![]()

1

TO THE UNDERWORLD WITH ONONTI THE SHAMANESS

Rajingtal, 1975–76

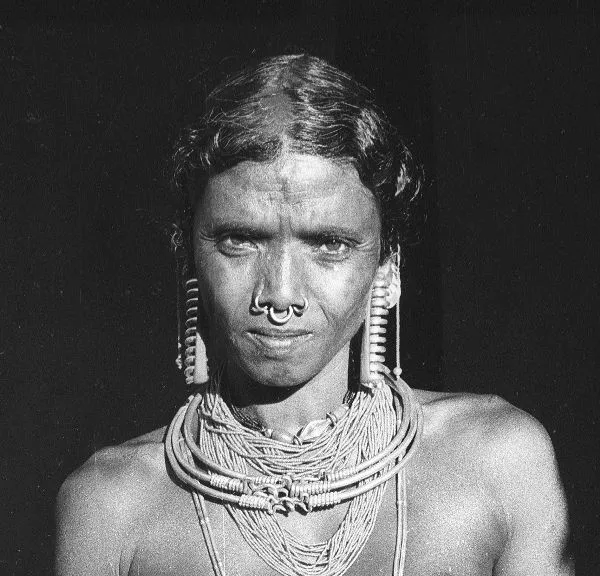

Ononti—my first shaman, small and shrewd, secretive but humorous. So archaic that she could not recognize a human face in a photograph. A woman who could not sustain her marriage with a living husband, but who found fulfillment in dreams and trances by marrying a being in the Underworld.

I can still visualize Ononti as I first saw her in 1975, performing a funeral to transform a dead man from a ghost (kulman) into a proper spirit, a sonum, by going into trance and bringing him back to talk through her mouth with his living mourners. This Ononti is still quite young, yet she already has the lean face and forward-thrusting jaw of many older Sora women whose soft rounded features of their youth have been sharpened by toil and undernourishment.

In contrast to the dark-skinned and heavily dressed Hindu castes of the plains, the Tribal Sora have slightly upturned eyes and reddish-brown skin that glows against the cream homespun cotton of the women’s knee-length skirts and the loincloths of the small, wiry men. Both women and men wear nothing above the waist except necklaces, nose-rings and earrings, and for women, huge circular wooden earplugs. The silver and gold come from bazaars in the plains that pulsate with bright colors in cotton, nylon, and plastic, but here in the Tribal hills most artifacts are homemade and share the color of the wood, leaves, and mud from which they are crafted; even the tiger stripes and moon discs on Ononti’s face are tattooed with a thorn and dyed with the indigo-blue juice of a jungle berry.

Ononti, the great funeral shaman of Rajingtal village, purses her lips outward as she gives commands: lay out the mat like this, bring the pot of palm-wine over here, put the leaf-cups of rice offerings over there. Her long black hair is swept back into a bun and held in place with large silver hairgrips. The midday sun sprinkles her brow with sweat, which trickles over the pile of beads in her necklaces and down her bare chest. How often have I seen her sit on the ground like this and stretch her spindly shins and rock-toughened feet straight out in front ready for trance, while the audience—mostly other women—squat on their haunches around her in a huddle waiting for their dead relatives to appear?

Closing her eyes and turning a knifepoint on the ground in time to her chant, Ononti starts to sing in parallel couplets, repeating each line but changing one word at a time to enrich the meaning. I cannot yet follow any of this, but am told that she is calling on the female shamans who have lived before her for help as her soul starts to clamber “like a monkey” down the precipices that lead to the Underworld.

| | |

| | |

| | |

| | |

| | |

| | |

clasping hands, grandmothers, | along the one-hand narrow path |

clasping feet, grandmothers, | along the two-cupped-hands narrow path |

| | |

| | along the impossible-balancing path |

your monkey four-footed gait, | |

your simian four-footed gait, | |

Her husky voice is momentarily overwhelmed by dancers as they surge past, raising a brief cloud of grit and shortening the life of yet another cheap cassette recorder on which I am filling tape after tape with words I cannot understand. The dancers loom over us, drums pounding, oboes blasting, women flexing alternate knees while hardly lifting their feet off the ground, men hopping from foot to foot. Some adults and older children have a sleeping infant on their hip jigging up and down in a sling, its ringed, snotty nose pressed against their body. Little girls bounce up and down in twos and threes with arms linked behind their backs, homemade cigars tucked behind their ears and tassels of long hair flying from the crown of their shaved heads. The dancers twirl on one foot as they brandish battleaxes, or black umbrellas as a substitute. There is an occasional outburst of whistling, war cries, and the bray of a brass horn from B up to F-sharp and back again. A sudden change of direction makes the densely packed body of dancers seem like one creature as they spill over a dike, fanning out, stomping, and spinning into a dry out-of-season paddy field.

The drums never stop, but now they are drifting far away. Nearby, with soft thumps, a dozen buffalo are being bashed on the skull to send their souls down to the dead man in the Underworld. After a long invocation, Ononti’s voice peters out, and her head flops down onto her breast. Her soul too has reached there, leaving her body available to convey the voices of the dead as they come up one by one. In this deep trance her limbs have gone rigid, and bystanders rush forward to unclench them. It takes several people to flex her knees with a jolt and lay her legs straight again along the ground, and to unclench her fingers and bend her elbows before returning her hands to rest, limp, along her outstretched thighs.

Ononti sits motionless, then with a sharp intake of breath her body twitches, and the first in a long line of sonums announces its name. The first is a special helper (ılda), her sonum husband from the Underworld; others are her shaman predecessors and teachers (rauda), but most are the dead relatives of the man for whom they are planting a stone today, adding to the patrilineage’s cluster (ganuar) of memorial standing stones. Some ancestors (idai) just stay for a brief chat and a drink of wine (palm toddy, alin) and a puff on a cigar, which Ononti imbibes on their behalf. But the dead man himself spends twenty minutes talking to his relatives. Sometimes the women weep; sometimes they engage him in heated arguments that draw in men too; occasionally there is a whoop of laughter.

What kind of miracle-worker is this tiny woman with limpid brown eyes who orchestrates the feelings of a community by incarnating those who have been close to them and bringing them to engage in dialogue? What are the living and the dead saying to each other—about his last illness, about his inheritance, about love, grudges, domestic trivia, sex? What kind of theater is she staging for her clients as they embrace her body in their longing for a dead man who no longer has flesh of his own? What is she herself feeling as she “becomes” him? And what can it mean for everyone to believe in all this?

For my first few months in Soraland I crouched beside Ononti, helping to loosen her limbs and hanging on to any word I could grasp. I did not know enough about my hosts’ family dynamics, or even about their language. I was sure that these conversations were vital for understanding everything, but I did not yet know how much of my life I would devote to decoding them. Later there would be many more shamans, both women and men, in different villages and with different quirks of secrecy and openness. However, Ononti would remain the most enigmatic of all, from our first meeting in 1975 right up to her death thirty years later, and the occasion six months after that when her pupil Lokami went into trance and brought Ononti back to speak with me once again. Now that most young Sora have joined evangelical Christian or fundamentalist Hindu movements, those crackly, distorted cassette tapes bring back a world that is lost forever.

....

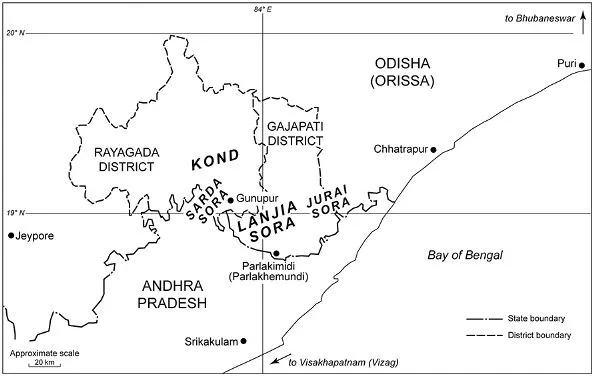

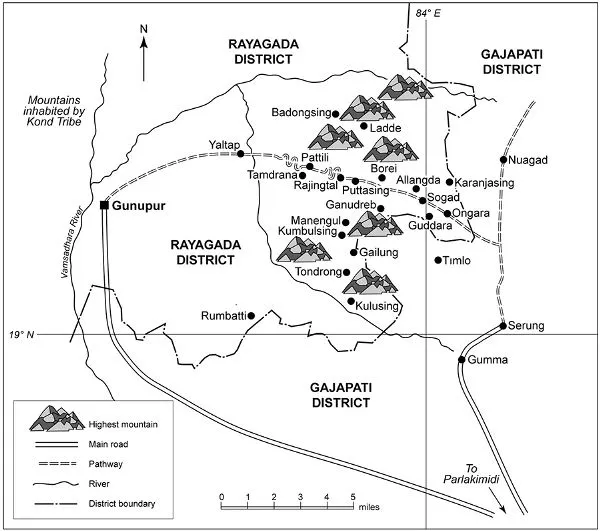

The Sora are one of many peoples in central India who are called “Tribal” (adivasi: in India the English word “Tribal,” whether as adjective or noun, amounts almost to an ethnic label, and so I have spelled it with a capital T). India contains several hundred “Scheduled” tribes, totaling over 100 million people, around 8 percent of the country’s population (see the online bibliographic essay). Among these tribes, the Sora seem to have been the early inhabitants of a large area of eastern and central India, probably predating the much more numerous speakers of Indo-European and Dravidian languages who now live around them to the north and south, respectively. The Sora language belongs to the South Munda branch of the Austroasiatic family, a family that includes Cambodian and the languages of jungle peoples in Malaysia and Vietnam. The Roman historian Pliny located the “Suari” (i.e., Sora) along the eastern coast of India, and I have traced Sora village names far outside their present reduced range in the marginal region between the states of Odisha (until 2011 spelled Orissa) and Andhra Pradesh (with additional migrant communities in Assam). Today they number several hundred thousand, encompassing several subtribes and dialects, such as Sarda Sora and Jurai Sora. I have lived with the Lanjia Sora, the most remote and “Tribal” group, who are not enumerated separately but number perhaps 100,000 or more, in the most mountainous Sora heartland. This area is generally inaccessible to outsiders, and my periods of residence there over forty years, speaking Sora and living in Sora houses as a researcher in the 1970s and subsequently revisiting old friends, have been unique.

A people of the jungle with an ancient reputation for wildness, the Sora have lived for millennia in an ambiguous relationship with the Hindu world of rajas and temples. Both scholars and politicians argue about whether and how far the Sora and similar tribes are “really” Hindu. The Brahmin priests in the huge temple at Puri even claim that they stole their great Hindu god Jagannath (Juggernaut), now seen as an avatar (incarnation) of Vishnu, from a primitive Sora cult in the jungle. I shall call the indigenous Tribal religion “animist,” partly to distinguish it from other more classically Hindu movements in chapter 11 but also because this seems the best description of their understanding of the world. I use “animism” not as a primitivist category or as something residual when “world religions” are subtracted, but as a serious descriptive term for a cosmology in which features of the environment such as rocks and trees are considered to have a consciousness similar to that of humans. I shall later argue, however, that Sora are animists of a particularly humanistic kind. A discussion of these terms, along with references, will be found in the online bibliographic essay at press.uchicago.edu/sites/Vitebsky.

I was alerted to the Sora by a fascinating book by Elwin (1955), and in October 1974 I registered for a PhD in social anthropology at the School of Oriental and African Studies in London. In January 1975 I set out on a month’s overland trek to Bhubaneswar, the state capital of Orissa, for a preliminary reconnaissance. I was hospitably received at the local university, but was told that the Sora were almost impossible to reach. An irresistible challenge! I bought a bicycle and pedaled for three days to Parlakimidi (now Parlakhemundi), a small town at the foot of the Sora hills that turned out to have bus connections after all, and then cycled a further twenty miles uphill to a Canadian Baptist mission hospital in a village called Serango (in Sora, Serung).

It was here, at “Bethany Bungalow,” that I first learned to say lemtam, sukka po, wan yirte? (Hello, are you well, where are you going?). The missionary, Melville J. Otis, was a white man like myself, but bearded and with the glinting blue eyes of a religious ascetic. The New Testament had been translated into Sora by previous missionaries, and Mel was working on the book of Genesis at the start of the Old Testament. Non-Christian Sora had no writing, but the early missionaries had worked with a local Hindu scholar called Ramamurti to devise a script based on the Roman (Latin) alphabet with additional elements from the International Phonetic Alphabet. Mel’s small team of Sora assistants included Monosi, who looked severe behind heavy black-rimmed glasses but would later become my closest friend and collaborator; and Monosi’s mentor Damano, an elderly Baptist pastor who had lost an eye to a bear. Mel generously took me to services and weddings in surrounding villages, which all seemed to be Baptist. Relations between anthropologists and missionaries are traditionally prickly: we come to study a culture, they come to change it. I am not a Christian anyway, so I am surprised now to read in my notes: “God is in his mind every moment of the day and in everything he says and does, and it’s a strengthening and joygiving state.”

I was grateful for Mel’s hospitality, but wary of the bungalow’s seductive comforts, and keen to move on.

“Which area has the biggest shamans?” I asked him.

“I’m an ambassador of the King of Kings!” he parried. “Such things are not my business!”

I became more cunning, and waited. Turning the question around, I asked, “Where are you having the least success at converting?” He fell into the trap and named the area around Rajingtal and Sogad, where I have since spent much of my life.

I was told (correctly) that Sora would not work for money, so I hired a guide from the Pano, a Christianized “untouchable” caste who speak Oriya (or Odiya, the main language of Odisha) but a...