![]()

CHAPTER 1

THE LUFTWAFFE VERSUS THE ROYAL AIR FORCE

Operation ‘Seelöwe’

On 4 June 1940, the Battle of Dunkirk was over. The British Expeditionary Force in France had been expelled from the continent by the lightning offensive launched by Hitler in the West on 10 May. Indeed, 338,000 men had been evacuated across the narrow Strait of Dover, but the British Expeditionary Force had lost all its heavy equipment in France.

In the UK, there were exactly 167 anti-tank guns and the heavy military equipment at hand was no more than that normally assigned to two infantry divisions. Almost 1,000 British aircraft had been lost during the Battle of France. 2 On 4 June 1940, RAF Fighter Command mustered no more than 446 operational fighter aircraft, of which only 331 were the single-engined modern types that had any chance to take up the battle with the German fighters – Hawker Hurricane and Vickers Supermarine Spitfire. The words uttered by British Prime Minister, 65-year-old Winston Churchill, in a radio broadcast speech on the same day have become winged:

We shall go on to the end,

we shall fight on the seas and oceans,

we shall fight with growing confidence and growing strength in the air,

we shall defend our Island, whatever the cost may be,

we shall fight on the beaches,

we shall fight on the landing grounds,

we shall fight in the fields and in the streets,

we shall fight in the hills,

we shall never surrender!

At that time, many characterized Churchill as an irresponsible adventurist. But Winston Churchill was not only a ‘fighter’; his resolve to fight on was based on deep psychological insights, and – not least – an understanding of the personalities of two most important statesmen, Germany’s self-willed dictator Hitler and the President of the United States, Franklin D. Roosevelt. When Roosevelt in August 1940 sent an American military delegation for a conference with the highest military command in Britain, the commander of the British Air Staff Air Chief Marshal Sir Cyril Newall, admitted that the US economic and industrial cooperation was the foundation of the entire British strategy.3

Churchill knew that Roosevelt was on his side, but there also was a large isolationist public opinion in the United States who wished the United States to continue to stay out of the war, so it was obvious that Roosevelt could not do much before the presidential elections in November 1940. Thus, everything hung on the British ability to hold out until then. Moreover, Churchill expected that if Britain could hold out until the autumn weather made it impossible to carry out air operations on a large scale, Hitler would lose his patience and turn his attention against Communist Soviet Union, which would be Britain’s rescue. Until then, there were four critical factors that would determine whether Britain would sustain the German onslaught: the will to fight on, the Royal Navy, the Royal Air Force, and whether the British would be able to buy themselves time.

Regarding the first, Churchill personally contributed more than anyone else in reinforcing the British will to resist. When Hitler eventually realized that he needed to use force to subdue Britain, he met a people with dogged resolve to resist. The Royal Navy, their powerful fleet, was still the strongest in the world and still ruled the seas. The third and fourth factors – concerning the air force and time – were closely linked to each other. Britain’s good fortune was, as so often in history, one of geography – that the country is surrounded by sea. With the Royal Navy’s mastery at sea and the Germans in possession of the world’s most effective air force, it was not hard to figure out that the battle would be decided by the outcome of the air war.

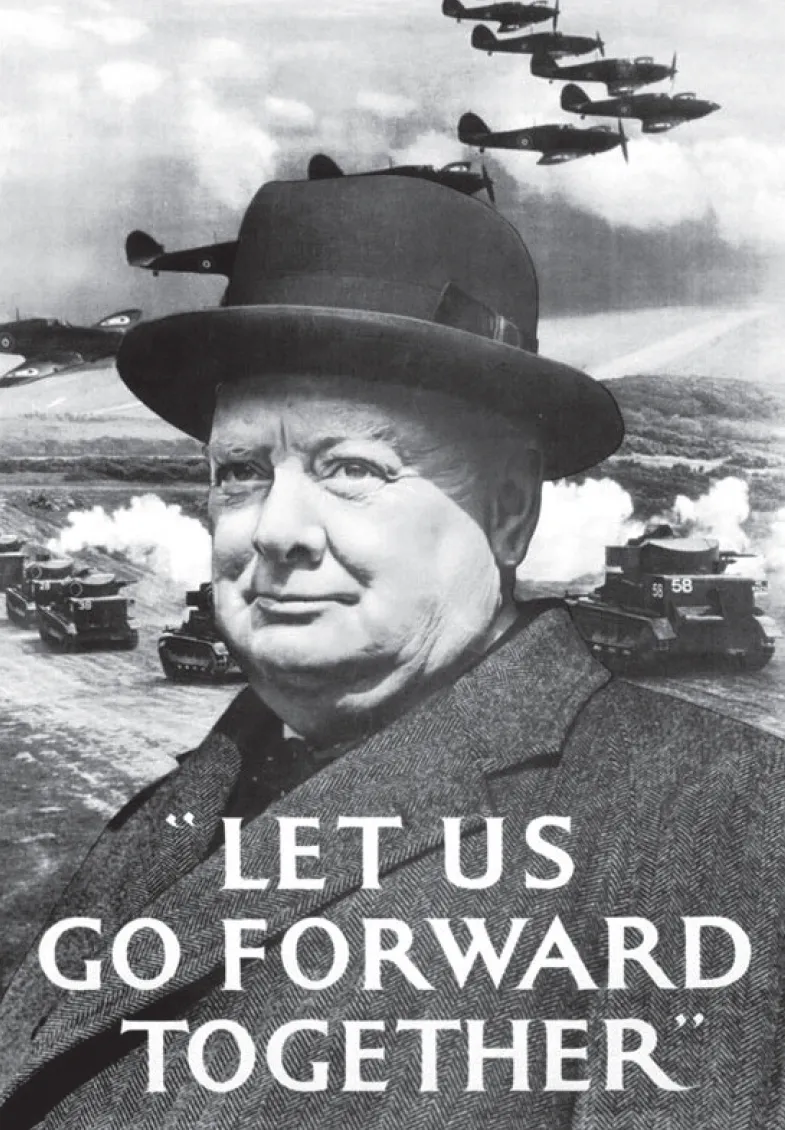

This British propaganda poster from 1940 clearly illustrates Winston Churchill’s prominent role in stoking the British will to resist.

As it would turn out, Churchill in an almost eerie way managed to read the mind of the Nazi dictator. Hitler lived in a world of racist fantasies, and to him it was both unnatural and undesirable to have the two ‘white master races’ – the German and the British people – in a feud with each other. No one could be less prepared for a war with Great Britain than Adolf Hitler.

On 2 June 1940, he had said that he looked forward to a peace settlement with London so that he ‘could finally get his hands free’ for his ‘great and real task: to deal with Bolshevism’. Since Hitler wished to save his armed forces for the latter purpose, he conveyed to the British that he was prepared to accept a separate peace. According to this, Britain would retain its Empire – with the possible exception of the returning to Germany of the small colonies that Imperial Germany had in 1914 – and also its armed forces intact. The only concession that Hitler demanded was, except of course for an end to the fighting, that Britain would recognize the Third Reich’s hegemony in Europe.

While the British were given a few weeks of relative calm, which they used to prop up war production, Hitler showed what can only be described as an apathetic approach towards warfare against Great Britain. On 17 June, a conference at the German Naval Headquarters noted that regarding an invasion of England, ‘the Führer still has not uttered any such intentions,’ while ‘the High Command still has not made any studies or preparation.’4

When France surrendered on 22 June 1940, Hitler regarded the war as largely finished. ‘The Führer really does not wish to put any pressure on the British’, propaganda minister Goebbels noted on 27 June. Hermann Göring, the Luftwaffe’s C-in-C, wanted to get started with air operations against England, but was held back by Hitler.5

Only on 13 July did Hitler care to take a look at the various draft plans for an invasion of England that had been made by the various branches of the Wehrmacht. But he was still hesitant. ‘The Führer’, wrote Generalleutnant Franz Halder, Chief of the German Army Staff, ‘accepts that it may be necessary to force Britain to make peace, but he is very reluctant to take this step because he believes that if we defeat the British on the battlefield, the British Empire will collapse, and Germany would not benefit from that.’

This operations’ plan, originally called ‘Löwe’ (lion), largely called for an amphibious landing on the English south coast over the course of three days with thirteen army divisions – four between Brighton and the Isle of Wight, six between Ramsgate and Eastbourne, and three at Lyme Bay. Once this first assault force had established bridgeheads to a depth of 10-15 kilometres, another twenty-eight divisions were to follow, in order to develop an offensive from these bridgeheads, aiming to occupy the entire United Kingdom. Hitler made only one remark – he changed the code name from ‘Löwe’ to ‘Seelöwe’ (sea lion).

Following Churchill’s rejection of Hitler’s peace offer on 22 July, Operation ‘Seelöwe’ advanced to the highest priority, and the Germans began to look for resources for the invasion. Suddenly there was a rush! It was calculated that ‘Seelöwe’ had to be implemented no later than 15 September 1940, because after that, the autumn weather was assessed to be too uncertain to guarantee the crucial Luftwaffe support of the operation.

Army units were hastily assembled at Pas de Calais, the Seine Estuary and the Cotentin Peninsula. But the German army lacked the necessary sea vessels for an amphibious landing. The kind of landing crafts that the Allies used in the Pacific and during the invasions in Europe in 1943–1944 did not exist. Things had to be improvised. Basically, what the Germans had available for the landing operation was common river barges! In a few weeks, the Rhine and the Dutch channels were cleared of their small coal barges. These took out in their thousands to the North Sea and entered the French and Belgian Channel ports.

Next were the logistical problems. How would half a million combat soldiers be supported on the other side of a sea which would definitely swarm with British battleships, cruisers, destroyers and submarines in the crucial moments? It was obviously out of the question. Therefore, several conditions must be met before a German invasion fleet could be sent across the English Channel. German bombers would have to shield the invasion fleet against British warships. But not least the experience from the air fighting over Dunkirk in late May and early June 1940 had shown that German bombers were relatively easy prey for the RAF fighters. Hence, first of all the RAF had to be neutralised. This too could only be the Luftwaffe’s task. The first step was of course to wipe out Fighter Command.

But even if the Germans succeeded in annihilating the RAF and achieving total air supremacy, it was far from certain that the Luftwaffe would be able to hold the powerful British fleet away from the vulnerable invasion craft and transport ships that were to support the invasion army. Nothing but a totally fearless effort by the Royal Navy could be expected. A failure of the invasion of Britain would likely have far-reaching political consequences; it would be a terrible blow against both German military prestige and Hitler’s political authority. The Nazi leader feared that such a large failure could jeopardize his main war aim, the invasion of the Soviet Union.

Moreover, the aviation that would bear the main burden of the first phase of the Battle of Britain as the Germans envisioned it, was at the time of the surrender of France in need of recovery. During May and June 1940 alone, 1,428 German aircraft had been lost and another 1,916 badly damaged and in need of repairs (the figures include both combat losses and accidents). Although the aviation industry’s output figures roughly kept pace with losses during the Battle of France, the aviation that was so crucial for operations against the British Isles, the bombers, had declined from 1,102 operational aircraft in March 1940 to only 841 in June, thus a reduction of almost a quarter. Another important type of aircraft, transport planes, had been reduced in number by more than a third since the outbreak of war – from 552 to 357. What was expected to be the Luftwaffe’s most important and most difficult task of the entire war – to keep the whole Royal Navy at bay during an invasion of the British Isles – would, even in the most favourable scenario, have been carried out by a further decimated German aviation immediately after the intended final battle with the RAF.

One of the RAF Hurricanes that remained on the continent following the brief Battle of France in May and June 1940. (Photo: Trautloft.)

There were no real plans that showed exactly how the RAF was to be annihilated. It was absolutely clear that the Luftwaffe would not be able to use its full strength as in the Blitzkrieg operations; the geographic distances to various attack targets in and around the British Isles was too large. The single-engined Ju 87 Stukas and Bf 109s were only able to reach the southern parts of England. The Germans had good reason before the war to put the emphasis on the creation a tactical air force, but now they would be forced to use it for a strategic purpose. To top it all, there was no previous experience of this kind of strategic air offensive. The Germans had to invent everything by themselves, through trial and error. No wonder the air operations against England had got off to a very slow start, which was of great benefit to the British.

Relations of strength

By this time Germany and Great Britain had arguably the two most modern air forces in the world. But despite the fact that Germany had begun to expand their armed forces ahead of the UK, the British would surpass their enemy in combat aircraft output figures in 1940. One of the first steps made by Churchill when he was appointed Prime Minister on 10 May 1940, was to make Max Aitken – Lord Beaverbrook – Minister for Aircraft Production. Owing to a combination of state bureaucracy and an unhealthy competition between various private enterprises, British production of the most important fighters was at that time only 144 planes a month. If it had remained at that level, this alone would have been enough to bring the Battle of Britain to a very different ending.

Lord Beaverbrook moved energetically to alter the situation. By putting pressure on the factory owners – including harsh crackdowns on factories that hoarded spare parts and tools, and the expropriation of property that was required – plus a comprehensive and systematic looting of non-airworthy aircraft for spare parts, the previous owner of the Rolls-Royce Automobile Company achieved a miracle with British aircraft production. In June alone, 446 fighters were manufactured. At the same time bomber production also increased to a record of 407. Between 4 June and 10 July – the period of tranquillity that the British were given before the real German air offensive begun – the strength of RAF Fighter Command increased by 68%, from 446 to 656 serviceable fighters. On top of that, a force of 467 serviceable bombers exposed Germany and the occupied territories to regular nocturnal attacks.

However, the RAF was opposed by a force that was more than twice as large. Not only was the Luftwaffe on the whole superior to the RAF in terms of aircraft quality, but it also enjoyed a more than satisfactory numerical advantage. In June 1940 the Luftwaffe had 2,295 operational combat aircraft at its disposal – 841 bombers, 337 dive-bombers and assault aircraft, and no less than 1,117 fighters (856 Bf 109s and 261 Bf 110s). 6

But time was on the side of the British – and this in more than one respect. The Luftwaffe was indeed more powerful than the RAF, but British aircraft production already exceeded that of Germany. Hitler’s idea of the German people’s grandeur frequently led him to decisions that went counter to the war plans. Such was the case with his decision not to set the country on a total war footing, but instead maintain civilian production at a high level.

When the Battle of Britain began, the Luftwaffe really had too few of the two aircraft that were most critical to the new strategic air operations over the British Isles – the bomber Junkers Ju 88 and the fighter plane Messerschmitt Bf 110. These the two most modern aircraft in the Luftwaffe inventory were the only ones with a sufficient operational range to reach every corner of the British Isles. Although the Ju 88 received the highest priority in German bomber production, with almost two-thirds of all new bombers in 1940 being Ju 88s, it still only was 1,816 out of a total 2,852, while at the same time British output was 3,488 bombers, this in a year when fighter production received the highest priority!

Of the twin-engined Bf 110 fighters, no more than an average of 102 a month were manufactured. For this simple reason, it would be an air offensive against England rather than Great Britain, which gave the RAF the opportunity to withdraw worn-out units to tranquil regions further north in order to rest and refit. Had there been Bf 110s in large numbers, the RAF would not have had this great advantage. While Germany throughout 1940 produced 3,106 Bf 109 and Bf 110 fighters, the British produced 4,283 fighters. During the critical four-month period of June-September 1940 alone, output figures from British aviation industry were 1,743 fighters, while another 1,872 fighter aircraft were repaired.

Of equ...