![]()

CHAPTER 1

1066 AND ALL THAT

I’ll tell of the Battle of Hastings,

As happened in days long gone by,

When Duke William became King of England,

And ‘Arold got shot in the eye.

Marriott Edgar

AFTERNOON ON 14 OCTOBER 1066, AUTUMN in the garden of England. The battle had lasted all day and it wasn’t over yet. The stubborn shield wall was holding despite constant battering from Norman infantry and cavalry. Less than a month before, the last great clash of the Viking Age had occurred far to the north at Stamford Bridge, east of York. Harald Hardrada and King Harold of England’s renegade brother Tostig faced the last English king and his elite huscarls. The Norse invaders were cut to pieces; Hardrada died a true Viking, sword in hand.

Now King Harold faced a different enemy: not just a new opponent but a different set of tactics. The cream of Duke William’s army was comprised of mounted knights, warriors on horseback. It was a new fashion but for hours the old shield wall had still pushed them back. Dusk wasn’t far off. Harold just had to hang on. A commando of knights has forced its way onto the plateau – most won’t be coming back but at least four get through and kill Harold. The last Saxon King may or may not have been shot in the eye, but he’s still dead and his body horribly mutilated. As his banner dipped and fell, so did Saxon England. It was a whole new era – the Age of Chivalry.

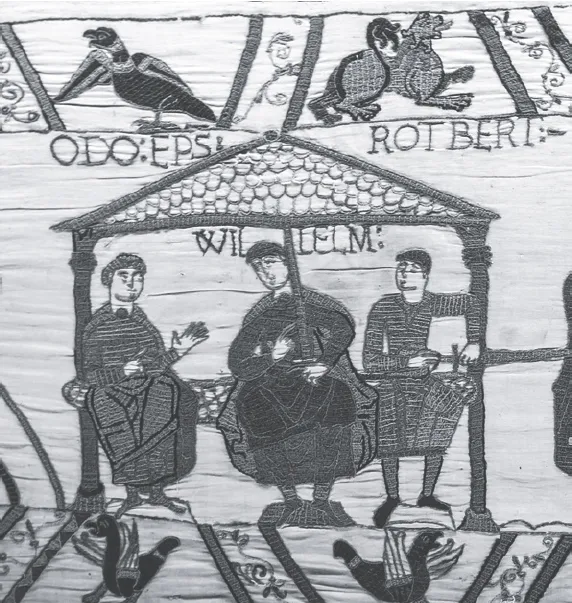

Detail from the Bayeux Tapestry showing William the Conqueror (centre), his half-brothers Robert, Count of Mortain (right) and Odo, Bishop of Bayeux in the Duchy of Normandy (left).

Origins of knighthood

What made a knight? Origins are lost in history but it may have been Charlemagne who, fearful of Danish raiders – ruffians, as he called them – appointed key local men to defend their communities. Now Charlemagne was a Christian and it was his rather heavy-handed conversion tactics that had irritated the pagan Danes. But at the outset there was no direct link between knighthood and the church. That came later. When Pope Urban called for a great crusade to free the Holy Land in 1095, he may have had it in mind to provide job opportunities for unemployed knights who were otherwise a menace at home. He made it official, taking the cross became a badge of respectability, and the initiate had to promise he would

defend to the uttermost the oppressed, the widow and the orphan, and that women of noble birth should enjoy his special care.

This really was the birth of chivalry – the notion that a knight was more than a bruiser, a professional fighter; he represented an ideal of service and honour.

This new connection between church and knight, between faith and the sword, meant that being a knight put you into a special category. The ideals of chivalry were what defined you, and knighthood was a status that had to be earned rather than one automatically conferred by birth. The poorest gentleman from the shires, any rustic D’Artagnan, was likely to be as good a knight as anyone from higher up the ladder. Becoming a knight involved a religious passage akin to secular ordination, and this was carried further by the knightly orders which grew from the crusades (see Chapter 2).

As we’ve seen from the glittering career of William Marshal, the tournament was both an industry and an obsession. One stage removed from gladiatorial combat, this was a hugely popular spectator sport: the bloodier, the better. Tournaments were the Rotary Clubs of their day, an international freemasonry of knights who by breeding, status and training were elevated way above the lumpen masses. But the highly stylised jousts of the Tudor age were a long way in the future, as at this time tournaments were rough and ready, a free-for-all where injuries and death were by no means rare.

In 1274 King Edward I was invited by the Count of Chalons to take part in a tournament he’d organised. Hundreds were involved on each side and the fracas became known as the Little Battle of Chalons. The count tried every trick he knew to throw Edward from his saddle, but the king was too quick for him and it was the count who ended up in the dust. Thoroughly humiliated, he re-mounted and attacked Edward full-on. His French followers joined in with gusto. As did the English archers who let fly and shot many of their hosts. Dozens died, and yet it wasn’t until the next century that rules were instated. The safety fence separating combatants – the tilt – wasn’t introduced till 1420.

The Homeric ideal of single combat translated easily from joust to battlefield. Robert the Bruce won a significant victory when, on 23 June 1314, the first day of Bannockburn, despite only being lightly armoured, he brained Sir Henry de Bohun, an English knight who came at him in full kit. Earlier, William Wallace (‘Braveheart’) and Bishop Bek had slogged it out in the streets of Glasgow. Before he fought the Count of Chalons, Edward had won the Second Barons’ War. In the Forest of Alton, in what may have been a confused skirmish, the rebel knight Adam Gurdon, a leading local rebel had clashed with Edward in single combat. Gurdon was a tough fighter with something of a reputation and the duel was long and hard-fought. Edward won but was prepared to show mercy to a worthy adversary and spared Gurdon.

Sixteenth-century German print, showing Henry II of France jousting.

An Englishman’s castle

The knightly warrior was defined by his status, by his membership of the feudal elite, distinguished by his armour, his weapons and his warhorse. Moreover, he was identified by his castle. Prior to 1066, these were rare in England. Thereafter, they proliferated. Not merely a fort or a refuge, the castle was the dominion of the feudal gentry writ in solid masonry.

Castles live in the mind, the visible traces of the age of knighthood. Castell Coch in South Wales and fantastical Neuschwanstein in Bavaria (a fairy-tale confection commissioned by King Ludwig II) were both built as 19th century homage to the ideal. Arundel, Alnwick, Bamburgh, Edinburgh, Framlingham, Stirling, Windsor: Britain is studded with castles from vast royal palaces to lonely towers such as Smailholm, Gilnockie or Neidpath. Castles dominate our literature of chivalry from Malory to Bernard Cornwell and, let’s face it – we’d all like one; cold draughty, damp and uncomfortable as they mostly are.

Statue of William Wallace, Aberdeen.

Warfare was, for four centuries after the Norman Conquest, dominated by the perpetual and symbiotic duel between those who built castle walls and those who tried to knock them down. This contest continued until the age of gunpowder profoundly altered the balance. Prior to that, the advantage typically lay with the defender. It is widely believed that it was the Normans, with their timber motte-and-bailey fortifications, who introduced the archetypal castle into England, though some historians now dispute this. During the 12th century, timber was gradually replaced by masonry; great stone keeps such as Rochester, Orford, Conisburgh, Richmond and Newcastle, soared impressively.

The castle was not just a fort; it was the knight’s residence the seat and symbol of his power, the centre of his administration, and a secure base from which his mailed household could hold down a swathe of territory. Castles were both practical and symbolic. The civil wars between Stephen and Mathilda (also known as the Anarchy) spawned a rash of unlicensed building, fuelling the noble threat to crown authority. Castles grew thickest on the disputed marches of England, facing Welshmen and Scots; in the north-west, the mighty red sandstone fortress of Carlisle stood firm, often attacked, never taken; a clear statement to the Scots.

Concentric castles, influenced by Arab and Byzantine models, appeared when Edward I began building his great chain of towering Welsh fortresses. As the country had enjoyed a long spell of peace before that, many lords had invested in what might now be termed ‘makeovers’ – aiming to improve standards of living rather than add to defences. Larger, more ornate chapels and great halls replaced their workaday predecessors; gardens and orchards were laid out to provide tranquil spaces within the complex.

Cross given by Mathilda, Abbess of Essen (973–1011), typical of medieval devotion.

Most castles of the earlier period relied upon the strength of the great keep: towering in fine ashlar with the lower vaulted basement reserved for storage and an entrance at first floor level, frequently later enclosed in a defensive fore-building. On this level, we would typically find the great hall with a chapel and the lord’s private apartment – or ‘solar’ – on the second floor above. Spiral stairs were set in the thickness of the wall leading to a rooftop parapet walk, often with corner towers. The keep – or ‘donjon’ – was surrounded by a strong stone wall enclosing the courtyard or bailey which would also house the usual domestic offices. The keep was essentially a refuge, a passive defence.

From the reign of Henry II onward, strong flanking towers were frequently added to provide defence against mining. The isolated polygonal keep at Orford in Suffolk (1165–1173) is a fine example of this. At Pembroke, William Marshal built an entirely circular keep. The curtain wall was also raised and strengthened, complete with D-shaped towers, the section lying beyond the curtain wall rounded at the corners to frustrate mining. These towers made the attacker’s job far more difficult. If he breached or surmounted, a section of the rampart, he would be corralled between the towers that would, now and in turn, have to be assaulted separately. This was leading toward the concentric design where the strength of the fortress was distributed through the towers and the great keep, as a principal feature, became far less important.

Detail from the Morgan Bible, 13th century.

Traditional timber engines like the ballista and the mangonel dominated siege warfare during the 13th century. The ballista was, in effect, a giant crossbow that hurled a bolt or occasionally stones at the enemy’s walls. It was intended as an anti-personnel weapon, smacking unwary defenders from the parapet, used to cover an assault or ‘escalade’.

Reconstructed Trebuchet at Middelaldercentret, Denmark.

The trebuchet, most likely Arabic in origin, worked by counterpoise. The weapon was built with a central timber beam pivoting between two sturdy posts; one end of the beam had ropes affixed and the sling was fitted to the other. Initially, when the ball was loaded into the sling, a group of hefty squaddies simply hauled on the ropes, pivoting upwards the shorter end of the timber, to ensure the sling, at just the right moment, released the projectile. Latterly the men were replaced by a timber-framed box casing filled with rubble. By now these machines were much larger and the box might weight anything over 10,000 lb (4,536 kg).

Siege

When the knight or castellan became aware that a siege was imminent, it was time to prepare. Clearly, adequate foodstuffs and a clean water supply were essential to maintain the garrison for what might stretch to several months of encirclement. Livestock would be gathered in, and the surrounding countryside stripped to deny the attackers. Ditches would be cleared and consolidated; repairs to the masonry undertaken, trees, bushes and inconvenient settlements would be demolished to deny cover to the enemy. Timber hoardings – called ‘brattices’ – would be erected over the parapet walk to provide a covered fighting platform. The defenders’ own artillery was serviced, repaired as necessary, and supplies of missiles and arrows brought in.

Siege warfare was costly, time-consuming and tedious. The attacker might be stuck before the defences for several long and frustrating weeks, gobbling up his supplies at a fearsome rate, at risk from the defenders’ sallies, from dysentery in the crowded, insanitary trenches or from the arrival of a relief force. He would try to negotiate, to persuade the castellan to come to terms. If the latter acceded before the lines were fixed, convention would allow the defenders to march out under arms and depart unmolested.

If cajolery failed, then threats might suffice. Captives were handy pawns. In 1139 King Stephen persuaded the mother of Roger le Poer to surrender Devizes or see her son hanged before the walls. Edward III, in 1333, before the walls of Berwick, threatened to hang the governor’s two young sons if the gates remained closed. The latter refused and had to endure the agony of watching the wretched youths die. Edward, like his grandfather, didn’t issue idle threats.

If a siege dragged on, any inclination to mercy shrank. Should the place fall to storm then the attacker could put all wi...