![]()

SECTION I

Fundamentals

The Value of Progress Monitoring

The first four chapters of this book provide background information about the importance of progress monitoring (PM) of students’ growth. Assessment of teaching and learning and of academic, behavioral, and functional skills are considered, with PM at the center of those discussions.

In Chapter 1, PM is defined. A synthesis of the research supporting PM in a variety of academic, behavioral, and functional areas is presented as evidence for its use. PM is a form of single-case–designed research, which is further explained.

Building on the underpinnings established in Chapter 1, Chapter 2 presents information about the use of PM in foundational academic skills: basic reading, writing, and mathematical fluency. Practical reasons for selecting fluency-based PM are discussed. The major commercially available measures are introduced, alongside a discussion of their technical adequacy that establishes why they should be used. As well, practical considerations of how to select, administer, and score PM measures are shared.

The third chapter of the section applies PM concepts to data collected about students’ social or behavioral performance. As most teachers are aware, children who exhibit behaviors such as verbal or physical aggression, tantrums, or running away from class need to have their challenging behaviors addressed so that the children can better integrate in the classroom and community. Collecting data on the frequency or duration of such behaviors and using it for PM can inform teachers and specialists about whether behavior interventions are effective.

Chapter 4 considers the ways in which task analysis, a method by which a larger task or skill is broken into its sequential steps, can be used not only to collect data on how independently a student is performing a task but also to monitor his or her progress toward independence. Task analysis is commonly used to teach and assess functional skills such as hand washing or using public transportation, but it can also be implemented in teaching complex reading comprehension strategies or higher level math algorithms.

Taken together, the four chapters in the first section provide the background information you need to decide what to progress-monitor. You will be able to collect the materials you need and prepare to begin your PM journey with the help of the directions provided in Section II.

![]()

CHAPTER 1

Introduction to Progress Monitoring

LEARNING GOALS

After reading this chapter, you will be able to

•Define the term progress monitoring in the context of teaching and learning.

•Summarize the research-based foundations of progress monitoring.

•Identify practical applications of progress monitoring.

•Recall research that supports using progress monitoring in reading, mathematics, writing, and functional or social skills.

•Compare progress monitoring to single-subject research designs.

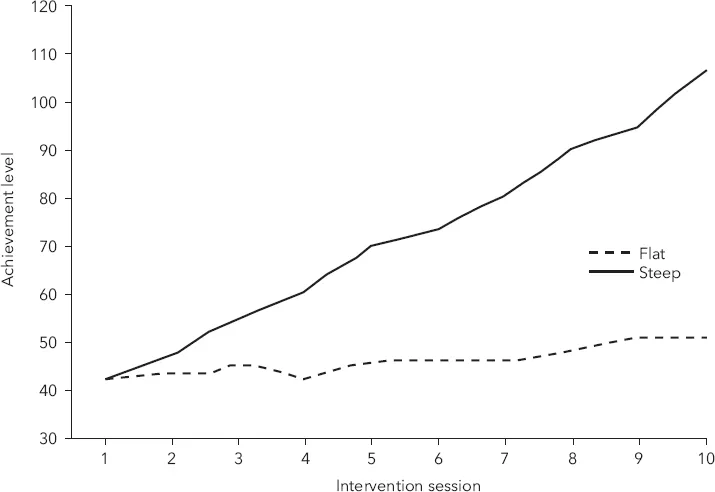

People who teach, coach, or provide therapy to students or clients may wonder whether their charges are making progress at an appropriate rate. To what extent is the selected instruction or intervention effective in helping an individual meet his or her goals? In special education, with annual individualized education program (IEP) reports and goals looming, the teacher or specialist needs to determine whether the student's learning trajectory will meet or exceed the goal. General educators also need to keep track of whether students will meet end-of-year learning goals, ensuring that their instruction is preparing the children for the next grade. On the one hand, if the learning curve is too flat, indicating that learning is occurring at a slow rate, as in Figure 1.1, the professional needs to change instruction in some way so that the student gets back on track. On the other hand, a steep learning slope, also illustrated in Figure 1.1, shows that the student is learning rapidly, which may mean that goals will more readily be met and that instructional methods are adequate. Relying solely on summative assessments, such as final evaluations or end-of-chapter tests, may result in failure to meet goals because these assessments do not provide clues that trouble is brewing until it is too late to remedy the problem. Formative assessments, those that are conducted on an ongoing basis, will reveal the slope of the child's learning curve. Progress monitoring (PM) is a well-developed and extensively researched method of formative assessment.

This book considers PM from three perspectives: 1) improving students’ fluency in basic academic skills, 2) tracking and changing students’ behaviors to be more prosocial, and 3) helping students make progress toward complex academic and functional goals via a process called task analysis. Fluency, or quick and accurate performance in certain focused academic skills, is the foundation of performance on more complex academic work and thinking (Deno, 2014). Examples include orally reading text with accuracy and with appropriate rate and expression, solving basic math facts, or free writing sentences with ease. Teachers wishing to build the basic academic ability of their students will appreciate PM for its ability to assess and inform classroom instructional methods. Many kinds of disruptive or harmful behaviors can be tracked and analyzed with the goal of decreasing student engagement with those behaviors and increasing the use of prosocial ones. Functional skills, such as hand washing or using public transit, as well as complex academic strategies, such as approaches to building reading comprehension or tactics for writing a persuasive essay, can be progress-monitored through task analysis. (This process, which involves breaking down complex goals or tasks into a series of discrete steps, is discussed in depth in Chapter 4.)

Figure 1.1. Examples of flat and steep growth lines.

Because PM can measure both fluent performance on academic skills and advancement along complex steps of a task or strategy, it is an incredibly flexible and useful tool for special educators, related services professionals (e.g., speech-language pathologists, occupational therapists), and general education classroom teachers. We can use PM procedures to benefit individuals of all ages, whether we are observing a baby making the transition from crawling to standing to walking, or tracking the weight maintenance goals of an older adult in an assisted living environment. We can monitor the level of independence with which a teenager with intellectual disability can prepare her own breakfast or the quick, accurate reading performance of a 6-year-old who is just developing literacy skills. We can observe and progress-monitor the gains made by a young adult with autism in initiating a social interaction as well as the persistence of a social 12-year-old in keeping his attention on his work rather than playing with his friends.

Once you have mastered the essential components of PM, you will be able to keep track of nearly any conceivable skill, behavior, or accomplishment your students or clients are pursuing. You will be able to select your lessons more precisely and align them with the needs of your students, which will yield more effective instruction that leads to mastery more quickly. PM is not a miracle, but it is a powerful tool for teachers and specialists who are working with a diverse array of individuals.

PROGRESS MONITORING IN CONTEXT: OVERVIEW OF ASSESSMENT TYPES

To understand how PM developed and the purposes for which it can be used, it is helpful to examine PM in the context of other types of assessment. This section briefly reviews different ways assessment is used in educational and therapeutic settings and how PM has evolved since the 1980s.

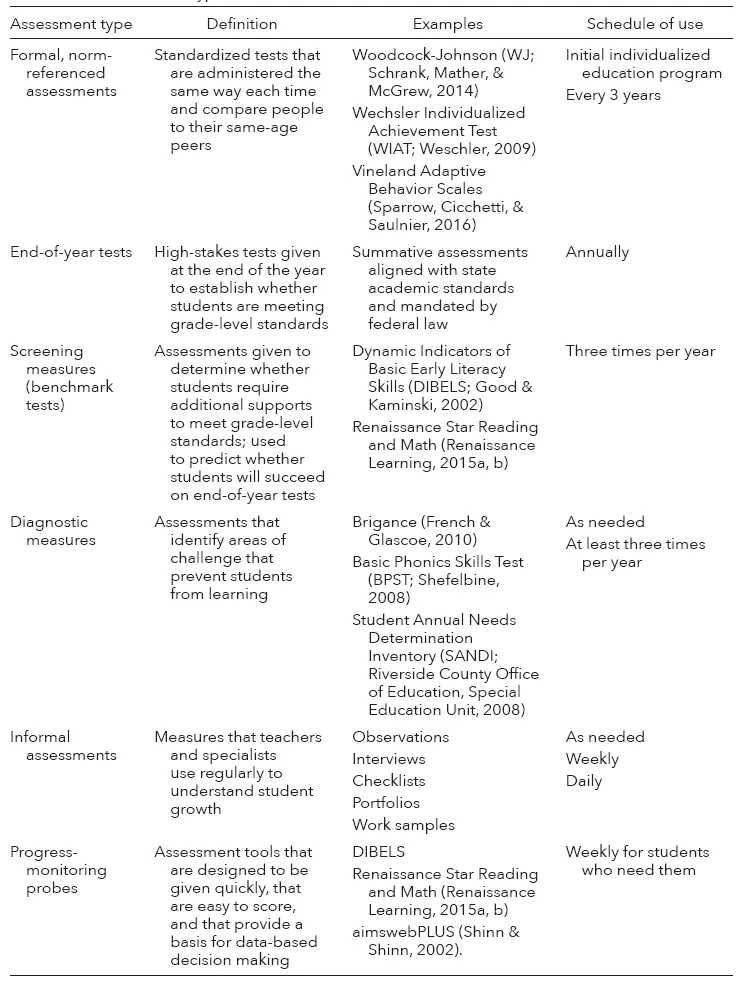

Educators and professionals in related services use several types of assessments for different purposes, as summarized in Table 1.1. As discussed previously, assessments can be summative (measuring what has been learned) or formative (measuring ongoing learning or progress for the purpose of making changes to increase success). They can be formal standardized tests, such as state high school proficiency exams, or less formal, nonstandardized measures, such as chapter tests in social science classes or final exams in algebra. Informal assessment also includes observations of student behavior or performance, interviews with families to learn more about a student's preferences, portfolios of student work, and video capture of a student engaged in a functional task.

Some assessments are mandated by the federal or state government, such as high-stakes end-of-year tests designed to determine whether students met grade-level standards. Teachers spend significant time preparing students for these tests, the results of which are used to evaluate whether schools are effective. As well, the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA, 2004), the federal special education law, requires that students with disabilities be assessed annually, to ascertain whether they are achieving their IEP goals, as well as triennially, to determine whether they continue to qualify for special education services.

There are other assessments that school districts and school sites insist on. School administrators may insist on a battery of benchmark testing each trimester to evaluate whether students are at grade level or struggling to learn. These assessments are often used to place students into groups in which they can receive interventions that will help them catch up to their peers.

Beyond this, there are assessments that teachers use to assign grades to students. Teachers may use grade books to track whether students turn in homework, to record the grades students earn on essays, and to monitor students’ scores on group projects. These grades are entered on report cards that are then sent to families, students, and even colleges.

Perhaps the most important assessments teachers and specialists use are the informal ones that help them understand what their students’ strengths are and the areas where students need more strategic intervention. Phonics screeners, math facts tests, checklists of social skills, language samples, and work products are just of few of the multitude of tools that teachers regularly use with their students. These measures are used to evaluate whether students are learning as well as what skills need to be taught next. PM is one kind of informal assessment that teachers might choose.

Table 1.1. Assessment types and schedules

FOUNDATIONS: PROGRESS MONITORING AND CURRICULUM-BASED MEASUREMENT

PM is a particular kind of informal assessment. It was designed to be easy to use, and it is a powerful tool in refining instruction for struggling learners. To better understand PM, let's examine its roots in curriculum-based measurement (CBM).

PM draws from work in CBM that dates back to the late 1970s. Researchers, concerned that teachers were making instructional decisions based on unreliable or infrequent tests, which made their instruction less effective, sought methods to institute more focused data-based decision making. The earliest forays into CBM were in reading fluency, although researchers also explored spelling and writing (Deno, 1985). These tests, created by teachers and drawn directly from the curriculum in use in the classroom, were an informal method of assessment designed to be administered, scored, and analyzed simply and quickly (Deno, 2014). The results of CBM assessments were graphed and used to plan instruction for individual students, with positive results for student learning (Marston & Magnusson, 1985; Marston, Mirkin, & Deno, 1984). In short, CBM has three primary goals: 1) measuring the effects of instruction on a particular child's learning, 2) permitting teachers to make data-based decisions on whether instructional changes are needed, and 3) creating more robust educational programs for each child (Fuchs, 2017).

From the beginning, CBM was bound with the idea of PM. With multiple short probes designed to be equally difficult (Fuchs, 2017), CBM tools were meant to be administered frequently; their results were supposed to be tracked over time and used to evaluate the effectiveness of instruction (Deno, 1985; Marston & Magnusson, 1985). Evidence-based practices (EBP) are statistically effective instructional strategies for most students, but an individual practice may not be useful for the child who is sitting in front of you right now. CBM (or PM) is a way to test instructional hypotheses about whether an EBP is right for a particular person; it can be used to ensure that the instruction a teacher provides is reaching each student (Espin, Wayman, Deno, McMaster, & Rooij, 2017).

Over time, researchers began to develop more general measures of skills and abilities that were unrelated to any specific classroom curriculum. In this way, school district personnel were able to adopt assessments that would cover expected grade-level skills, regardless of whether particular instructional passages were used. The Dynamic Indicators of Basic Early Literacy Skills (DIBELS; Good & Kaminski, 2002) was an early commercially available measure that was designed to be easy to use, efficient, and cost effective as well as reliable and valid for measuring what it purported to measure (University of Oregon, Center on Teaching and Learning, 2020). A measure is reliable when it obtains consistent, stable results and valid when it truly assesses what it is intended to assess. The concepts of reliability and validity are discussed further in Chapter 2.) Math measures such as Accelerated Math were developed by the early 2000s, at which time researchers referred to CBM and PM interchangeably (Ysseldyke & Tardrew, 2007). These measures alleviated issues that teachers and districts faced when they attempted the difficult work of developing their own sets of tools (Deno, 2014). These measures include such tools as DIBELS (2002) or aimsweb 2006), along with others described in Chapter 2.

Academic PM is conducted with quick, short measures, many of which can be administered in 5 minutes or less (Deno, 1985; Kaminski & Good, 1996). An oral reading fluency measure administered to an individual student for 1 minute, a math facts assessment in which students get 5 minutes to solve addition and subtraction problems, or a writing prompt in which students are given 3 minutes to write as many words as they can, are the sorts of academic PM tools that are widely available. Because these PM tools measure fluency, or how quickly students can complete the task, they are best suited to measure concrete or foundational skills; other measures are better for more complex thinking, such as reading comprehension (Fuchs & Fuchs, 1992). PM measures have great appeal and utility for teachers who are anxious to help their students reach their learning goals.

PROGRESS MONITORING APPLICATIONS

PM is perfectly suited for many applications. This book primarily discusses PM...