![]()

CHAPTER ONE

Insure, Britannia! Marine Insurance and the Maritime Empire, 1622–1776

Being asked, Whether there was any imaginable risk in trade, stated intelligibly by a merchant of character, that could not meet with insurance in London? he answered, That he did not imagine there was, every risk having its price.

—Examination of William Bell, London insurance broker, by a Select Committee of the House of Commons, Great Britain, 1778

North America’s first insurance brokerages opened in the mid-eighteenth century. They helped colonial merchants take advantage of the immense new commercial opportunities that emerged alongside the hazards of near-constant imperial warfare. Around the British Empire, growing populations of colonists demanded ever-greater quantities of textiles, metalware, other manufactured goods, and enslaved laborers. They produced more goods for overseas markets, such as sugar, rice, iron, tobacco, and wheat, and in New England, they built large numbers of new ships to transport these goods. This commercial expansion was intertwined with the development of the British state, which taxed more and borrowed more, employing new technologies of finance and engaging merchant capital in order to engage in ever-greater wars in Europe and around the world. Although the wars disrupted commerce, they were also opportunities in themselves, for they reshaped trading patterns and gave rise to vast new demands. They were fought by soldiers and mariners who required large quantities of supplies, and they sometimes resulted in imperial expansion, which provided still more opportunities for trade.1

In retrospect, it is easy to view this as an age of inexorable growth, but—from a colonial vantage point, particularly—the commercial outlook of the eighteenth century was none too certain. Though the colonial economy grew in the long term, markets lurched from shortages to gluts in the short term, and territories were unpredictably won and lost, or opened and closed to traders. Moreover, to colonial merchants’ frustration, the empire’s overarching commitment to countering its rivals did not translate into specific and reliable plans for long-term defense of its own colonies’ shipping. In such a world, the value of marine insurance was obvious. By the early 1770s, about fifteen or twenty brokers sold insurance in the North American colonies. In addition, scores of colonial American merchants likely acquired insurance or related services from their neighbors without resorting to a broker. By imperial standards, the scale of this American insurance sector was extremely modest. Most American towns had only one broker or none at all, and most underwriters were simply local merchants seeking to diversify their risks by insuring one another. Nevertheless, the appearance of local brokerages demonstrated that significant economic development had taken place in the Anglo-American colonies. By helping local merchants pool their risks, brokers drove that development still further.2

It is easy to see the ways in which eighteenth-century American marine insurers, like their British counterparts, lived in symbiosis with the empire. American brokerages owed their prosperity to Britain’s flourishing merchant marine and expanding fiscal-military state. The British navy protected them from losses. The brokerages exhorted their customers to obey British laws, and they submitted their disputes—at least sometimes—to British courts. “Rule, Britannia!” sang London stage actors and Bristol sailors of the eighteenth century, boasting of the British navy’s might. “Insure, Britannia!” sang the new brokerage offices in quieter, but equally pious, voices. Like the navy, the brokers and underwriters safeguarded the empire.3

Yet the relationship between marine insurance and the British Empire was not as harmonious as it appeared. In fact, there were ways in which the insurance business existed in fundamental tension with the empire.4 British underwriters happily insured the vessels and cargoes of Britain’s rivals and enemies, and even as the British insurance sector publicly commanded its customers to obey British law, it profited from the many quasi-legal and outright illegal ventures undertaken by the merchants it insured. The British Empire’s growth produced new commercial hazards that merchants and insurers complained about, such as the foreign privateers set in motion by imperial wars or the increasingly intrusive British jurisdictional systems that eventually—and fatefully—chafed American colonial leadership. Even the empire’s weaknesses yielded profits to underwriters, because British merchants would pay most for insurance when they could not count on the navy’s protection.

The tensions between marine insurance and the British Empire ran deeper yet, because insurance was always something more than a business. It was also, by necessity, a mechanism through which insurers regulated the behavior of the merchants who bought insurance policies. Since most underwriters were merchants themselves, marine insurance became, in effect, a system for merchant self-governance. Its innumerable rules were stitched together unevenly out of early modern legal rulings, written and unwritten merchant traditions, and formal agreements among small groups of practitioners. Its promulgators and enforcers ranged from experienced brokers and wealthy underwriters to lawyers in imperial capitals, shipmasters at sea, notaries public, local courts, and revered judges. Marine insurance predated the early modern state, and even as the state consolidated its authority, insurance stubbornly retained its transnational character.5

Ultimately, however, it took merchant mythology to transmute insurance rules into something we can understand, in some register, as law. The core myths of eighteenth-century marine insurance included the notions that merchants had always governed one another according to the dictates of lex mercatoria, the eternal laws of merchants; that these laws existed outside of the state; and that only expert practitioners could properly interpret them. Though historically inaccurate, these myths proved extremely useful for insurance brokers and underwriters. They enabled insurers to continually reimagine their business as something beyond the reach of the state, no matter how mighty that state was becoming, and no matter how directly insurers interposed themselves in the making of states’ laws.

The modest marine insurance brokerages that opened in British North America during the eighteenth century belonged to the British Empire, but they also belonged to this older transnational system held together by traditional merchant practice and mythology. American merchants trusted the new brokerages not only because their colonial neighbors ran them—or because their neighbors behaved as British insurers did—but also because they believed that all insurance everywhere fundamentally worked the same way and that all merchants were bound to follow its rules.

As American insurance brokerages became significant nodes of capital, expertise, commercial news, and political intelligence within the British Empire, they reinforced Americans’ commercial ties to the empire. At the same time, these new brokerages were deepening American merchants’ connections to the old transnational system of marine insurance that operated independent of the empire and even in tension with it. When the American Revolutionary War arrived, it became evident that insurance brokerages were well suited to support the autonomous activities of local communities of merchants. Many American brokerages would lend their strength to the cause. But in the end, they would never entirely belong to the republic that the Revolution created.

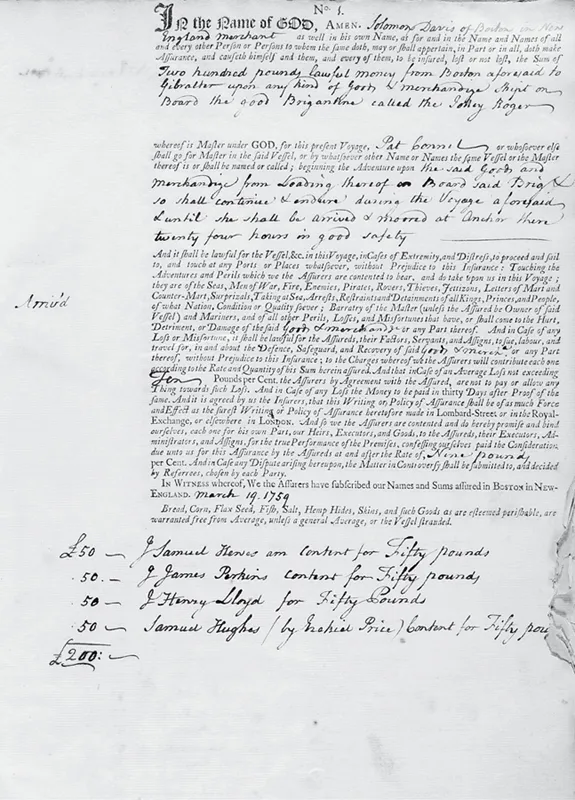

RULES

To understand the ways in which insurance constituted a system of governance, we must begin with the rules by which the business generally operated. At first glance, insurance’s rules appear simple and straightforward. The standard eighteenth-century British insurance contract was short enough to be printed on a single quarto sheet with plenty of room to spare. It explained the risks against which a merchant was customarily insured, declared when the insured risk began and ended, and outlined the procedures that would take place in the case of loss (Figure 5).

All was not as it appeared, however. Beneath the surface of this single sheet of paper lay a bottomless ocean of rules, customs, provisos, and exceptions that did not emanate from any single authority or feature any unified mechanism for enforcement. By the mid-eighteenth century, every word in the standard insurance contract had been elaborated on, interpreted, opined upon, and litigated in multiple venues. But this chaos was bound together with a simple conceptual cord. If you were to ask any one of the men coming and going from Lloyd’s of London or a colonial insurance office how it all worked, they would answer in a single voice: insurance was a business conducted according to lex mercatoria.

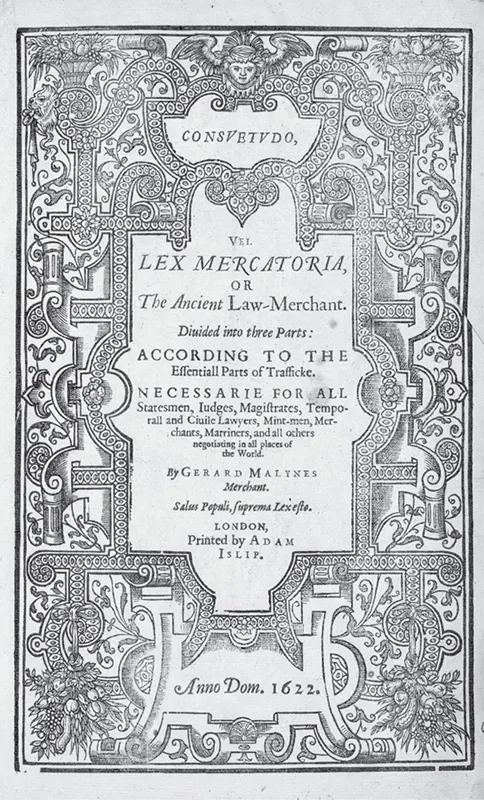

Although no single living expert could be said to possess the authoritative understanding of these “laws of merchants” or of how they defined the insurance business, there did exist, at least, an obvious starting point for those who wished to learn. During the seventeenth century and the first half of the eighteenth, the most important English-language source of lex mercatoria was a sprawling tome, more than five hundred pages in length, published in London in 1622 by the Antwerp-born merchant Gerard Malynes. A self-appointed Deuteronomist of merchant law, Malynes entitled his publication Consuetudo (“custom”), vel (“or”), Lex Mercatoria; or, The Ancient Law-Merchant (Figure 6).6

In this volume, Malynes organized the laws of merchants around a tripartite vision of commerce, composed of commodities (commerce’s “body”), money (its “soul”), and bills of exchange (its “spirit”). But his content immediately and hopelessly overflowed these categories. The “commodities” section did, as promised, address “the Commodities of all Countreys” and other concrete matters such as weights and measures. But it also offered “a geometricall description of the world” as well as discussions of letters of credit, banks, a history of the laws of the sea, and several hefty chapters on marine insurance. Later authors would do little better. In Giles Jacob’s Lex Mercatoria of 1718 (340 pages), Jacques Savary des Brûlons’s Dictionnaire universel de commerce of 1723–1730 (1,873 pages in the English translation), and Wyndham Beawes’s Lex Mercatoria of 1751 (920 pages), the laws of merchants continued to defy summary and organization. Yet the haphazard organization and blurry generic identity of lex mercatoria did not discourage a long line of later authors from concurring with his judgment that it was a single body of law, composed of whatever merchants generally knew, believed, and did, and that it was admissible into a variety of legal settings. Even nineteenth-century experts on lex mercatoria were apt to quote the seventeenth-century Neapolitan jurist Francesco Roccus, who had declared, “When the practice and observance of merchants are notorious, any good proof of them should be admitted.”7

Figure 5. First insurance policy issued by the brokerage office of Ezekiel Price, Mar. 19, 1759, Marine Insurance Policies, 1756–1781, I, MSS .L50 .2, Boston Athenaeum. The language used to describe hazards that the insured was protected against (“Seas, Men of War, Fire …”) bears a remarkable similarity to the language featured on policies issued in Pisa and Florence in the late fourteenth century (see Frederic Rockwell Sanborn and the American Historical Association, Origins of the Early English Maritime and Commercial Law [New York, 1930], 253). The text reads as follows:

No. [Policy Number]

IN the Name of GOD, AMEN. [Property owner’s name] as well as in his own Name, as for and in the Name and Names of all and every other Person or Persons to whom the same doth, may or shall appertain, in Part or in all, doth make Assurance, and causeth himself and them, and every of them, to be insured, lost or not lost, the Sum of [property insured]

whereof is Master under GOD, for this present Voyage, [shipmaster’s name] or whosoever else shall go for Master in the said Vessel, or by whatsoever other Name or Names the same Vessel or the Master thereof is or shall be named or called; beginning the Adventure upon [voyage]

And it shall be lawful for the Vessel, etc. in this Voyage, in Cases of Extremity, and Distress, to proceed and sail to, and touch at any Ports or Places whatsoever, without Prejudice to this Insurance: Touching the Adventures and Perils which we the Assurers are contented to bear, and do take upon us in this Voyage; they are of the Seas, Men of War, Fire, Enemies, Pirates, Rovers, Thieves, Jettizons, Letters of Mart and Counter-Mart, Surprizals, Taking at Sea, Arrests, Restraints and Detainments of all Kings, Princes, and People, of what Nation, Condition or Quality soever; Barratry of the Master (unless the Assured be Owner of said Vessel) and Mariners, and of all other Perils, Losses, and Misfortunes that have, or shall come to the Hurt, Detriment, or Damage of the said [goods / merchandise / vessel] or any Part thereof. And in Case of any Loss or Misfortune, it shall be lawful for the Assureds, their Factors, Servants, and Assigns, to sue, labour, and travel for, in and about the Defence, Safeguard, and Recovery of said [goods / merchandise / vessel] or any Part thereof, without Prejudice to this Insurance; to the Charges whereof we the Assurers will contribute each one according to the Rate and Quantity of his Sum herein assured. And that in Case of an Average Loss not exceeding [number] Pounds per Cent. the Assurers by Agreement with the Assured, are not to pay or allow any Thing towards such Loss. And in Case of any Loss the Money to be paid in thirty Days after Proof of the same. And it is agreed by us the Insurers, that this Writing or Policy of Assurance shall be of as much Force and Effect as the surest Writing or Policy of Assurance heretofore made in Lombard-Street or in the Royal-Exchange, or elsewhere in LONDON. And so we the Assurers are contented and do hereby promise and bind ourselves, each one for his own Part, our Heirs, Executors, and Goods, to the Assureds, their Executors, Administrators, and Assigns, for the true Performance of the Premises, confessing ourselves paid the Consideration due unto us for this Assurance by the Assureds at and after the Rate of, [number] per Cent. And in Case any Dispute arising hereupon, the Matter in Controversy shall be submitted to, and decided by Referrees, chosen by each Party.

IN WITNESS whereof, We the Assurers have subscribed our Names and Sums assured in BOSTON in NEW-ENGLAND. [date]

Bread, Corn, Flax Seed, Fish, Salt, Hemp Hides, Skins, and such Goods as are esteemed perishable, are warranted free from Average, unless a general Average, or the Vessel stranded.

Figure 6. Title page, Gerard Malynes, Consuetudo, vel, Lex Mercatoria; or, The Ancient Law-Merchant … (London, 1622). By insisting that he was the heir to an important legal tradition, Malynes played an important part in creating one. RB #346265. The Huntington Library, San Marino, Calif.

Compilations of merchant law published between the seventeenth and nineteenth centuries varied widely, but they usually provided comprehensive discussions of marine insurance. This highly technical, fundamentally transnational business, administered by experienced merchants of multiple nationalities, obviously belonged in lex mercatoria more than it belonged in any compilation of national laws. Insurance brokers and underwriters, for their part, were by necessity lex mercatoria’s preeminent experts, both because of what their business expected from them and what they expected from those they insured. Early modern marine insurance evolved out of more direct, premodern forms of risk sharing among captain and crew, and in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, the risk-taking insurer was still required to act, in some respects, as if he were aboard the vessel. It was his customary responsibility, lex mercatoria averred, to understand navigation, geography, and weather; to know the master of the ship and the ship’s “goodness,” and the distance to the vessel’s destination. The insurer was also obligated to understand proper bookkeeping and the correct ways of doing business in the various countries where his insureds were bound. If he failed in this respect, business losses were his own fault. He additionally had to ensure his insureds’ own observance of lex mercatoria. He had staked money on the voyage’s success, but since he did not travel with the vessel, he could not advise the captain or take control of the wheel. The only way he could exert his authority was by forcing his insureds to demonstrate, in the case of a loss, that they had adhered to the terms of the insurance contract. His insureds would also have to demonstrate, by producing appropriate paperwork, that they had followed the proper procedures dictated by lex mercatoria more generally. Insurers had to follow the rules, and they had to make sure that merchants and shipmasters followed them, as well.8

MYTH CREATE...