eBook - ePub

Doctor Zhivago

Ian Christie

This is a test

- 100 páginas

- English

- ePUB (apto para móviles)

- Disponible en iOS y Android

eBook - ePub

Doctor Zhivago

Ian Christie

Detalles del libro

Vista previa del libro

Índice

Citas

Información del libro

The multiple award-winning Doctor Zhivago (1965) is one of America's finest films of all time. Ian Christie contextualizes the film as an epic Russian love story and a Cold War classic, charts its production and reception, including the contribution of designer John Box, and discusses the unique history of the Bruce Pasternak novel it is based on.

Preguntas frecuentes

¿Cómo cancelo mi suscripción?

¿Cómo descargo los libros?

Por el momento, todos nuestros libros ePub adaptables a dispositivos móviles se pueden descargar a través de la aplicación. La mayor parte de nuestros PDF también se puede descargar y ya estamos trabajando para que el resto también sea descargable. Obtén más información aquí.

¿En qué se diferencian los planes de precios?

Ambos planes te permiten acceder por completo a la biblioteca y a todas las funciones de Perlego. Las únicas diferencias son el precio y el período de suscripción: con el plan anual ahorrarás en torno a un 30 % en comparación con 12 meses de un plan mensual.

¿Qué es Perlego?

Somos un servicio de suscripción de libros de texto en línea que te permite acceder a toda una biblioteca en línea por menos de lo que cuesta un libro al mes. Con más de un millón de libros sobre más de 1000 categorías, ¡tenemos todo lo que necesitas! Obtén más información aquí.

¿Perlego ofrece la función de texto a voz?

Busca el símbolo de lectura en voz alta en tu próximo libro para ver si puedes escucharlo. La herramienta de lectura en voz alta lee el texto en voz alta por ti, resaltando el texto a medida que se lee. Puedes pausarla, acelerarla y ralentizarla. Obtén más información aquí.

¿Es Doctor Zhivago un PDF/ePUB en línea?

Sí, puedes acceder a Doctor Zhivago de Ian Christie en formato PDF o ePUB, así como a otros libros populares de Medios de comunicación y artes escénicas y Películas y vídeos. Tenemos más de un millón de libros disponibles en nuestro catálogo para que explores.

Información

1 How Zhivago Happened

Several years ago, I was at a small garden party in North London, and gradually realised that I was sitting close to Julie Christie. What should I do? Pretend not to be aware of who she was, or launch into some appropriate conversation? Not wanting to embarrass the actress, I eventually said something about being fascinated by the colour design of Doctor Zhivago, after recently writing a book about its designer, John Box. Especially the blaze of yellow that lights up the library where Christie’s character, Lara, is working when Zhivago rediscovers her after they have been separated by the Revolution. Immediately, Christie’s face lit up at what seemed to be still a vivid memory, and I felt I had touched a chord that meant something to both of us, far beyond talk about the making of the film or its more obvious reputation. And indeed, that moment was a key image for the film’s writer, Robert Bolt – who imagined ‘an ocean of daffodils’ for the scene that leads up to this fateful meeting – soon after he first agreed to write the script.1

I had come back to the film because of my association with the production designer John Box. Having committed to writing a book about his vision of the designer’s role, I had to take on board the full range of films he had worked on, of which Zhivago was probably the best known, after Lawrence of Arabia (1962). And as with Lawrence, I was conscious of having to overcome the prejudices of youth. During the 1960s and 70s, when ‘film studies’ was still taking shape as a field of study, polemic played a vital role in defining the new subject. It was as important to declare what you were against in cinema as what you were championing. And David Lean’s ‘epics’ Lawrence and Zhivago came high among the targets of cinephile contempt. During the years I spent arguing for Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger’s then little-known work, Lean also stood as a baleful comparison, with his seemingly overblown triumph, at a time when neither of his former mentors could get their own projects off the ground.

By the time I came to know John Box, I had developed a high regard for Lean’s films of the 1940s and 50s, especially his skilfully modernised, and very English, family melodramas, from This Happy Breed (1944) to The Passionate Friends (1949). This was probably helped by film studies, now firmly established, having enthusiastically embraced melodrama, encouraged by its alliance with feminism during the 1970s, and arguing for films such as those of Douglas Sirk that had long been scorned as ‘women’s fiction’. Getting to know John Box led me to view and re-view not only the films he had designed for Lean, but also those that had influenced him, such as Lean’s two Dickens adaptations, Great Expectations (1946) and Oliver Twist (1948), brilliantly conceived by one of his mentors, John Bryan. Coming back to Zhivago, I was seeing it through very different eyes.

Doctor Zhivago is of course many things. Despite an initial, and somewhat exaggerated, critics’ drubbing, it became, as the late Omar Sharif says in his DVD introduction, ‘an instant hit with romantics worldwide’. And for a vast audience, it still represents the epitome of modern romantic fiction, with the poet Zhivago and his beloved Lara ensconced in an ice-bound dacha, temporarily safe from the tides of revolution breaking around them. For others, it is a chronicle of disillusion with the Russian Revolution by the poet Pasternak, possibly overreaching himself in attempting the epic scale of Tolstoy’s War and Peace. And for many, it stands as a monument, heroic or outdated depending on taste, to the heyday of the movie blockbuster, epitomised by the original MGM poster of its stars dwarfing the historical events that surround them. But it is unquestionably two material, historic things: a novel that became a worldwide best-seller and a political cause célèbre like no other in the mid-twentieth century; and a hugely popular film starring Julie Christie and Omar Sharif that won five Academy Awards in 1966, with theme music by Maurice Jarre that became inescapable for decades.

If the relationship between these has hardly been a subject of much critical attention, this is probably due to the assumption that a serious novel could not become a popular film without gross simplification or distortion. So is it worth trying to keep Pasternak’s novel in view as we consider Lean’s film? Up to a point I believe it is, although the novel should not be invoked to belittle the film, as we look back at two works that are now half a century old, both belonging to an era we struggle to recall, when books and films could shake the foundations of the cultural and political world.2

Boris Pasternak and the Zhivago storm

Perhaps the most famous anecdote about Boris Pasternak, the highly regarded poet who turned to prose for this solitary novel, concerns his only direct contact with Josef Stalin. In 1934, with Stalin’s drive for conformity among artists in all media gaining momentum, the dictator telephoned the poet. Shortly before, a fellow Russian poet, Osip Mandelstam, had been arrested by the People’s Commissariat for Internal Affairs (NKVD), and Pasternak tried to use his influence to get Mandelstam released. As a result, the phone rang in his apartment and ‘Comrade Stalin’ was announced. According to some accounts of what followed, Stalin asked, ‘What are they saying in your circles about the arrest of Mandelstam?’ Most, however, agree that Stalin assured Pasternak the poet’s case had been reviewed and he would be safe, before the bizarre reproach: why hadn’t Pasternak done anything to help Mandelstam? ‘If I were a poet, and a poet friend was in trouble, I’d do anything to help him.’ Pasternak would be haunted for the rest of his life by what happened next. His rambling answer apparently involved denying that there was any discussion of the case and explaining that ‘friend’ wasn’t the right way to describe their relationship. According to some versions, Stalin insisted, ‘But he’s a genius’, to which Pasternak replied that this wasn’t the point; and in another account, Stalin accused Pasternak of ‘not being able to stand up for a comrade’.3

Whatever the details, Pasternak was thunderstruck by this surreal conversation with a figure who fascinated him – and whose responsibility for Mandelstam’s plight, among so many other arrests, was ignored. He told the story of the phone call endlessly, blaming himself in the terms that Stalin had blamed him, and so helping spread the rumour of Stalin’s personal ‘intervention’ on behalf of Mandelstam. In fact, Mandelstam was rearrested in 1938 and died soon after in a prison camp during the Great Purge. Pasternak, however, was never arrested, and his survival has been credited to Stalin’s respect for his genius, and the note written against his name on an execution list, ‘Do not touch this cloud-dweller.’

Immediately before and during the Second World War, Pasternak showed considerable courage, first refusing to sign a condemnation of senior officers during the Purge, despite strong pressure to do so; then making visits to troops to give poetry readings and boost morale. After the Allied victory, Stalin’s paranoia led to wholesale imprisonment of returning veterans and renewed persecution of intellectuals. But Pasternak’s own life took a new turn when the married writer met Olga Ivinskaya, a writer and young single mother, in October 1946 and fell in love with her. He had hoped to write a long novel for many years, probably since 1932 or even earlier; but inspired by his new love, he returned to what would become Doctor Zhivago and completed the manuscript in 1954. During this time, Ivinskaya paid a terrible price for her relationship with Pasternak, being arrested and imprisoned in 1949, and miscarrying their child in the process.

The novel now reflected their own story and aspirations, with Yuri Zhivago a married poet who falls in love with a nurse, Larissa (Lara), and, amid the chaos of the civil war, spends an idyllic few months at a remote dacha, before they finally separate and he returns to Moscow. The novel ends with a collection of poems attributed to Zhivago, which include many dedicated by Pasternak to Olga. But any hopes that it could be published in the Soviet Union, even during what became known as ‘the Thaw’ under Khrushchev’s leadership, were soon dashed when the editors of the journal that Pasternak submitted it to denounced the novel as ‘anti-Soviet’ and accused its author of being ‘alienated’ from his own society. Frustrated and disillusioned, Pasternak began to act recklessly, giving typescripts to different messengers to take abroad. One of these reached the Italian Communist publisher, Giangiacomo Feltrinelli, and the furious negotiation, not to mention anguish, that this created has only recently been revealed in Paolo Mancosu’s aptly titled book Inside the Zhivago Storm.4 But Feltrinelli was not the only interested party abroad. The CIA had also decided that the novel could be a major weapon in their propaganda war, and were actively trying to have it published in Russian and smuggled into the USSR.

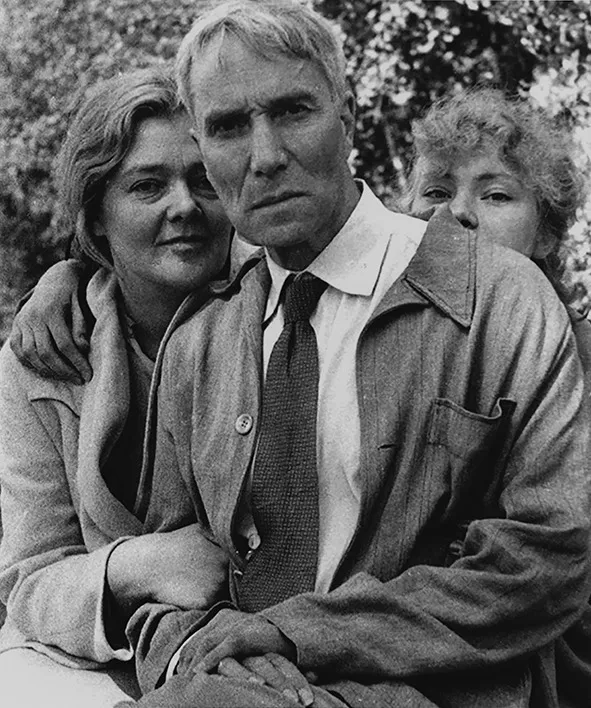

Boris Pasternak c. 1959, with Olga Ivinskaya and her daughter Irina: the relationship that inspired Doctor Zhivago and its story of a romantic passion that transcended the lives of those involved (courtesy of Andreï Kozovoï)

Another recent book by Peter Finn and Petra Couvée has anatomised The Zhivago Affair, with its many players and spy-story twists (including smuggled rolls of microfilm involving Britain’s MI6), which led to a special Russian-language edition being distributed at the Brussels International Exposition through the Vatican pavilion!5Meanwhile, Feltrinelli’s Italian edition of 1957 had been rapidly followed by translations into most main languages, and Zhivago becoming an international phenomenon. Despite some negative views, notably from the émigré Russian author Vladimir Nabokov, then enjoying English-language success with his novel Lolita, both critics and public seemed convinced that this marked ‘one of the great events in man’s literary and moral history’, as the American critic Edmund Wilson hailed it.6

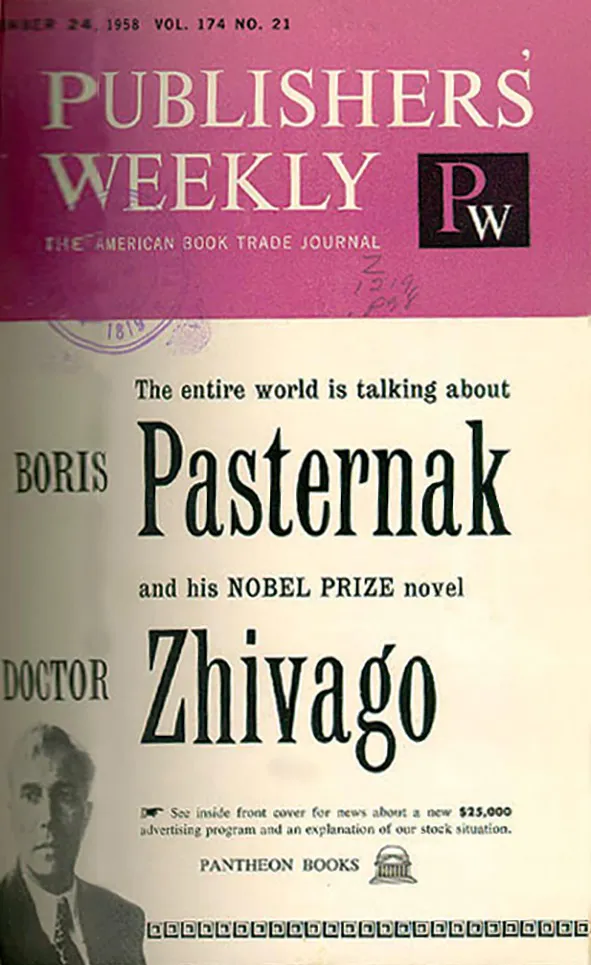

To cap it all, 1958 ended with the award of the Nobel Prize for Literature to Pasternak, linking Zhivago with the body of his earlier poetry and prose that had made him a contender for many years. The political storm in the Soviet Union was now intense. With the Cold War at its height, Pasternak was attacked from all sides, on Khrushchev’s orders. Told that if he travelled to Stockholm he would be refused re-entry to Russia, Pasternak wrote to explain that he could not accept the award, creating even more anti-Soviet publicity in the process, and further increasing interest in Zhivago. Pasternak died two years later, his life probably shortened by the strain of surviving the Nobel Prize affair and the continued Soviet attacks on his integrity. Olga Ivinskaya was again arrested, on a trumped-up charge of currency speculation, although neither she nor Pasternak’s wife ever benefited from the book’s vast sales abroad. And although a later Soviet dissident, Alexander Solzhenitsyn, would criticise Pasternak for refusing the Nobel Prize, his very survival to continue writing and die a natural death set a historic example. Whether or not Zhivago ultimately measures up to either Tolstoy or Solzhenitsyn, it remains a literary landmark and the first modern Russian novel to enjoy an international impact.7

Pasternak’s Nobel citation was for his poetry and achievement ‘in the field of the great Russian epic tradition’

Starting the journey to the screen

The worldwide success of the novel virtually guaranteed that there would be strong interest in a film version. And because it effectively belonged to its Italia...