eBook - ePub

Clinical Biochemistry and Metabolic Medicine

Martin Crook

This is a test

Compartir libro

- 416 páginas

- English

- ePUB (apto para móviles)

- Disponible en iOS y Android

eBook - ePub

Clinical Biochemistry and Metabolic Medicine

Martin Crook

Detalles del libro

Vista previa del libro

Índice

Citas

Información del libro

Whether you are following a problem-based, an integrated, or a more traditional medical course, clinical biochemistry is often viewed as one of the more challenging subjects to grasp. What you need is a single resource that not only explains the biochemical underpinnings of metabolic medicine, but also integrates laboratory findings with clinical p

Preguntas frecuentes

¿Cómo cancelo mi suscripción?

¿Cómo descargo los libros?

Por el momento, todos nuestros libros ePub adaptables a dispositivos móviles se pueden descargar a través de la aplicación. La mayor parte de nuestros PDF también se puede descargar y ya estamos trabajando para que el resto también sea descargable. Obtén más información aquí.

¿En qué se diferencian los planes de precios?

Ambos planes te permiten acceder por completo a la biblioteca y a todas las funciones de Perlego. Las únicas diferencias son el precio y el período de suscripción: con el plan anual ahorrarás en torno a un 30 % en comparación con 12 meses de un plan mensual.

¿Qué es Perlego?

Somos un servicio de suscripción de libros de texto en línea que te permite acceder a toda una biblioteca en línea por menos de lo que cuesta un libro al mes. Con más de un millón de libros sobre más de 1000 categorías, ¡tenemos todo lo que necesitas! Obtén más información aquí.

¿Perlego ofrece la función de texto a voz?

Busca el símbolo de lectura en voz alta en tu próximo libro para ver si puedes escucharlo. La herramienta de lectura en voz alta lee el texto en voz alta por ti, resaltando el texto a medida que se lee. Puedes pausarla, acelerarla y ralentizarla. Obtén más información aquí.

¿Es Clinical Biochemistry and Metabolic Medicine un PDF/ePUB en línea?

Sí, puedes acceder a Clinical Biochemistry and Metabolic Medicine de Martin Crook en formato PDF o ePUB, así como a otros libros populares de Medicina y Teoría, práctica y referencia médicas. Tenemos más de un millón de libros disponibles en nuestro catálogo para que explores.

Información

1 | Requesting laboratory tests and interpreting the results |

Requesting laboratory tests |

How often should I investigate the patient? |

When is a laboratory investigation ‘urgent’? |

Interpreting results |

Is the abnormality of diagnostic value? |

Diagnostic performance |

REQUESTING LABORATORY TESTS

There are many laboratory tests available to the clinician. Correctly used, these may provide useful information, but, if used inappropriately, they are at best useless and at worst misleading and dangerous.

In general, laboratory investigations are used:

• to help diagnosis or, when indicated, to screen for metabolic disease,

• to monitor treatment or detect complications,

• occasionally for medicolegal reasons or, with due permission from the patient, for research.

Overinvestigation of the patient may be harmful, causing unnecessary discomfort or inconvenience, delaying treatment or using resources that might be more usefully spent on other aspects of patient care. Before requesting an investigation, clinicians should consider whether its result would influence their clinical management of the patient.

Close liaison with laboratory staff is essential; they may be able to help determine the best and quickest procedure for investigation, interpret results and discover reasons for anomalous findings.

HOW OFTEN SHOULD I INVESTIGATE THE PATIENT?

This depends on the following:

• How quickly numerically significant changes are likely to occur: for example, concentrations of the main plasma protein fractions are unlikely to change significantly in less than a week (see Chapter 19), similarly for plasma thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH; see Chapter 11). See also Chapter 3.

• Whether a change, even if numerically significant, will alter treatment: for example, plasma transaminase activities may alter within 24 h in the course of acute hepatitis, but, once the diagnosis has been made, this is unlikely to affect treatment (see Chapter 17). By contrast, plasma potassium concentrations may alter rapidly in patients given large doses of diuretics and these alterations may indicate the need to instigate or change treatment (see Chapter 5).

Laboratory investigations are very rarely needed more than once daily, except in some patients receiving intensive therapy. If they are, only those that are essential should be repeated.

WHEN IS A LABORATORY INVESTIGATION ‘URGENT’?

The main reason for asking for an investigation to be performed ‘urgently’ is that an early answer will alter the patient’s clinical management. This is rarely the case and laboratory staff should be consulted and the sample ‘flagged’ as clearly urgent if the test is required immediately. Laboratories often use large analysers capable of assaying hundreds of samples per day (Fig. 1.1). Point-of-care testing can shorten result turnaround time and is discussed in Chapter 30.

Figure 1.1 A laboratory analyser used to assay hundreds of blood samples in a day. Reproduced with kind permission of Radiometer Limited.

Laboratories usually have ‘panic limits’, when highly abnormal test results indicate a potentially life-threatening condition that necessitates contacting the relevant medical staff immediately. To do so, laboratory staff must have accurate information about the location of the patient and the person to notify.

INTERPRETING RESULTS

When interpreting laboratory results, the clinician should ask the following questions:

• Is the result the correct one for the patient?

• Does the result fit with the clinical findings?

Remember to treat the patient and not the ‘laboratory numbers’.

• If it is the first time the test has been performed on this patient, is the result normal when the appropriate reference range is taken into account?

• If the result is abnormal, is the abnormality of diagnostic significance or is it a non-specific finding?

• If it is one of a series of results, has there been a change and, if so, is this change clinically significant?

Abnormal results, particularly if unexpected and indicating the need for clinical intervention, are best repeated.

CASE 1

A blood sample from a 4-year-old boy with abdominal pain was sent to the laboratory from an accident and emergency department. Some of the results were as follows:

Plasma

Bilirubin 14 μmol/L (< 20)

Alanine transaminase 14 U/L (< 42)

Alkaline phosphatase 326 U/L (< 250)

Albumin 40 g/L (35–45)

γ-Glutamyl transferase 14 U/L (< 55)

Albumin-adjusted calcium 2.34 mmol/L (2.15–2.55)

DISCUSSION

The patient’s age was not given on the request form and the laboratory computer system ‘automatically’ used the reference ranges for adults. The plasma alkaline phosphatase activity is raised if compared with the adult reference range, but in fact is within ‘normal limits’ for a child of 4 years (60–425). See also Chapters 6 and 18.

Test reference ranges

By convention, a reference (‘normal’) range (or interval) usually includes 95 per cent of the test results obtained from a healthy and sometimes age- and sex-defined population. For the majority of tests, the individual’s results for any constituent are distributed around this mean in a ‘normal’ (Gaussian) distribution, the 95 per cent limits being about two standard deviations from the mean. For other tests, the reference distribution may be skewed, either to the right or to the left, around the population median. Remember that 2.5 per cent of the results at either end will be outside the reference range; such results are not necessarily abnormal for that individual. All that can be said with certainty is that the probability that a result is abnormal increases the further it is from the mean or median until, eventually, this probability approaches 100 per cent. Furthermore, a normal result does not necessarily exclude the disease that is being sought; a test result within the population reference range may be abnormal for that individual.

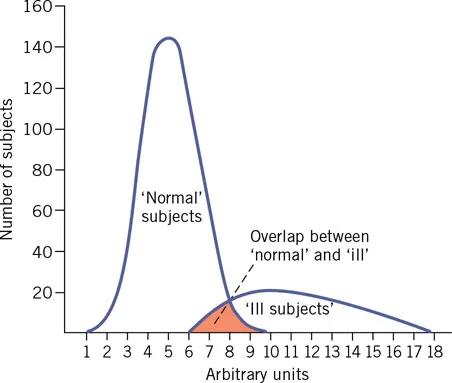

Very few biochemical tests clearly separate a ‘normal’ population from an ‘abnormal’ population. For most there is a range of values in which ‘normal’ and ‘abnormal’ overlap (Fig. 1.2), the extent of the overlap differing for individual tests. There is a 5 per cent chance that one result will fall outside the reference range, and with 20 tests a 64 per cent chance, i.e. the more tests done, the more likely it is that one will be statistically abnormal.

No result of any investigation should be interpreted without consulting the reference range issued by the laboratory carrying out the assay. Some analytes have risk limits for treatment, such as plasma glucose (see Chapter 12), or target or therapeutic limits, such as plasma cholesterol (see Chapter 13).

Figure 1.2 Theoretical distribution of values for ‘normal’ and ‘abnormal’ subjects, showing overlap at the upper end of the reference range.

Various non-pathological factors may affect the results of investigations, the following being some of the more important ones.

Between-individual differences

Physiological factors such as the following affect the interpretation of results.

Age-related differences

These include, for example, bilirubin in the neonate (see Chapter 26) and plasma alkaline phosphatase activity, which is higher in children and the elderly (see Chapter 18).

Sex-related differences

Examples of sex-related differences include plasma urate, which is higher in males, and high-density lipopr...