![]()

CHAPTER ONE

Origins

While formal organizations aimed at securing LGBT political and legal equality were rare prior to World War II, there were transnational dimensions of LGBT advocacy long before then. In the nineteenth century, as distinct homosexual subcultures were emerging in London, Paris, Amsterdam, and New York,1 a handful of Europeans challenged entrenched ideas about homosexuality and began calling for the decriminalization of same-sex sexual activity. News of their work spread internationally and sparked transatlantic connections among like-minded intellectuals.

At the same time, the rise of imperialism and the emergence of a new medical model of homosexuality contributed to escalating repression of gay activity and identity. Great Britain imposed laws mandating harsh penalties on same-sex sexual activities in its colonies throughout the world. Medical authorities argued that homosexual behavior stemmed from physical and mental abnormalities, creating new anxieties about same-sex attracted men and women already widely viewed as sinful and criminal. A series of highly publicized scandals exacerbated fears of a growing homosexual subculture threatening social order. But state persecutions of gay men like the 1895 trials of Irish writer Oscar Wilde also increased gay visibility and inspired the first international gay rights organizing efforts. Then, as now, movement toward more accepting views of homosexuality and decriminalization of homosexual behavior coexisted with fierce condemnation of same-sex attraction and severe legal, political, and social punishment of those confirmed or perceived to be gay.

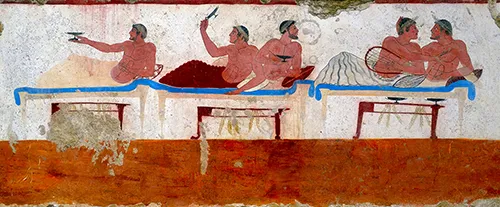

IMAGE 1.1 A depiction of same-sex love among the ancient Greeks on a fresco in the Tomb of the Diver, in what is now southern italy and created in approximately 475 BC.

Attitudes about homosexuality changed dramatically from ancient times to the latter 1700s. Ancient Indians, Chinese, Egyptians, Greeks, and Romans tolerated homosexual practices. With the rise of Judaism, Christianity, and Islam, acceptance morphed into denunciation in many places. The Torah’s Book of Leviticus contained two passages widely interpreted as negative references to homosexual acts. Leviticus 18:22 declares: “Thou shalt not lie with mankind, as with womankind; it is detestable.” Leviticus 20:13 reads: “And if a man lie with mankind, as with womankind, both of them have committed abomination; they shall surely be put to death; their blood shall be upon them.” These Jewish edicts informed early Christian interpretations of the story of Sodom and Gomorrah found in the Bible’s Book of Genesis. Where Jewish writings depicted the divine destruction of the cities as retribution for the people’s immorality and inhospitality toward Lot and his heavenly guests, Christian writers viewed homoeroticism as the sin that sparked God’s wrath. The biblical story of Sodom and Gomorrah is also told in the Qur’an and male homosexuality is denounced in Sura 4:16: “If two men among you are guilty of lewdness, punish them both. If they repent and amend, leave them alone; for God is Oft-returning, Most Merciful.” Unlike the Old Testament, the Qur’an did not call for homosexual behavior to be punished by execution. However, certain hadiths—sayings attributed to the Prophet Muhammad written almost two centuries after his death—described homosexuality as a profound “insult” to Islam meriting death by stoning.2

Despite these contested interpretations of the “sin of Sodom,” codes making same-sex sexual activities crimes punishable by death or castration spread throughout Eurasia and into Africa. The legal definition of sodomy varied. Sometimes, it was limited to anal penetration of a man to the point of ejaculation. It did not always include oral sex, but some codes encompassed nonprocreative sex acts, regardless of the gender (and, sometimes, the species) of those involved. However, many indigenous societies in the Americas, sub-Saharan Africa, and the South Pacific accepted same-sex intimacy and in some cases, even celebrated those who defied gender norms.3

Following Henry VIII’s break with the Catholic Church, English royal courts took the place of ecclesiastical courts in punishing sodomites. The Buggery Act of 1533, England’s first sodomy law, did not define it, but punished with execution “the detestable and abominable vice of buggery committed with mankind or beast.” The law targeted specific nonprocreative sexual acts, not specific groups of people. Preferring to handle legal matters through ecclesiastical courts, Mary I had the law repealed in 1553 when the jurisdiction of the Catholic Church was restored. Nine years later when Elizabeth I gained the throne, Parliament reenacted it, but it was not consistently enforced thereafter. In 1716, Rex v. Richard Wiseman defined heterosexual sodomy as a crime under the Buggery Act, but in 1817 Rex v. Samuel found that an adult man who performed fellatio on a boy did not violate the act. Eleven years later, as part of Prime Minister Robert Peel’s plan to codify English criminal law, Parliament strengthened the 1553 anti-buggery law by dropping the requirement for proof of “the actual emission of seed” and making “proof of penetration only” sufficient grounds for conviction. It also added the law to the criminal codes of the East Indies and Ireland. Although the last executions for buggery in England occurred in 1835, it remained a capital offense in England, Wales, and Ireland until passage of the Offenses against the Person Act in 1861.4

Invoking biblical injunctions against “crimes against nature,” civil and religious authorities led antisodomy campaigns in several Italian cities in the fifteenth century and across Spain in the sixteenth century. In 1553, Portugal’s new Office of Holy Inquisitor broadened the legal definition of sodomy to include the anal penetration of either a man or a woman and the penetrator as well as the receiver. If found guilty, violators could be burned at the stake, have their property seized, or be deported and sentenced to hard labor in Brazil, Africa, or India.5 When the French, Spanish, Dutch, and English first settled in North America, virtually all of their colonies outlawed male same-sex sexual activity and attempted to impose European sexual norms upon indigenous peoples as a means of “civilizing” them.6 Authorities also began to prosecute men and women who defied gender norms. In the 1690s, Massachusetts became the first American colony to outlaw crossdressing.7 In the late seventeenth century, authorities in London, Paris, and Amsterdam periodically attempted to quash their emerging sodomitical subcultures through surveillance, arrests, and prosecutions. Throughout this era, Catholic and Protestant reformers alike condemned sodomy, sex outside of marriage, masturbation, and oral sex. Those found to have engaged in these behaviors faced harsh penalties including fines, imprisonment, whipping, stoning, disfigurement, branding, pillorying, dismemberment, execution, and execution followed by dismemberment.8

Authorities rarely prosecuted women who had sex with women. England’s Buggery Act of 1533 did not mention lesbian sex. Indeed, few people of the era could conceive of sex that did not involve penile penetration. Trials of women charged with sexual offenses with other women were rare and usually involved women who had adopted male personas through crossdressing—seen as a dangerous threat to patriarchal ideals. But legal and religious records only tell part of the story. Women of this era expressed deep emotional ties to one another in letters, poetry, literature, and music. Some unmarried women shared households. Undoubtedly, some of these relationships were also sexual and the term “lesbian” was first used by the English in the 1730s, more than a century before the term “homosexual” was coined in Europe. But while lesbian sex was not illegal and same-sex intimacy between women was acknowledged, it was not condoned.9 In 1740, when the Qing dynasty banned consensual homosexual sex between men and homosexual rape in China, the law’s omission of women reflected male-centered Taoist notions of sex and a patriarchy that rendered women’s sexuality invisible, not a tacit acceptance of lesbian relationships.10

In the late eighteenth century, the Enlightenment triggered a major shift in attitudes toward private sexual behavior. Frederick the Great of Prussia and Joseph II of Austria argued that “individuals should be free to believe, think, and even act as they wish, consistent with the rights of others, the maintenance of public order, and the ultimate authority of the state.” Upon succeeding his father Frederick William I, Frederick the Great—possibly because of his own sexual inclinations—ended antisodomy crackdowns on taverns and male brothels in Berlin. He did not, however, repeal antisodomy laws. In France, Voltaire, Montesquieu, and other philosophes denounced sexual licentiousness and deviant practices like sodomy, adultery, and prostitution, but not on religious grounds. Bitterly critical of organized religion, the philosophes framed their objections to sexual deviance not in moral terms, but based on the view that sexual vice destabilized social order. In an age of frequent war and increasing economic competition, the philosophes deemed population growth essential to national prosperity and security. They therefore condemned nonprocreative sexual activities like sodomy. But they were even more critical of the state’s brutal treatment of those convicted of sexual deviance.11

A leading French philosophe, the marquis de Condorcet, took this argument to its logical end and advocated the decriminalization of sodomy. He wrote: “Sodomy, so long as there is no violence, cannot be covered by criminal law. It does not violate the rights of any other man. It only exercises an indirect influence on the good order of society, like drunkenness and gambling.” While he echoed his contemporaries in calling sodomy “a low vice, disgusting,” he argued that the appropriate punishment was “contempt,” not imprisonment or far harsher state-sanctioned penalties.12

In contrast to his French contemporaries’ brief commentary on sexual deviance, British philosopher Jeremy Bentham wrote volubly about the subject. The founder of utilitarianism, Bentham wrote the longest essay on sodomy produced in the eighteenth century and the longest one written in English until the late nineteenth century. Although he chastised himself for worrying that publishing his work would destroy his professional reputation, Bentham chose not to release his essays on sodomy. They were not published until 1978, nearly two hundred years later.

In a 1785 essay, Bentham raised—and then demolished—all of the conceivable objections to pederasty, a synonym for sodomy without the religious condemnation imbued in the latter term. In response to Montesquieu’s claims about the debilitating impact of sexual deviance, Bentham pointed to the power of ancient Greeks and Romans who engaged in same-sex sexual activities. Because he believed that people with exclusively same-sex sexual lives comprised only a small portion of the population, Bentham scoffed at French philosophe Voltaire’s fears that sexual deviance would inhibit population growth. In response to claims that pederasty threatened marriage, Bentham argued that adultery posed a far bigger danger. Bentham dismissed outright the notion that sodomy was a “crime against nature,” asserting “If a pleasure is not a good, what is life for, and what is the purpose of preserving it?”13

Bentham stressed that punishing pederasty, not practicing it, was what harmed society and individuals. He warned that penalizing sodomy would radicalize those convicted and make them more, not less, likely to reengage in sexual deviance. Criminalizing behavior simply because a majority found it offensive could slide into tyranny. The mere existence of antisodomy statutes, Bentham claimed, created opportunities for extortion, blackmail, and fraudulent persecutions. He articulated many of the arguments still successfully used to justify the decriminalization of consensual homosexual relations between adults.14

While Bentham kept his views private, there were others who publicly called for the liberalization or abolition of statutes on moral offenses. In 1780, after an Englishman convicted of attempted sodomy choked to death during a pillorying witnessed by a vicious mob, Edmund Burke, a conservative member of the Whig Party, implored his colleagues in the House of Commons to abandon such barbaric punishments. Burke got some support in Parliament, but the press lambasted him for expressing sympathy toward a sodomite. Harsh physical penalties for sodomy remained British law for decades afterward.15

The Enlightenment’s focus on individual rights and freedoms triggered more immediate change elsewhere. In the aftermath of the American Revolution, several US states reformed their legal codes. Thomas Jefferson failed to convince the Virginia legislature to make castration the penalty for sodomy instead of execution. In 1777, Georgia also rejected a call to make sodomy a noncapital crime. But ten years later, Pennsylvania opted to punish sodomy with imprisonment, not death. In 1796, New York and New Jersey made similar reforms and Massachusetts (1805), New Hampshire (1812), and Delaware (1826) soon followed.16

In revolutionary France, calls for liberalization also yielded major changes in antisodomy laws. In 1791, fueled by expansive notions of individual rights and no longer bound by prerevolutionar...