![]()

Chapter 1

Meeting the San Elders

In 2009 we visited the McGregor Museum in Kimberley, South Africa, to make a study of ancient organic artefacts from Border Cave. We found that many of the objects looked remarkably similar to items of historical San material culture, so we arranged the following year to study the century-old Fourie Collection of Kalahari San material culture housed at Museum Africa in Johannesburg.1 In addition to finding many parallels between the archaeological objects from Border Cave and items in the Fourie Collection, we discovered that even though many objects were identified in the catalogue of the collection, their function or meaning was unclear or unknown. We thought it a great pity that valuable information was lacking from this unique archive. Francesco had the idea of inviting San elders to the museum to discuss the items with us, and documenting their comments on film. In this way their knowledge of the objects, expressed in their own language, would be preserved; English subtitles would make their commentary accessible to viewers who did not understand the language they spoke. In our capacity as archaeologists, we would glean further information from them through question-and-answer sessions focused on items in the collection.

We thought that it would be best to have the input of two women and two men; one of the men should be a traditional hunter because hunting equipment is prevalent in the collection, and the other a traditional healer or shaman able to explain the meaning of esoteric objects. Although numerically objects related to hunting are more represented in the collection than objects used by both genders or only by women, they are all present in the collection, and in the literature more emphasis has traditionally been placed on hunting equipment than on domestic activities. We hoped that the women could inform us about objects related to typical female activities (bead production, cooking practices), but also about less touched upon categories, and give us a female view on typical male activities. Louis Fourie had gathered the objects from the Kalahari Desert, and it was therefore clear that the elders would need to come from this region, which today includes south-western Botswana and eastern Namibia. A filmmaker, Katherine Thompson-Gorry, was keen to document the discussions at Museum Africa. She also wanted to make a documentary film about one of the elders, which would record his journey from his home to Museum Africa in Johannesburg and back.

We decided to approach San elders in the villages of Kacgae and Bere, in the Ghanzi District in Botswana, as we had got to know the people there in the course of previous visits to the region. In December 2011, Lucinda and Kate Thompson-Gorry made a trip to these villages to present the project to four elders, a translator, and the chiefs of the villages. The elders agreed to collaborate on the project the following year, and accepted the invitation to work with us for ten days at Museum Africa. We made a second trip there in March 2012 to help the elders and the translator apply for their passports in Ghanzi, and to establish a memorandum of understanding regarding the conditions of their collaboration with us. On 13 June 2012 a research permit was issued to us by the Principal Research Officer in the Botswana Ministry of Local Government. However, one month later, just as we were about to leave Botswana with the elders, we were stopped by two investigators from the Directorate of Internal Security, who took away the elders’ passports and informed us that they considered the research permit invalid. Thirteen days later, following numerous calls and trips to the Office of the President, where we were strung along by Deputy

Permanent Secretary for Media and Government Communications Jeffress Ramsay, we left Botswana without the elders, having waited two weeks to receive a new research permit and new passports for them, or a letter of explanation as to why the project was being stopped.

What happened had nothing to do with the validity of a permit, and everything to do with the San elders. Of all the government officials we met during this period, only one thought that she had the decency to tell us that ‘no Bushman will ever cross the border’. The Botswana government treats the San people very poorly. They do not want this exposed, and most newspaper editors and journalists who have denounced the situation are banned from entry into the country.2 Our harrowing experience fell on deaf ears when we got home; we had expected to receive some support from the University of the Witwatersrand and the National Research Foundation, because they had funded a large part of the project, but more so because it was a human rights violation. However, their view was that this was an internal matter in which they could not intervene. The situation in Botswana is a sad one for San people, judging from the villages we visited around Ghanzi. The community is made up of many old and middle-aged people used to a traditional nomadic way of life. They have been relocated to small remote villages, where people from different language groups live together, on meagre government handouts because nothing but scrub bush grows in the area and men are prohibited from hunting and from collecting broken ostrich eggshells to make curios. Any interaction by visitors to the region with a local requires police clearance upon arrival at a village, and it is best to toe the line or informants will make sure that you do.

As a result of this encounter with the Botswana authorities, we realised that we would need to approach a San community living outside the country to find elders with whom we could work. In August 2012 we contacted the National Museum of Namibia in Windhoek and asked for advice as to which San communities might be interested in participating in our project, and how to obtain permission to work with them. Dr Eugene Marais of the Natural History Department at the museum directed us to the Nyae Nyae Conservancy in Tsumkwe, north-eastern Namibia, where some 2 300 Ju/’hoansi-speaking people still live a mostly traditional lifestyle (see Map 1 at the beginning of this book).3 Ju/’hoansi (pronounced jewtwasi) is a !Kung (also known as !Xun) dialect and also the name by which the people are known; the Ju/’hoansi were referred to as !Kung people in the publications of the 1950s to 1970s.4 Map 2 at the beginning of this book shows the distribution of the various San language groups in southern Africa.5 The communal Nyae Nyae Conservancy was established by the Namibian government in 1998 and covers 8 992 square kilometres of open savannah. Ju/’hoansi of the area maintain traditional hunting and gathering practices, but their hunting activities are limited by government quotas; as a result, hunters forfeit hunting in favour of cash, which is paid by trophy hunters to the Community Trust, a body elected by the Conservancy inhabitants to manage their local affairs.6 Traditional plant-gathering is limited by the demarcation of the nature reserve, which denies the Ju/’hoansi access to mongongo nut tree groves and tsin bean patches, plants that form part of their traditional diet.7 Some people have livestock, and some benefit from the sale of crafts to tourists and cooperatives.

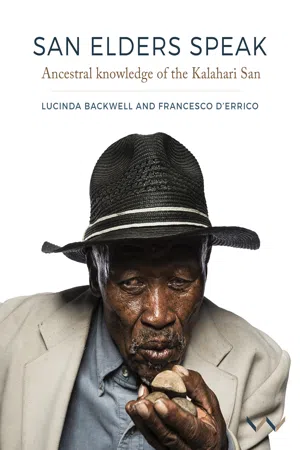

Four months later we travelled to Tsumkwe in the Nyae Nyae Conservancy, to meet the elders in the community and a translator whom we hoped would participate in the project, and to sign an agreement with the conservancy representatives to receive their cooperation in our study of the Fourie Collection. Tsamkxao ≠Oma (pronounced Toma), known as Chief Bobo (figure 1.1), who was 71 years of age at the time that we met him, agreed to enter into a memorandum of understanding with us, motivated by the desire to pass on his knowledge to future generations of San. He is a traditional hunter from /Aotcha and lives in Tsumkwe, where he is the Tsumkwe community leader; he is also the San representative at the United Nations. Dawid Cgunta Bo (figure 1.2) was 84 years of age when we met him. He called himself Cgunta (pronounced Gunta with a guttural g). He was a traditional healer and hunter who came from Dou Pos village. He died in 2020. Lena Gwaxan Cgunta (figure 1.3), a traditional gatherer from Dou Pos, was 56 years of age. She calls herself Gwaxan (pronounced Gwatla with a guttural g), and is the daughter of Dawid Cgunta Bo, who requested that she accompany him. Joa Cwi (figure 1.4), a traditional gatherer from Den/ui village, was 76 years of age; she died in 2018. ≠Oma Tsamkgao, known as Leon (figure 1.5), was 43 years of age when we met; he lives in Tsumkwe and works as a guide at the Tsumkwe Country Lodge. He is the son of Tsamkxao ≠Oma (Chief Bobo) and was our translator. He had helped John Marshall to complete his last documentary, A Kalahari Family, in 2003.8 We were relieved and delighted that Namibian passports were issued to all four elders and the translator within one day.

Figure 1.1 Tsamkxao ≠Oma from /Aotcha, Nyae Nyae, Namibia. Photograph by Brent Stirton.

Figure 1.2 Dawid Cgunta Bo from Dou Pos, Nyae Nyae, Namibia. Photograph by Francesco d’Errico.

Figure 1.3 Lena Gwaxan Cgunta from Dou Pos, Nyae Nyae, Namibia. Photograph by Francesco d’Errico.

Figure 1.4 Joa Cwi from Den/ui, Nyae Nyae, Namibia. Photograph by Francesco d’Errico.

Figure 1.5 ≠Oma Tsamkgao, known as Leon, from Tsumkwe, Namibia. Photograph by Francesco d’Errico.

On 15 April 2013 we left Johannesburg for Namibia, to spend five days in and around Tsumkwe and sign a legal agreement with the elders, represented by the Nyae Nyae Conservancy Committee members. Gwaxan’s husband //ao ≠Oma (figure 1.6), a traditional hunter, demonstrated for us how poison and glues are made. He also assisted us with an experiment designed to measure the effects of impact on a bone point shot with a traditional bow. This would prove useful later, when we analysed the construction and uses of items in the Fourie Collection that involved these techniques. While we were in the Tsumkwe area we also looked at and collected pieces of ostrich eggshell (leftovers from the production of beads) and small stones, which are used as the contents of leg rattles worn for dancing. On 20 April 2013 we all left Tsumkwe for the Namibian capital, Windhoek, from where we would fly to Johannesburg.

Figure 1.6 //ao ≠Oma from Dou Pos, Nyae Nyae, Namibia. Photograph by Francesco d’Errico.

From 22 to 30 April 2013 we worked through selected items in the Fourie Collection at Museum Africa (figure 1.7), asking the elders to examine and comment on each one. Generally, we discussed one object at a time, but in some cases we presented two or more objects of the same category to the elders together, and asked about their differences. We consulted a list of questions that we had prepared to ask about each object:

What was the Ju/’hoansi name of the object, and what was its function?

Did the elders know the object? Was it used by their group?

Who owns the object, who makes it, who uses it and who carries it?

When would an object be made, and when and where would it be used?

What is the raw material used to make the object, and what steps are followed in manufacturing it?

How is it used? Is it sharpened again after first use if necessary?

If an object was decorated, did the decoration have a meaning?

Was the object being discussed ever given as a gift or exchanged, and could the elders tell us any stories about it?

Figure 1.7 Three elders (Tsamkxao ≠Oma, Dawid Cgunta Bo and Lena Gwaxan Cgunta), our scribe, Kathleen Dollman, Brent Stirton, the photographer, and Lucinda Backwell, sitting in front of Museum Africa on Tuesday 23 April 2013. Photograph by Francesco d’Errico.

Our questions were conceived from the perspective of archaeologists interested in traditional technical systems, their possible links with past cultural adaptations, and the role that material culture plays in shaping and transmitting symbolic systems and social relationships. We already had some familiarity with the Fourie Collection; a year before the start of the project we had been through the collection with Diana Wall, the curator, and examined the catalogue of items with her. Unlike Fourie, who was particularly interested in hunting equipment, considered at the time as the main subsistence activity carried out by the San, we wished to elicit information on activities undertaken by all genders and age classes of San people, and on domestic as well as more spiritual aspects of their lives. We ...