eBook - ePub

Seven Events That Shaped the New Testament World

Carter, Warren

This is a test

Compartir libro

- 184 páginas

- English

- ePUB (apto para móviles)

- Disponible en iOS y Android

eBook - ePub

Seven Events That Shaped the New Testament World

Carter, Warren

Detalles del libro

Vista previa del libro

Índice

Citas

Información del libro

This useful, concise introduction to the worlds around the New Testament focuses on seven key moments in the centuries before and after Jesus. It enlightens readers about the beginnings of the Christian movement, showing how religious, political, and economic factors were interwoven in the fabric of the New Testament world. Leading New Testament scholar Warren Carter has a record of providing student-friendly texts. This introduction offers a "big picture" focus and is logically and memorably organized around seven events, which Carter uses as launching pads to discuss larger cultural dynamics and sociohistorical realities that were in some way significant for followers of Jesus and the New Testament. Photos and maps are included.

Preguntas frecuentes

¿Cómo cancelo mi suscripción?

¿Cómo descargo los libros?

Por el momento, todos nuestros libros ePub adaptables a dispositivos móviles se pueden descargar a través de la aplicación. La mayor parte de nuestros PDF también se puede descargar y ya estamos trabajando para que el resto también sea descargable. Obtén más información aquí.

¿En qué se diferencian los planes de precios?

Ambos planes te permiten acceder por completo a la biblioteca y a todas las funciones de Perlego. Las únicas diferencias son el precio y el período de suscripción: con el plan anual ahorrarás en torno a un 30 % en comparación con 12 meses de un plan mensual.

¿Qué es Perlego?

Somos un servicio de suscripción de libros de texto en línea que te permite acceder a toda una biblioteca en línea por menos de lo que cuesta un libro al mes. Con más de un millón de libros sobre más de 1000 categorías, ¡tenemos todo lo que necesitas! Obtén más información aquí.

¿Perlego ofrece la función de texto a voz?

Busca el símbolo de lectura en voz alta en tu próximo libro para ver si puedes escucharlo. La herramienta de lectura en voz alta lee el texto en voz alta por ti, resaltando el texto a medida que se lee. Puedes pausarla, acelerarla y ralentizarla. Obtén más información aquí.

¿Es Seven Events That Shaped the New Testament World un PDF/ePUB en línea?

Sí, puedes acceder a Seven Events That Shaped the New Testament World de Carter, Warren en formato PDF o ePUB, así como a otros libros populares de Theology & Religion y Biblical Studies. Tenemos más de un millón de libros disponibles en nuestro catálogo para que explores.

Información

Categoría

Theology & ReligionCategoría

Biblical Studies

He didn’t tag himself Alexander the Great, but certainly history has come to know him as that. Two thousand years later he is still known as “the Great.” He died on June 10, 323 BCE, only thirty-three years old. He was conqueror of much of the known world at an age when many of us have not yet figured out what we want to be when we grow up.

Was he really great? And why begin a book on the New Testament and the early Jesus movement with his death in 323 BCE? That’s some three centuries before Jesus’s ministry. There were no churches and no Jesus-followers in Alexander’s time. With three centuries dividing them, what does Alexander have to do with Jesus and the early Jesus movement? That’s the big question I want to think about in this chapter.

Alexander was an overachiever. He was king of Macedonia for thirteen years, from 336–323 BCE.[2] He conquered the world’s leading superpower, Persia, and established an empire that stretched from Greece in the west, to India and Afghanistan in the east, and to Egypt in the south. He was a king, a general, a warrior, a world conqueror. He was also a party boy, a heavy drinker, bisexual, capable of violent temper tantrums, and paranoid.

Alexander casts a huge shadow. He’s the sort of man of whom legends are born, in his own time and ever since. He has multiple personalities and a lengthy afterlife through the millennia. In our own time, Oliver Stone’s movie Alexander (Warner Brothers, 2004) is a case in point. As with other key figures in history such as Jesus and Paul, it can be difficult to separate fact from legend and to figure out exactly what he was about. Will the real Alexander please stand up?

We’ll start by outlining his kingly-soldierly career, next take up the question of why he might matter for the early Jesus movement, and then contemplate the notions of greatness and manliness that he was said to exemplify.[3]

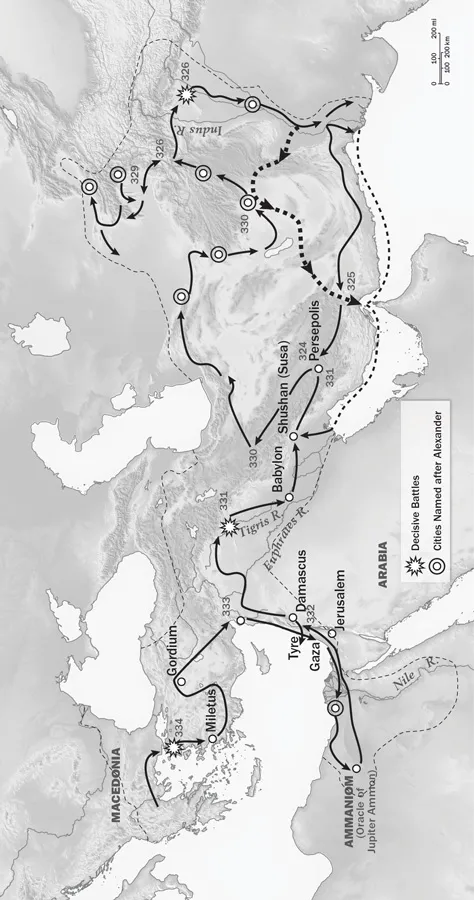

Figure 1.1. Map of Alexander’s battles, travel, and empire (Source: Bible History Online)

Alexander’s Résumé

Who knows what events Alexander would have chosen for his own résumé? I’ll suggest the following:

- Alexander was born in northern Greece in late July of 356 BCE to Philip II, king of Macedonia, and his fourth wife, Olympias. Philip had unified Macedonia and led it in a resurgence of military, political, and economic power among the states of mainland Greece.

- But with Alexander nothing is simple or unambiguous, especially not his birth. Legends developed about his superhuman origins. One tradition claimed that his ancestors included the superhero Heracles, son of the supreme god Zeus, as well as Achilles, the military hero of the Trojan wars. Heracles was the ultimate strongman and model of macho masculinity (Diodorus Siculus, Hist. 17.1.5). Another tradition asserts that because a serpent was observed lying next to Alexander’s mother, Olympias, Philip stopped having sex with her, thinking that her partner was a divine being. The implication is that Alexander’s conception involved divine intervention (Plutarch, Alex. 2.4). Through his life, Alexander increasingly seems to claim a divine identity. Such legends present him as a superhero.

- As a youth, Alexander studies subjects such as philosophy, rhetoric, and geometry under the famous philosopher Aristotle. As a budding warrior, he learns war in his father’s army against a coalition of Athenian and Theban armies.

- At the age of twenty in 336 BCE, Alexander becomes king after his father, Philip, is murdered. The murder is bad enough, but it happens, unfortunately, at his daughter’s wedding. Why does his murder happen? Nothing is straightforward. One rumor has it that Alexander’s mother incited the murder to ensure that Alexander becomes king. Another rumor attributes the assassination to the Persians, who fear Philip’s imminent military campaign against them.

- Alexander inherits his father’s plan to attack the Persian (or Achaemenid) Empire. Perhaps this plan avenges previous Persian aggression against Greek states. At least it seeks to free Greek cities in Asia Minor. Alexander seems to understand this to mean the conquest of the whole known world. This project will occupy him for the rest of his life. He does not sit at home and send his troops away on lengthy campaigns. Alexander literally leads his army and its support team (including philosophers, poets, scientists, and historians) across thousands of miles and into battle for the next eleven years. He does not return to Macedonia.

- In 334 BCE, his army, estimated to number some 30,000 foot soldiers (including archers and javelin throwers) and 5,000 cavalry, crosses from Macedonia into Asia Minor (modern Turkey) across the Hellespont, the narrow strip of water that divides Europe (the West) and Asia (the East).

- He wins several major battles over Persian forces, first at the Granicus River in northwest Asia Minor in 334 BCE, and then in 333 BCE at Issus, the crossroads of Asia Minor and northern Syria. The Persian king Darius III escapes, though Alexander captures Darius’s mother, wife, and children.

- In 332–331 he heads south and gains control of Syria and Palestine. Egypt surrenders without a battle. He is proclaimed a pharaoh and son of the Egyptian god Osiris. In 331 he founds the city of Alexandria, which he names after himself and is one of numerous cities bearing his name. The city flourishes and, with Rome and Antioch in Syria, becomes one of the three largest cities of the Roman Empire.

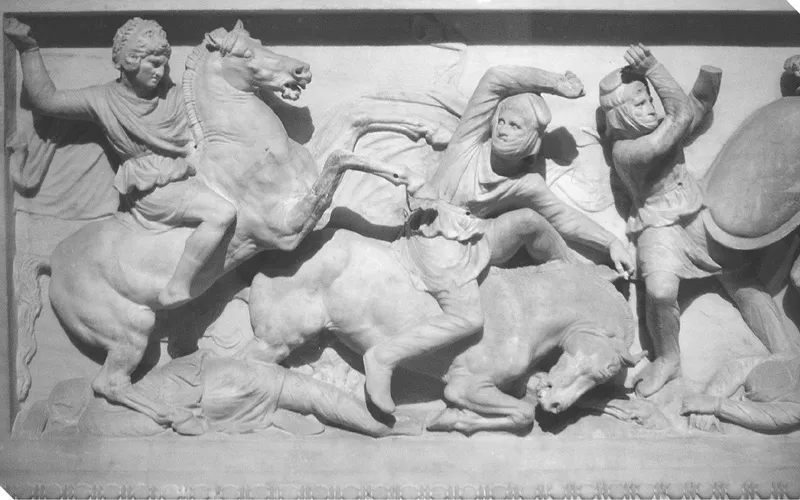

Figure 1.2. Sarcophagus with a depiction of Alexander fighting the Persians. (Wikimedia Commons)

- Southwest from Alexandria, he visits the famous oracle of Ammon (or Amun) at Siwah Oasis (in the desert of Egypt, near the present Libyan border). Legend has it that the oracle identifies him as the son of Zeus-Amun. Subsequently he seems to understand himself to be divine, an understanding that will become increasingly controversial. Being identified as divine was a way of recognizing his great power and rule and his great benefactions of material favors.

- Alexander marches his army over a thousand miles to the northeast, into the center of the Persian Empire. For a third time he battles Darius, and he wins at Gaugamela on the Tigris River in 331 BCE. Again Darius, who seems to have incredible good luck, escapes.

- In 330 BCE Alexander loots and burns the Persian capital, Persepolis. Darius escapes again, but this time his luck runs out. He is assassinated by one of his own officials. Alexander avenges the king’s death by publicly executing the official, and he honors Darius by burying him in the tombs of the Persian kings. Alexander has gained great glory in defeating the mighty Persian Empire, dominant for over two hundred years. He now rules the Macedonian Empire. He tries to win Persian support by introducing Persians into his command structure. Alexander adopts Persian clothing and customs such as proskynēsis, a practice in which an inferior bows before a superior. Many Macedonians resist such practices. He executes some who are critical.

- During 330–327 he pacifies the eastern Persian Empire (eastern Iran) via much fighting.

- After marrying Roxana (Roxane/Roxanne), the beautiful daughter of a leading Persian, Alexander invades India. In 326 he defeats Porus, the rajah or king of Punjab in western India, at the Hydaspes River. Shortly afterward, his troops, wearied by and resentful of a campaign that never ends, revolt. They refuse to advance at the Hyphasis (now Beas) River. The thousands of miles of marching and of battle have taken their toll.

- The army turns back. By river, sea, and land, and with military actions along the way, Alexander heads westward to Susa, 160 miles east of the city of Babylon. At Susa in 324, Alexander organizes a mass, five-day wedding, Persian-style. Alexander marries two women, one of whom is Darius’s oldest daughter, Stateira. Some ninety of his leading officers marry Persian women.

- The army again revolts in resentment against Alexander’s attempts to include Persian troops. Alexander responds harshly in executing some of the leaders, and he increases the pay for loyal troops. At Opis on the Tigris River north of Babylon, he is also said to stage a sacrifice and banquet of reconciliation in 324, in which he prays for harmony between the Macedonians and Persians.

- Alexander plans to extend his empire south into Arabia. But in June of 323 BCE he becomes ill at Babylon, and he dies in the same year. Nothing is ever simple with Alexander. Did he get sick naturally (malaria?), or was he poisoned by one of his own men? Alexander’s body is taken to Egypt, supposedly for burial at the Siwah Oasis, close to his “father” Zeus-Amun; instead he is entombed in Alexandria.

- Despite all his wives, Alexander leaves no adult heir. Power struggles break out among his generals, but none initially prevails. Some fifty or so years later, by the 270s BCE, three kingdoms emerge as successors to Alexander’s empire and kingship until they give way before the next superpower: Rome. In one kingdom, Egypt, Ptolemy establishes a dynasty of kings (the Ptolemies) that lasts nearly three hundred years, until Cleopatra—yes, that Cleopatra—is defeated by the Roman Octavian in 31 BCE at the battle of Actium. Octavian becomes the first Roman emperor, known as Augustus. At its largest the second kingdom (of Alexander’s legacy) spans western Turkey to Afghanistan and is centered in Syria. It is ruled by the Seleucid dynasty of kings. Through the centuries, it loses territory in the west and east until the Roman general Pompey conquers what is left in Syria in 64 BCE. The third kingdom, Macedonia itself, is strongly disputed until 276 BCE, when Antigonus Gonatas establishes the Antigonid dynasty of kings, which rules for over a hundred years until Rome defeats it in 168 BCE.

Alexander Is Dead: So What?

This is but one telling of Alexander’s life. Since his own time there have been numerous retellings, numerous constructions of Alexander’s identity. The outline above selectively highlights his military-kingly accomplishments in defeating the Persian Empire and in building the Macedonian Empire. It does not include numerous other aspects of his life: his wounds suffered in battle; the high value he placed on friendship; his active sex life with females and males (including his male lover Hephaestion, who died in 324); his polygamy (tradition records three wives and a lover); his heavy drinking; his legendary superhorse Bucephalas, after whom he named a city in India (Bucephalia); his quick temper; his cold-blooded murder of close supporters (Parmenion, Philotas, Cleitus, Callisthenes); his generous spirit; his growing paranoia; or his increasing assertions of his divinity and the resulting debates.

Through it all, what was Alexander trying to accomplish? How do we make sense of his activity and accomplishments? Historians have wrestled with these questions and offered explanations variously emphasizing cultural, economic, and political motives. Was he, for example, trying to civilize barbarians with superior Greek culture? Or was he trying to establish a cosmopolitan world with a fusion of Western and Eastern cultures, the unity of humankind, and the common fatherhood of Zeus? Was he a pragmatist who sought to use the expertise and skills of local people to enhance his own (Macedonian) interests? Was he looking to take over the land and wealth of the Persian Empire first through booty and plunder, and then by taxes and levies, or was he seeking new economic interactions through settlement, trade, and access to resources? Was he, as leader of all the Greek states, set on military revenge against Persia for age-old violations against Greek states? Did he inherit such a mission from his father, and then set out to outdo his father? Or was he a man with a political vision to rule the world? Was he a man who liked the companionship and conquest of war?

We cannot evaluate these options here. Alexander, clearly, was not a simple man, and simple explanations fail in the face of his complexities. Some of these options, though, are immediately less compelling than others. The proposals that center on grand, all-embracing intentions such as civilizing barbarians, fusing cultures, creating economic order, and imposing political visions seem less convincing. Better explanations run along the various lines of Alexander’s personal quest for power, the satisfactions of contest and conquest (for whatever reasons), getting access to riches and resources from taxing Asia, and the pragmatic necessities of dealing with unfolding circumstances and negotiating competing and complex demands.

Spreading Hellenistic Culture

Whatever Alexander’s aims or intentions, more important for our purposes is the question of the impact of his endeavors. We’re back to that question: What does Alexander have to do with Jesus and Jesus-followers who live over three centuries after him?

A significant part of the answer has to do with the cultural forces that Alexander’s military conquests let loose in the ancient world, forces that reverberated across thousands of miles and hundreds of years. Military conquest is never just about military victory and defeat; it is also about cultural influence and interaction. Whatever his intentions, Alexander’s campaigns and armies, with their large supporting casts, set in motion the spread of Hellenistic culture throughout the territory he claimed.

Some historians have seen this process as the one-way spread of glorious Greek civilization over uncouth barbarians. No doubt some of the Macedonians thought like this, and it cannot be denied that Greek language and culture continued to be a major influence for centuries. But to see Alexander’s impact as a one-way street is inadequate, partly because it ignores the local cultures that were in existence long before and after Alexander’s time, and partly because it does not recognize that cultural interaction is a two-way street.

How did this spread of Hellenistic culture and its interaction with local cultures take place? Alexander’s résumé highlights several ways that continued through the following centuries.

People Presence

Physical presence and interaction with local peoples were one means by which Hellenistic culture spread. It’s impossible to march thousands of people through any geographical area without significant interactions with local people. Armies need food, shelter, supplies, equipment repairs, transportation, local knowledge, and recruits. The spread of Greek language, values, and practices, as well as the gaining of local knowledge, was inevitable as these personnel interacted with local peoples. Victories in battle not only establish control over territory, people, and resources; they are also coded with messages about cultural superiority and about more powerful gods. Religious syncretism resulted as local gods blended with Greek gods. In India, for example, post-Alexander statues of Buddha appeared presenting him like Apollo and wearing Greek clothing. Such people-to-people give-and-take would continue for centuries.

Local Alliances

Alexander also sought alliances with local peoples. He educated upper-status local young men in Greek language and ways. He included local Persian peoples in administering areas of his empire and admitted others to his army. He thereby utilized their skills and local knowledge while incorporating them into the sphere of Hellenistic culture. Intermarriages between Greeks and non-Greeks (Alexander married three local women) continued over subsequent centuries. Alexander’s journeys and mapping of routes not only opened up new worlds, but also provided opportunities for trade to develop.

Urban Development

Establishing cities was another major means of cultural impact and exchange. Traditions attribute to Alexander the founding of more than seventy cities, a number of which were named after him, such as Alexandria in Egypt. The number is inflated, but the importance it attributes to cities is not. It is said that subsequently the Seleucid line of his successors founded an additional sixty cities. Some cities were military outposts; others were settled by Greek colonists and veterans, along with local peoples, with primarily administrative and commercial purposes. Whatever their intent, cities functioned as centers of Greek language, culture, and political structures. For example, city constitutions established a council, public officials, and elections. Cities included Greek features like the agora—both a political gathering space and a commercial marketplace—and theaters. Institutions proliferated, such as the gymnasium, which was not a health club or basketball...