![]()

1

Unraveling

The routes leading west from Petersburg and Richmond were a gruesome sight in early April 1865. The final week of March had brought torrents of rain to Southside Virginia, swelling creeks and streams and leaving roads clogged with ankle-deep mud. Rival armies likewise flooded the countryside. Anyone witnessing the scene might have easily discerned which would be victorious. As Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia tramped west, desperately hoping to find passage south to its Confederate allies commanded by Joseph E. Johnston, Ulysses S. Grant’s Union forces pursued their quarry, growing in belief that four years of war could be brought at last to an end.

Lee’s army appeared to be dissolving into the landscape. Soldiers had abandoned their mud-choked muskets. Cap boxes and cartridges lay strewn in a mad confusion. Discarded clothing, cooking utensils, personal baggage, blankets, and papers soaked with rain littered the way, while the dead and wounded filled the woods. Burning and broken-down wagons, ambulances, and caissons mired in the thick sludge became obstacles to avoid, as did the dead and dying horses and mules that had hauled them.1

Near the rear of Lee’s thinning ranks marched James “Eddie” Whitehorne of the 12th Virginia. Now twenty-five years old, Whitehorne had grown up on his family farm in Greensville County, near the North Carolina border. In June 1861, he enlisted as a private in Company F, the Huger Greys, and by August he had won promotion to corporal and then first sergeant. But there his rise through the ranks ended, as would much of his time in the field. During the war’s second year, terrible rheumatism forced him to take extended periods of leave. Rejoining his regiment in the spring of 1863, he fought at Chancellorsville and Gettysburg, only to have a shell fragment smash both his legs on the second day of fighting. Incapacitated until June 1864, he rejoined his comrades, but only weeks after returning to the field, he was hit again in the leg at the battle of the Crater. Following two more months of medical furlough, he finally returned to the 12th Virginia in October. Now he found himself in a column fleeing west after abandoning the Confederate fortifications between Richmond and Petersburg in the early morning hours of April 3. In an all-night march he had covered more than twenty-three miles before crossing the Appomattox River by pontoon boat near Goode’s Bridge. Exhausted and in terrible leg pain, Whitehorne confided in his diary, “I have a growing fear I shall not be able to keep up tomorrow.”2 But on he pressed.

Many of his comrades had decided differently. Desertions had been a problem in the army throughout the winter. From the camp of the 8th Virginia, E. Augustus Klipstein informed his wife in early February that four deserters from Stewart’s Brigade had been executed. “They had better have remained faithful to the cause of their country, but there are a great many croakers and a good deal of dissatisfaction in the army,” he wrote. But he understood why: “The prospect of another bloody campaign and short rations are doing its work.”3 Union forces enticed their foes to leave the siege lines as well, including offers of free transportation to the North and government employment. Other surrendering rebels received twenty-six dollars for turning over their guns and equipment to the U.S. forces. “I think that is pretty good inducements,” wrote one Union soldier in early March. “They say they will desert by Brigades when there is a move.”4

With the approach of the spring campaign season, the situation had become so untenable that on March 27 Lee issued what would prove his last order before the surrender, threatening to execute any man who so much as joked about deserting. “Those indulging such jests will find it difficult on a trial to rebut the presumption of guilt arising from their words,” Lee warned, commanding that his order be read to each company once a day for three days and to every regiment at dress parade once a week for a month.5

But the desertions continued as the army abandoned Richmond and Petersburg. On the afternoon of April 3 near Namozine Church, General Sheridan reported that his cavalry had captured nearly 1,200 rebels, informing Grant that the surrounding woods were “filled with deserters and stragglers.”6 An officer with the 7th United States Colored Troops (USCT) observed that the proximity to home seemed to induce Virginia Confederates to give up the fight sooner than their comrades from farther south. “They say that the whole Rebel forces that belong in Virginia will desert Lee as soon as he leaves for North Carolina,” the officer wrote to his wife.7

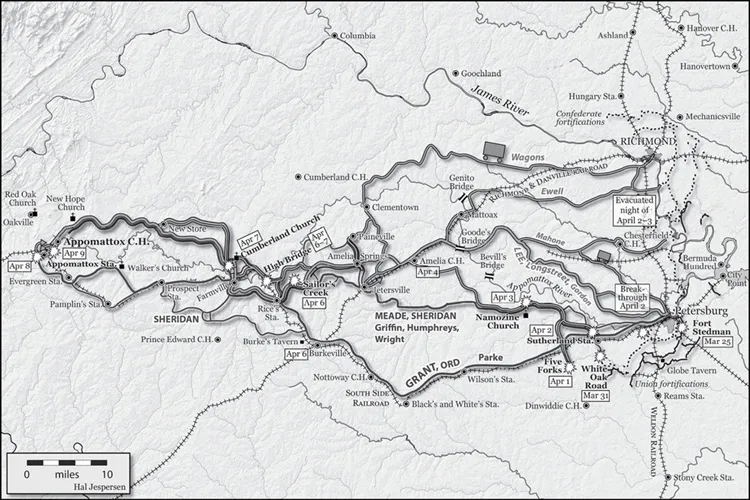

Appomattox campaign, April 2–9, 1865.

Benjamin Sims of the 17th Virginia was one such deserter. Even before the retreat began, the conscript from Louisa County fled along with much of his regiment at Five Forks on April 1. “We take to the woods, every man for himself,” he scribbled in his journal, adding that he had joined up with two of his company about a mile from the field. Unable to find a spot to cross the Appomattox River on April 2, he and a comrade decided to go home. But even those from farther afield elected to abandon their units.8 The number of stragglers captured by pursuing Union forces daily ran in the thousands, and stories came from all directions of Confederates taking to the woods and heading home, some in small groups, others in large squads.

Each day, Union confidence surged. For nearly three years, Union troops had struggled to defeat Lee’s seemingly unbeatable army. Now Federal cavalry reported that the rebels had been forced to destroy countless wagons, caissons, and munitions as they fled. Propelled forward, Union troops marched twenty to thirty miles a day in the mire, striving to ignore hunger and exhaustion. “My feet are full of blisters, and I am played out,” wrote one weary soldier to his father. But weariness did not mean they would quit. As one Union artillerist declared, they could taste the opportunity to finally “bag Lee.”9

After another all-night march through more heavy rain, on April 6 Lee’s army advanced southwest until a fight erupted along the banks of Sailor’s Creek. From Brig. Gen. Reuben Lindsay Walker’s artillery train, James Albright witnessed the scene along a rise just across the creek. “I have never seen such confusion,” he confessed that evening, “nor anything so nearly approaching a rout.” When the quartermaster, commissary, and hospital wagons tried to cross a small gorge along the creek, they piled upon each other, and men struggled to pull weak horses and mules up out of the soggy creek bottom. Soon there was no choice but for the Confederates to abandon yet more precious ordnance, ammunition, and other stores.10

Albright could not have fathomed such a scene four years earlier. Born in Greensboro, North Carolina, in 1835, he had apprenticed himself at the age of sixteen to the printer of the Greensboro Times, a weekly literary paper. Quickly learning both the mechanics of printing and writing, by 1857 Albright could claim a byline as a coeditor along with his childhood friend C. C. Cole. Throughout the secession winter of 1860–61, Cole and Albright continued to publish their paper, voicing their support of the Union and opposition to secession. But in the aftermath of Fort Sumter and Lincoln’s call for 75,000 troops, they threw the full measure of their support behind the Confederacy. “We were born and reared in this town,” they wrote in an editorial that spring, and “therefore, North Carolina shall be first in our heart and the Confederate states, second—and for these we will battle, no matter who assaults them.” Demonstrating his loyalty to his state and new country, Cole enlisted in the spring of 1861 along with other members of the Guilford Grays. But unlike most of the young men who marched off to war, Albright had a young wife and three-year-old son. He would stay in Greensboro as the sole editor and owner of the weekly paper.11

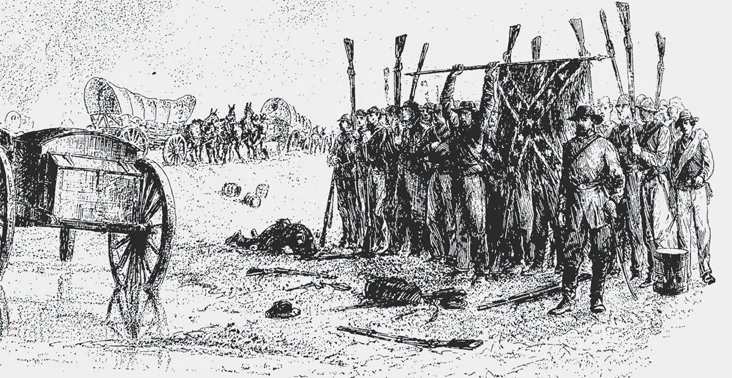

The Last of Ewell’s Corps, April 6, 1865, based on a sketch by Alfred R. Waud. In Battles and Leaders of the Civil War, ed. Robert Underwood Johnson and Clarence Clough Buel, vol. 4 (New York: Century, 1887), 721.

For the next year, Albright fought the war through words. Each week the Times reported from the Virginia battlefields, reprinted messages from President Jefferson Davis, and called on the town’s women to help gather provisions for their soldiers. In the spring of 1862, with Confederate conscription looming, the newly widowed Albright recognized he could no longer remain at home. Closing down his printshop and securing someone to take care of his young son, in late April he joined the 13th Battalion North Carolina Artillery (soon transferred to the 12th Battalion Virginia Artillery), where Albright found himself detailed as an ordnance sergeant for the entire battalion.12

Three years later, the thirty-year-old looked around him to see the Army of Northern Virginia crumbling. As night began to fall along the banks of Little Sailor’s Creek, Albright and the rest of the army managed to slip away, but the battle had proven especially costly at a moment when Lee could little afford to lose any more men. His army had sustained approximately 7,700 casualties (compared with only 1,148 among Union forces), in addition to nearly 300 wagons and ambulances. Eight generals had been captured, including Lt. Gen. Richard S. Ewell and Maj. Gen. George Washington Custis Lee, the commanding general’s oldest son. Witnessing the disorganized mob from high ground overlooking the creek late that day, Lee quietly exclaimed, “My God! has the army been dissolved?”13

The losses from those taken prisoner or killed and wounded proved catastrophic enough. But another 1,450 Confederates escaped the field, failing to rejoin their commands. Among them was Maj. Joseph G. Blount of the Macon Light Artillery. Deployed on a ridge above Sailor’s Creek, his gunners had attempted to help Maj. Gen. John B. Gordon’s Second Corps hold off the Federals. When it became clear that this would be impossible, Blount and his battery left with their two remaining guns and headed west toward Lynchburg.14 So too did countless others, including Richard Chapman and William H. Reed of the 32nd Virginia. The departures, Albright observed that evening in his diary, would soon ruin Lee’s army.15

Even with the attrition, the Union high command recognized the tenacity with which Confederates continued to fight. Sheridan insisted that Sailor’s Creek proved “one of the severest conflicts of the war, for the enemy fought with desperation to escape capture, and we, bent on his destruction, were no less eager and determined.” Faced with annihilation and starvation on one hand or surrender on the other, one Union soldier observed that the Confederates continued to “cling to General Lee with childlike faith” as they pressed on west toward Farmville and looked for their opportunity to turn south toward General Johnston.16 But still the Confederate ranks thinned. After another night march, the third in five days, thousands of stragglers dropped out of the column, some simply collapsing along roadbeds, others wandering listlessly through Virginia’s dripping woods. Trailing behind Lee’s men, the lead division of the Union Second Corps picked up individuals and entire squads, many literally sleeping on the side of the road.17 Hustled to their feet, the men reversed their march back toward Richmond. Now that Union prisoners had been liberated from Libby Prison, the bluecoats happily refilled it with Lee’s men, one soldier estimating that upward of 3,000 rebels now occupied the wretched site.18

By the time Grant arrived in Farmville on the afternoon of April 7, he recognized that Lee could not hold out much longer. Desertions alone suggested that his army was disintegrating. But the capture of thousands of prisoners at Sailor’s Creek and elsewhere accompanied by the destruction of so many wagons convinced Grant that the time was right to end the fighting. At 5:00 P.M., sitting on the brick front porch of the Randolph House (later called the Prince Edward Hotel), he issued a note inviting Lee to surrender. “The results of last week must convince you of the hopelessness of further resistance,” Grant began. “I feel that it is so, and regard it as my duty to shift from myself the responsibility of any further effusion of blood by asking of you the surrender of that portion of the Confederate army known as the Army of Northern Virginia.”19

Just after nightfall, the flag of truce appeared in front of Confederate lines bearing Grant’s letter. At the Blanton House in Cumberland County, Lee took the note, read it silently, and then, without uttering a word, passed it to Lt. Gen. James Longstreet. “Not yet,” Longstreet replied. Lee trusted the general he called his “Old War Horse” perhaps more than any other senior officer. He assured Lee that it was not yet time to capitulate. With such encouragement, Lee responded to Grant that he was not ready to surrender; even so, he wondered what the terms of surrender might entail. Until he heard from Grant, however, he would continue to press his army west.20

Another night march made Eddie Whitehorne’s leg throb with pain, yet on he marched even as others seemed to melt into the countryside. William Gordon McCabe, a twenty-three-year-old staff officer with the 1st Company of the Richmond Howitzers, ascribed the attrition to cowardice rather than fatigue. “This is one of the very saddest days of my life,” he wrote on April 7. “When I see the crowd of stragglers and then look across at the Blue Ridge and think that I must give up this beloved Virginia because of the faintheartedness and cowardice of these men, who have deserted their colors, my heart bursts with a sob. I am willing and ready, if God spares my life, to follow the old battle flag to the gulf of Mexico. If our men desert it, and I am not killed, I shall be forever an exile,” he vowed. “If we lose our country,” he surmised, “it is our own fault.” He would do his best, however, to prevent such an outcome, arresting scores of laggards along the route.21 Other officers resorted to more desperate measures to keep men in the ranks, including threats to shoot those who appeared eager to depart. Some soldiers could not be compelled to continue even under threat. But most marched on, determined to press the fight.22

Just south of Appomattox Court House, an exhausted and famished James Albright had settled down into camp near the station along the South Side Railroad.23 Traveling with Walker’s reserve artillery train, Albright and others now led the Confederate column, crossing the headwaters of the Appomattox before passing through Appomattox Court House, a village that consisted of a post office in the general store, a handful of homes, and its central feature—the courthouse. Reaching a rise about a half mile above the railroad station around 3:00 P.M. on April 8, the artillerists unharnessed their few remaining horses ...