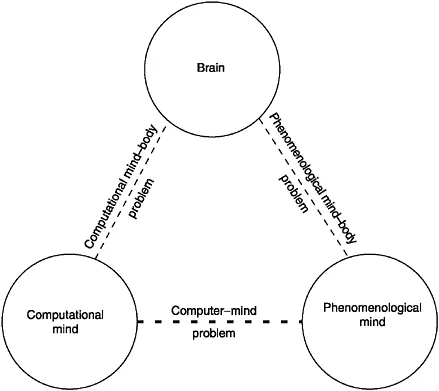

Phenomenal description, however, is just the starting point of modern perceptual research and far from being self-sufficient (Figure 1.1). Besides the “phenomenological mind” there are nowadays also the neurobiological and computational approaches (Kubovy, 2003; see also Cruz, 2003; Spillmann & Ehrenstein, 2004). Closely related to this fundamental issue is the concept of “gestalt” as an emergent property (e.g., Bunge & Ardila, 1987; Kubovy &

Gepshtein, 2003). In comparing human and animal perception with each other, one has to rely on the systematic study of behavioural observations. Such research, which must be guided by sound phenomenology, illustrates one of the explanatory gaps (Figure 1.1; see also Nagel, 1974, 1995, 1997). Combining phenomenal approaches with neurophysiology must not be confused with neurophysiological reductionism.

After all, phenomena in their quality are independent of the knowledge of the brain processes underlying them (admittedly, the broken lines in Figure 1.1 illustrate the fundamental explanatory gaps). In other words, percepts do not become deprived of anything if they are “consulted” by neurobiological experts in order to understand the functional processes that subserve them. Epistemologically, phenomena per se can rather serve to broaden and deepen the understanding of brain functions since they may give us the primary clues of why things “look” as they do (e.g., Mausfeld, 2002; see also Koch, 2004; Kubovy & Gepshtein, 2003).

The argument here is in favour of a wider scope of phenomenology, traditionally resident in philosophy and psychology, to enrich the perspectives of a modern gestalt psychophysics as tightly linked to behavioural and brain research. In fact, there is nowadays an increasing dialogue between the neurophysiological and psychophysical approaches so that with David Hubel, the renowned neurobiologist, one may hold that “gradually we are coming to understand each other’s language and are mastering each other’s techniques. The field has become immeasurably richer” (Hubel, 1995; quoted after Ehrenstein et al., 2003, p. 452).

Relational perception and cognitive psychophysics

As implied by the introducto...