eBook - ePub

These 6 Things

How to Focus Your Teaching on What Matters Most

Dave Stuart

This is a test

Compartir libro

- 272 páginas

- English

- ePUB (apto para móviles)

- Disponible en iOS y Android

eBook - ePub

These 6 Things

How to Focus Your Teaching on What Matters Most

Dave Stuart

Detalles del libro

Vista previa del libro

Índice

Citas

Información del libro

Dave Stuart Jr.’s work is centered on a simple belief: all students and teachers can flourish. These 6 Things is all about streamlining your practice so that you’re teaching smarter, not harder, and kids are learning, doing, and flourishing in ELA and content-area classrooms. In this essential resource, teachers will receive:

- Proven, classroom-tested advice delivered in an approachable, teacher-to-teacher style that builds confidence

- Practical strategies for streamlining instruction in order to focus on key beliefs and literacy-building activities

- Solutions and suggestions for the most common teacher and student “hang-ups”

- Numerous recommendations for deeper reading on key topics

Preguntas frecuentes

¿Cómo cancelo mi suscripción?

¿Cómo descargo los libros?

Por el momento, todos nuestros libros ePub adaptables a dispositivos móviles se pueden descargar a través de la aplicación. La mayor parte de nuestros PDF también se puede descargar y ya estamos trabajando para que el resto también sea descargable. Obtén más información aquí.

¿En qué se diferencian los planes de precios?

Ambos planes te permiten acceder por completo a la biblioteca y a todas las funciones de Perlego. Las únicas diferencias son el precio y el período de suscripción: con el plan anual ahorrarás en torno a un 30 % en comparación con 12 meses de un plan mensual.

¿Qué es Perlego?

Somos un servicio de suscripción de libros de texto en línea que te permite acceder a toda una biblioteca en línea por menos de lo que cuesta un libro al mes. Con más de un millón de libros sobre más de 1000 categorías, ¡tenemos todo lo que necesitas! Obtén más información aquí.

¿Perlego ofrece la función de texto a voz?

Busca el símbolo de lectura en voz alta en tu próximo libro para ver si puedes escucharlo. La herramienta de lectura en voz alta lee el texto en voz alta por ti, resaltando el texto a medida que se lee. Puedes pausarla, acelerarla y ralentizarla. Obtén más información aquí.

¿Es These 6 Things un PDF/ePUB en línea?

Sí, puedes acceder a These 6 Things de Dave Stuart en formato PDF o ePUB, así como a otros libros populares de Education y Teaching Languages. Tenemos más de un millón de libros disponibles en nuestro catálogo para que explores.

Información

Chapter One Teaching Toward Everest

Photo by Alyssa Roelofs.

Clarity of purpose . . . consistently predicts how people do their jobs . . . . The fact is, motivation and cooperation deteriorate when there is a lack of purpose. If a team does not have clarity . . . problems will fester and multiply. When there is a lack of clarity, people waste time and energy on the trivial many.—Greg McKeown (2014, p. 121)

Greatness and nearsightedness are incompatible. Meaningful achievement depends on lifting one’s sights and pushing toward the horizon.—Daniel Pink (2009, p. 58)

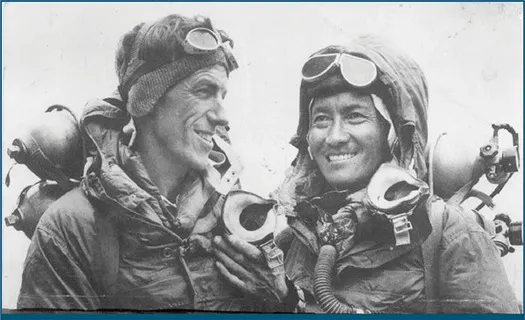

In May 1953, Edmund Hillary and Tenzing Norgay, pictured in Figure 1.1 on the next page, faced a daunting task that no one had yet accomplished: ascending Mount Everest and living to tell the tale. Unlike climbers of Everest today, Hillary and Norgay did not have the benefit of charted territory. They faced the death zone, a place where the body is actively dying. They were climbing at an altitude nearly as high as the airplanes of their day flew. The risks were many, and the reward was glory.

For two important reasons, the work that you and I try to do each year is far more challenging than what those two men faced in 1953. Sure, there’s little chance that a day in the classroom will end with frostbite on our noses or our frozen corpses buried by avalanche, but our job is still tougher.

First of all, Norgay and Hillary’s task was fairly simple to articulate, and ours isn’t. If you were to ask one hundred random people who knew of Norgay and Hillary back in early 1953, “Hey, what are these gentlemen trying to accomplish this year?” most answers would be identical:

“They’re trying to climb Mount Everest. Duh.”

Figure 1.1 • Sir Edmund Hillary and Tenzing Norgay, on May 29, 1953, after completing the first successful ascent of Mount Everest.

Source: commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Edmund_Hillary_and_Tenzing_Norgay.webp, printed under CCBY-SA 3.0.

But if I were to poll one hundred people in your life this year, asking them, “Hey, what is this teacher supposed to accomplish in her job this year?” I’d be shocked if there were even two identical answers, and I wouldn’t be surprised if there were some answers that seemed to describe an entirely different profession in a wholly different galaxy. Depending on whether the respondent was your administrator or one of your students or a community member or your state’s governor or your school of education professor, I’d be in for a whirlwind of ideas and expectations, wouldn’t I? There would be multiple full-time jobs represented in those responses.

This incoherence of purpose and its attendant avalanche of expectations is a more insurmountable obstacle than a thousand Everests on top of one another. If this book—or any book—is going to help our teaching practice, then this mountain must be demolished. We can’t ignore it. So, let’s do something crazy, shall we? Let’s place the power of purpose setting in the hands of some people who might know a thing or two: you and me, the people on the ground doing the work alongside our students. Right now, before you do anything else, I’d like you to take half a minute and, without mental editing or revision, answer something in writing:

What, in a single sentence, is your Everest this school year? What do you hope that your work will amount to?

Be as specific as you can be. Ideally, you’d like to know during a given lesson whether or not you have made progress toward your Everest.

My Everest:

__________________________________

__________________________________

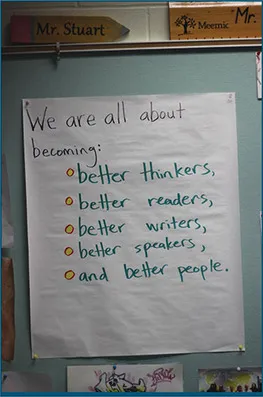

If you visit my room and sit with my students during a lesson, you’ll see, just left of the whiteboard, a simple poster that reads “We are all about becoming better thinkers, readers, writers, speakers, and people” (see Figure 1.2), And on any given day, whether you walk into a world history class or an English class, my students and I know that we had better be working toward one or more of the things on that poster or else we’ve lost our way. This sentence—more than an impossibly long list of standards, more than the latest list of 28 “priorities” from on high—is what informs my daily, on-the-ground work. There is no sentence that more shapes my classroom, its work, and its culture than this yellowing old anchor chart. Clarity of purpose is necessary for teachers and students alike.

Figure 1.2 • “We are all about becoming . . .” Poster in My Classroom

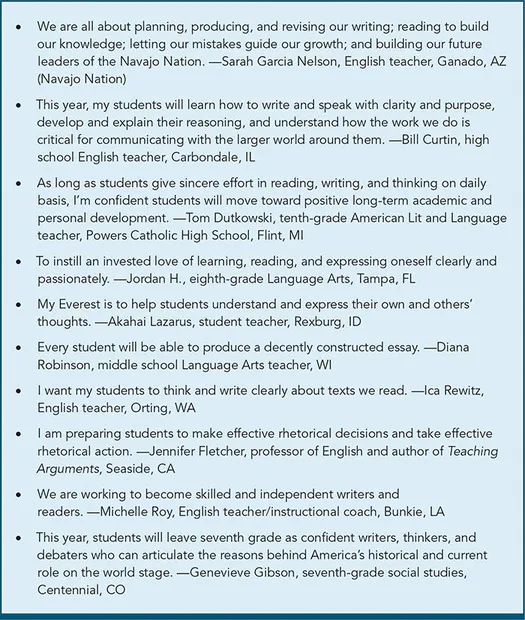

So just do this: put that Everest sentence you just wrote somewhere you’ll be forced to revisit for a few days, weeks, or months. Rewrite it from memory the next time you find yourself in a less-than-mission-critical meeting or presentation. And eventually, plaster it on your wall somewhere, introduce it to students, and tell them that this is what we’re ultimately after this year—this is what we do. Figure 1.3 shows a sampling of the Everest statements I’ve collected over the years when doing this exercise with teachers around the United States.

The better, saner teaching life starts with a personally crafted, well-articulated, highest-level objective.

Figure 1.3 • Sample of Real Teachers’ Everest Statements

Long-Term Flourishing: The Peak of Peaks

We can’t stop there, though. If all we do is define our work ourselves, we could easily justify “teach with your door closed,” isolationist approaches to our work. Such “Everest Island” approaches concern me. Education has plenty of Lone Rangers and not enough high-functioning teams. Early in my career, my “strategy” was the “Teacher as Savior” approach: be like the guy or girl in whatever Hollywood teacher movie I had recently seen, defy the many forces arrayed against my students and me, and single-handedly produce the glorious, odds-defying results of above-average standardized test scores.

This is a foolish waste of the change potential of our careers.

Our work is only a slice of what schools are for. So what, in a single sentence, is education about? What is its ultimate objective?

The answer is long-term flourishing. Long-term flourishing is broad enough to allow for each of our kids’ uniqueness and substantial enough to actually mean something: Rachel may flourish as an auto body technician and car enthusiast, whereas Rashad will flourish as a member of his church and a police officer, while Saylor isn’t sure what her future holds except that it’s got to include reflective writing and persistent self-improvement (see the Words Matter sidebar).

Let’s face it: none of us got into teaching for the impact we can make as measured by an end-of-the-year test; all of us got into it for the tiny contribution we hope our work can make to the life outcomes of our students, twenty years from now. Want to know how this school year is going for me? Ask me in a few decades when I bump into this year’s students at the grocery store and find them to be middle-aged, responsible, and contributing professionals or technical workers or parents or spouses or citizens. Did my work contribute to them realizing their potential, albeit in a small, unmeasurable way? Was I 0.01 percent of the reason that things have turned out well for them? Then it was a good year when I taught them; I did good work.

Words Matter

Long-Term Flourishing

Long-Term Flourishing

Long-term flourishing is the first principle of education. Before we espouse our philosophies or techniques or strategies or approaches, we must all agree that what we’re after is the long-term flourishing of young people. I say long-term because we became educators in hopes that our work might ripple—not just to the end of this school year but also to far beyond the end of what we can see.

And I say flourishing because it’s clearer, less subjective than success. In an era of internet-fueled comparisons, success is an ever-rising bar. There’s bound to be someone on Facebook or Instagram who is prettier than me, has more followers than me, lives in a better place than me, or has a cooler job than me. But there’s plenty of room for us all to flourish. That’s what I want for my students: long-term flourishing. It’s my job to boost their chances of experiencing that.

But do you see how painfully immeasurable this long-term view on teaching is? That’s the second way that our work is so much more challenging than Hillary and Norgay’s was: they knew when they were done, and you and I don’t. There was no ambiguity to whether or not they had achieved their goal, no room for debate. But for us, there are thirty or more Everests in view during every class period. Long-term flourishing is realized on a life-by-life basis, and it takes a full look of the womb-to-tomb journey for each student before we can know whether it’s happened. There’s no pretending: measuring the true impact of our work as teachers isn’t simple, no matter what the policies or evaluation rubrics say. And please know that even as I write this paragraph, I, as a practicing teacher in a public high school, also feel the pain of it.

At any rate, with both this universal Everest of long-term flourishing and our personally drafted Everest definitions in view, we now must move into more immediate, but not more practical, realms. The distinction between immediacy and practicality is important. Too often, I find myself falling into believing that if something isn’t immediately applicable to my work as a teacher, then it’s not practical. But learning how to think is imminently practical. That is what long-term flourishing and defining Everest help us do: they help us think more clearly. In this way, nothing is more practical than the long-term flourishing of young people. When compared to the goal of long-term flourishing, it’s standardized tests and grading systems that are impractical....