![]()

1

PRINCIPLES OF U-BOAT LOSS ASSESSMENT DURING WORLD WAR II

While the U-boat war against the merchant shipping of the Allied nations on the transoceanic communication lines became a centerpoint in the German naval strategy of World War II, the number of U-boats sunk in battle was an important measure of success in the worldwide Allied campaign against the German U-boats. Especially after the defeat of the German U-boat offensive against the transatlantic convoy traffic in May 1943, the destruction of the U-boats themselves more and more became the primary objective of the Allied antisubmarine forces. Although the German U-boat Command tried to get a maximum of information on the times and causes of individual U-boat losses during front-line operations, the actual results were often not satisfying. The reasons for the failure to achieve better intelligence on U-boat losses, however, were inherent to the U-boat warfare.

The extent of tactical command exercised by the German U-boat Command on the operations of individual boats at sea was limited. Commanding officers of U-boats ordered to patrol independently on the shipping lanes in distant areas off the American and African Atlantic coasts or in the Indian Ocean assumed a maximum of tactical freedom in the conduct of their patrols. The role of U-boat Command was limited to the allocation of general operational areas or focal points and the eventual supply of additional information on the enemy (shipping routes, sightings, etc.). Even during group operations against Allied Atlantic convoys, the control of individual boats mostly concentrated on the direction of search operations until contact with the enemy had been established.

Apart from boats engaged in running convoy operations, U-boats on patrol normally took great care to remain unobserved at least until the first attack. Out- and inbound boats were to send a short signal when certain lines along their passage routes had been passed in order to allow U-boat Command any further disposition of the boats at sea. Until the autumn of 1944, U-boats outbound from French bases into the Atlantic normally transmitted a passage report between the longitudes of 15° to 18° west, whereas boats from German or Norwegian bases directed into the Atlantic normally signalled after a successful break through the passages north of Britain. Inbound boats usually reported their appearance at the rendezvous points off the various bases between twenty-four and seventy-two hours in advance to make allowance for the preparation of harbor escorts.

Simultaneous with the introduction of the schnorkel and the beginning of continuous submerged patrols in the inshore billets around Britain and the North American coast from autumn 1944 onward, a major change compared with the previous German practice in the use of radio signals took place. Fearing the now-known dangers of being monitored by ship or shore-based Allied radio direction-finding systems, it became normal practice that a U-boat only reported twice during its entire patrol. Usually the first report consisted of a passage report sent to indicate the successful outbound trip around the north of Britain into the Atlantic. The second message was a situation report about the operational area and any successes, also indicating that the boat had left its operational area to return home. This practice resulted in long periods of strict radio silence that could last for many weeks.

In general, U-boat Command was often unaware of the state of the individual boats during their patrols. The presumed rough positions of the operational boats were plotted on a daily basis to allow for a limited overview of the U-boat disposition. Where possible, information drawn from monitoring enemy signals was related to individual U-boats. Therefore, it is not surprising that some U-boats were still believed to be operational by U-boat Command although they had been sunk weeks before. In the case of U 863, its loss was finally established four months after the actual date of loss.

Usually losses became apparent when a U-boat remained silent for a longer period or failed to signal upon direct orders from U-boat Command. Under these circumstances, it was advised to radio its position or to transmit a short weather report without delay to verify its existence. As atmospheric or tactical conditions might prevent boats from receiving or sending messages, U-boat Command repeated such radio orders at least three times over a period of several days. Even when no answer was received, U-boat Command often continued to plot overdue boats in the daily dislocation for up to several weeks because there was still the possibility of a radio station breakdown. In many cases, boats were plotted until they theoretically would have run out of fuel and provisions. However, despite the very careful procedure to establish losses, there were a few cases when U-boats were wrongly considered as lost but did make a report later or entered base afterward without prior notification. In each case, radio problems were identified as the reason for the failure to report after repeated orders from U-boat Command.

Sometimes U-boats were able to transmit a final radio message prior to their sinking or friendly forces were on the scene and could pick up survivors. The latter was a very rare case because German U-boats operated almost exclusively in distant, enemy-controlled waters without any assistance from their own surface forces or aircraft. Crew members surviving the loss of their boat were normally picked up by Allied forces and became prisoners of war.

When a loss became evident but had not yet been confirmed from other evidence, the boat in question was officially posted as missing. In German naval terminology, this meant the attribution of a “one star” mark indicating a probable loss. Almost each U-boat loss was discussed in some detail in the war diary of U-boat Command on the basis of the available evidence, trying to establish the probable date and cause of the loss. Starting from late 1941, summary lists of U-boats lost during individual months together with statistical information were appended to the U-boat Command war diary. Up to March 1944, the operational department of U-boat Command also prepared a summarized report on the final patrol of each U-boat lost during front-line service, based on orders and radio messages and information derived from sinking reports, interception of Allied ASW reports, and so on. Owing to a lack of proper intelligence sources, U-boat Command gained no exact information on the date or cause of loss in more than 60 percent of the front-line U-boat losses.

Positive confirmation for a U-boat loss sometimes became available via the International Red Cross, which, under the Geneva Convention, usually received the names of those taken as prisoners of war by the belligerent parties. Often the hull numbers of U-boats sunk together with the number or names of surviving crew members were broadcast in the Allied news propaganda. In addition, prisoners of war of a sunken U-boat were sometimes able to report details about its loss to German authorities by using coded words in private letters to their next of kin.

When the final fate of a missing U-boat had become known or no clue about its fate and its crew had been established after sufficient time, the boat was assigned a “two star” mark and the case was officially closed by the operations department of U-boat Command.

The Allies were in a much better position to gain information on the causes of U-boat losses. The British Admiralty had set up the special U-boat Assessment Committee immediately after the start of the war. Committee members represented the different armed services and Admiralty departments involved in the antisubmarine campaign. The main objective of the committee was to centralize the assessment of all antisubmarine actions performed by British naval ships and aircraft. After the entry of the United States into the war, the U.S. Navy had set up a similar committee under the authority of the commander in chief U.S. Navy (Cominch). By agreement with the British Admiralty, Cominch became the assessing authority for all antisubmarine attacks by U.S. forces and the Admiralty for British and Commonwealth forces.

Each attack against a submarine target had to be reported to the committees with all details and postattack observations on special forms together with any other available evidence to verify the presence of a submarine and to assess the damage inflicted by the attack. Additional evidence could include action photographs taken during or after the attack. Surface ships often provided oil samples or pieces of wreckage picked up after their attacks. Sometimes even more gruesome evidence was presented to confirm a successful attack against a submerged U-boat.

Every reported attack was discussed and assessed within a few weeks by the committees in their regular meetings. A letter was assigned to each case indicating its situation. Standard assessments adopted by the Admiralty and Cominch are listed below with the letters given to them:

1. Assessment of “A” (known sunk) was not awarded unless positive proof of destruction had been obtained. Submarines very rarely sink without a trace, and the collection of surface evidence, prisoners, wreckage, human remains, and such things, is the only reliable proof of a sinking.

2. Assessment of “B” (probably sunk) was awarded when the committee felt morally convinced that the submarine was destroyed, but lacked concrete evidence of a corpus delicti.

3. Assessment of “C” (probably damaged) was awarded to promising attacks that were believed to have damaged the submarine seriously, and that may have proved fatal, but on which an assessment of “B” or “A” had not been given pending receipt of further intelligence justifying a higher assessment.

4. Assessment of “D” (probably damaged) was awarded to attacks that were believed to have damaged the submarine sufficiently seriously to force it to return to base.

5. Assessment of “E” (probably slightly damaged) was awarded to attacks that were believed to have caused material damage of such a character as to hamper the submarine in the further prosecution of its patrol.

6. Assessment of “F” (insufficient evidence of damage) was awarded to those attacks that gave insufficient evidence of damage to the submarine believed to have been present.

7. Assessment of “G” (no damage) was awarded to those attacks that could have caused no damage to the submarine believed to have been present.

8. Assessment of “H” (insufficient evidence of presence of submarine) was awarded to those attacks that gave insufficient evidence of the presence of a submarine.

9. Assessment of “I” (target attacked not a submarine) was awarded to those attacks where the target was definitely nonsubmarine.

10. Assessment of “J” (insufficient information to assess) was awarded to those attacks concerning which no letter reports had been received, and when the dispatches were too indefinite to evaluate.

The results from precision raids or area bombing attacks against German U-boat construction sites or base and harbor facilities were independently assessed from aerial photographs by the photo interpretation units of the RAF Bomber Command and the USAAF.

The assessment of the individual damage inflicted by antisubmarine attacks offered many possibilities for misinterpretation and error. The simple fact that submarines unlike surface ships can submerge below the water surface without necessarily being considered as sunk is one of them. Attacks against submarines staying submerged are even more problematic as all action is directed against an invisible target hidden in a medium almost impenetrable by the human eye. Additional difficulties arose from the numerous attacks on nonsub contacts. With the German policy of “Total Underwater War” adopted in autumn 1944 after the introduction of the schnorkel installation, the assessment committees were faced with the problem that many of the attacks reported were probably not directed against genuine U-boats. The schnorkel had reduced the silhouette of a patrolling U-boat at best to an elusive schnorkel head sticking out of the water from time to time. Especially among aircraft crews employed in AS-sweeps, this resulted in a kind of “schnorkelmania” during the final year of the anti-U-boat campaign. The actual extent of these “bogus” sightings and related attacks against nonsubmarine contacts by Allied aircraft was realized several years after the war. Many of the U-boat schnorkel contacts reported were actually meteorological phenomena such as whirlwinds (whillywaws) or spouting whales.

![]()

2

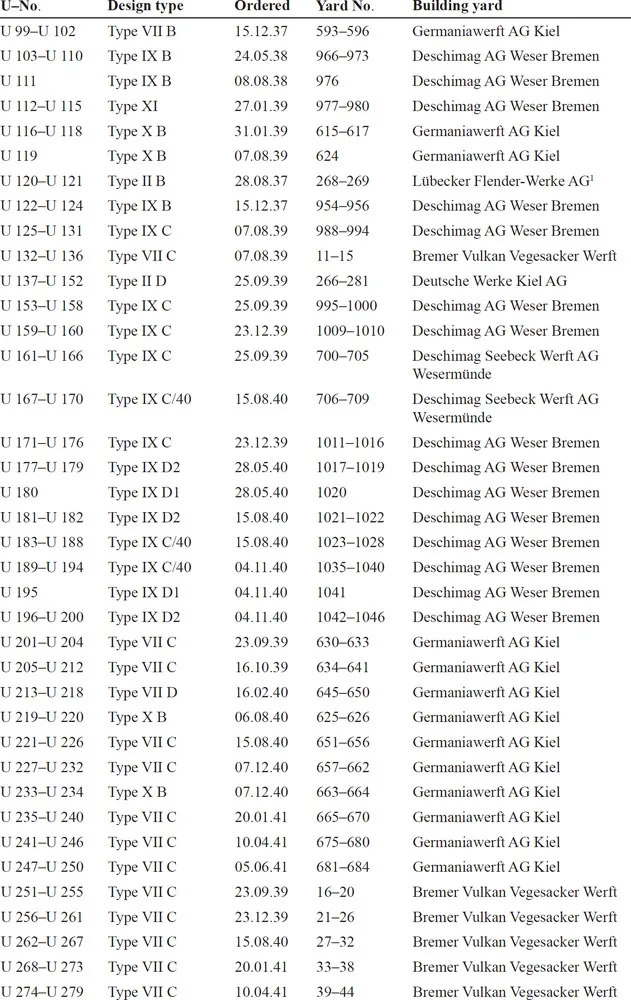

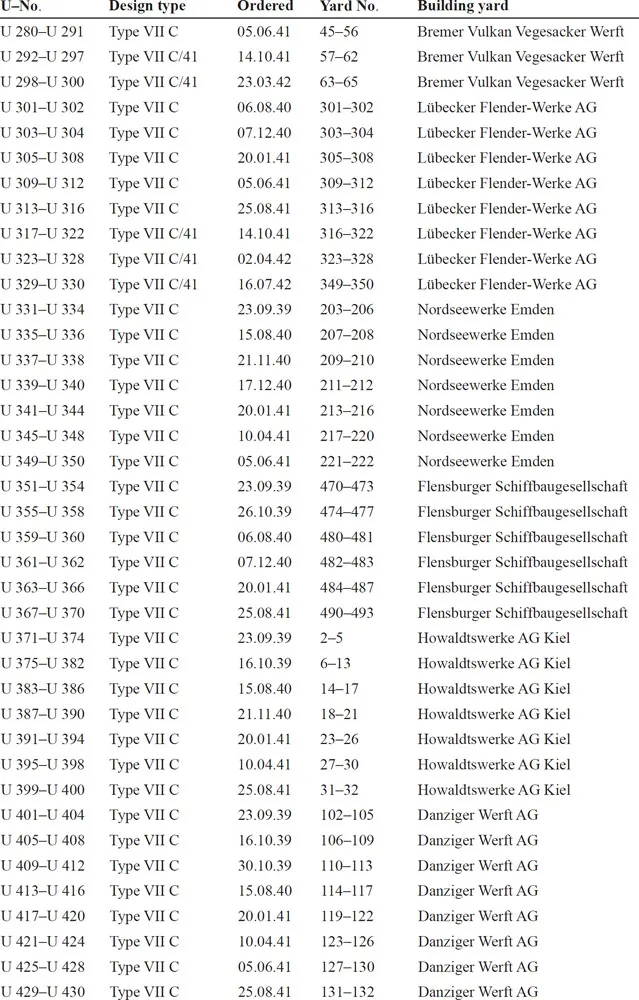

GERMAN U-BOAT NUMBERS AND TYPES, 1935–1945

All U-boats contracted or impressed by the German Kriegsmarine between 1935 and 1945 are listed. Missing U-numbers indicate that for various reasons no building contract was placed for these U-boats.

![]()

![]()

![]() 2323__perlego__chapter_divider_...

2323__perlego__chapter_divider_...