![]()

PART I

MOTIVE

![]()

CHAPTER

1

PETROLEUM MAN

Global demand for oil and natural gas is growing faster than new supplies are being found, and the world population is exploding. Currently the world uses between four and six barrels of oil for every new barrel that it finds, and the trend is getting worse.1 Natural gas use is exploding while the rate of new gas discoveries (especially on the North American continent) is plunging.2

According to most experts — including Colin Campbell, one of the world’s foremost oil experts with decades of experience in senior geologist, upper management, and executive positions with companies including BP, Amoco, FINA, and Texaco — there are only about one trillion barrels of accessible conventional oil remaining on the planet.3 Presently the world uses approximately 82 mb/d (million barrels per day). Even if demand remained unchanged, which it clearly will not, that would mean that the world will run out of conventional oil within thirty-five years. Oil, however, does not flow like water from a bottle. Since the world’s population and the demand for oil and natural gas are increasing rapidly, by reasonable estimates, the world supply of conventional oil is limited to perhaps 20 years. It’s a common mistake to assume that oil will flow in a steady stream and then suddenly stop one day. Instead, the stream will gradually diminish in volume, with occasional small increases, even as the number of people “drinking” from that stream, and the amount they consume explodes.

Other issues compound the problem. As fields deplete, oil becomes increasingly expensive to produce. These costs must be passed on to consumers.

Not all oil in the ground is recoverable. When it takes more energy to pump a barrel of oil than is obtained by burning it, the field is considered dead, regardless of how much oil remains. Unconventional substitutes are extremely expensive and problematic to produce. Tar sands, oil shale, deep water, and polar oil sources have severe limitations. Canadian tar sands development is proving disappointing because it requires large quantities of fresh water and natural gas to make steam, which is a necessary part of the extraction process. Natural gas cost and fresh water shortages are already limiting production, and the material costs for the energy needed to make the energy have already begun to curtail production.

The same problems afflict the development of shale, deep water, and polar reserves. They are currently too expensive to develop in quantity, and when exceptions arise, they’re too small to mitigate Peak Oil. Even the best-case “fantasy” scenarios for these energy sources don’t change the picture much. To learn more about this I recommend two web sites: <www.peakoil.net>, and <www.hubbertpeak.com>.

I’m capitalizing the phrase “Peak Oil” to indicate that it’s a historical event. It’s an unavoidable, utterly transformative crisis, and an increasing body of evidence suggests two major consequences. I’ll state them here in the starkest terms; later I’ll add reassuring qualifiers and a few formulations that might be more palatable. But it comes to this: first, in order to prevent the extinction of the human race, the world’s population must be reduced by as many as four billion people. Second, especially since 9/11, this reality has been secretly accepted and is being acted upon by world leaders. In this chapter I marshal the evidence for this disturbing pair of hypotheses which, taken together, constitute the ultimate motive for the attacks of September 11th, 2001.

What have hydrocarbons done for you lately?

Oil and natural gas are close cousins. In nature the two are often found very close together because they can originate from the same geologic processes, under conditions that have existed only rarely in the Earth’s four-billion-year history. Oil and gas are hydrocarbons that come from dead algae and other plant life. There are biological traces in oil proving that it came from living matter.4 Since the earth is a closed biosphere, oil and gas are finite, non-renewable resources. The world has used half (if not more) of all the hydrocarbons created over millions of years in just about one hundred years.5

According to Richard Duncan, PhD in 1999 approximately 95 percent of all transportation was powered by oil. And 50 percent of all oil produced is used for transportation purposes. No other energy source even comes close to oil’s convenience, power, and efficiency.6

Oil pervades our civilization; it is all around you. The shell for your computer is made from it. Your food comes wrapped in it. You brush your hair and teeth with it. There’s probably some in your shampoo, and most certainly its container. Your children’s toys are made from it. You take your trash out in it. It makes your clothes soft in the dryer. As you change the channels with the TV remote you hold it in your hands. Some of your furniture is probably made with it. It is everywhere inside your car. It is used in both the asphalt you drive on and the tires that meet the road. It probably covers the windows in your home. When you have surgery, the anesthesiologist slides it down your trachea. Your prescription medicine is contained in it. Your bartender sprays the mixer for your drink through it. Oh yes, and the healthy water you carry around with you comes packaged in it.

Be careful. If you decide that you want to throw this book out, your trashcan is probably made from it. And if you want to call and tell me what a scaremonger I am, you will be holding it in your hands as you dial. And if you wear corrective lenses, you will probably be looking through it as you write down a number with a pen that is made from it. Plastic is a petroleum product, and its price is every bit as sensitive to supply shortages as gasoline. Oil companies do not charge a significantly different price for oil they sell to a plastics company than they charge a gas station owner. If the wellhead price goes up, then every downstream use is affected.

If you live in the United States and the power generating station that serves your community was built within the last 25 years, natural gas is probably providing you with the electricity that powers the bulb illuminating this book. According to figures supplied by the US government, some 90 percent of all new electrical generating stations will be gas powered. Vice President Cheney’s “energy task force,” the National Energy Policy Development Group (NEPDG), stated in summer 2001 that “to meet projected demand over the next two decades America must have in place between 1,300 and 1,900 new electric plants. Much of this new generation will be fueled by natural gas.”7

Oil is also critical for our food supply. Quantitatively speaking, modern food production consumes ten calories of energy for every calorie contained in the food.8 When the farmer (or more likely the “agribusiness employee”) goes out to plant seeds, she drives a vehicle powered by oil. After planting she sprays the crop with fertilizers made from ammonia, which comes from natural gas. Then she sprays them several times with pesticides made from oil. She irrigates the crops with water that most likely has also been pumped by electricity generated by coal, oil, or gas. Oil powers the harvest, transportation to processing plant, processing, refrigeration, and transport to the grocery store (to which you, the consumer, drive an oil-powered vehicle).

You may pay for it with a piece of oil that you carry around in your wallet. Then you take it home, cook it by means of either electricity or natural gas, and eat it on a plate that may have been made from oil, after which you wash the plate with a synthetic sponge that is also made of oil.

Consider this: out of six and a half billion people, there are about four billion who don’t have, and who want, all of the things I have just described. The current world economy is inherently committed to endless growth, and while physically impossible, this illusion is to be chased after by driving the poor countries into a globalized market for cheap goods. Haiti, for instance, has had its domestic rice farming ruined by American export dumping. When the Haitian farmers could no longer underbid the American rice in Haitian markets, they moved off the land and became urban unemployed. Then the Americans raised rice prices to crippling levels. So Haiti is a captive market, but it’s a market nonetheless. Similar developing countries are slowly acquiring more purchasing power and the industrialized world is gaining a foothold in their domestic economies by targeting them for cheap exports. One way or another, the have-nots must become consumers.

Food

How important are hydrocarbons to food production? One recognized oil expert puts it this way: “If the fertilizers, partial irrigation, and pesticides were withdrawn, corn yields, for example, would drop from 130 bushels per acre to about 30 bushels.”9 That’s bad news in more ways than you can think. The same applies in varying degrees to any crop: wheat, alfalfa, lettuce, celery, onions, tomatoes; anything that commercial agriculture produces. Oil and gas are irreplaceable if the world is to continue pumping out enough food to feed 6.5 billion people. And that says nothing about the additional 2.5 billion that are projected to be here before the middle of this century. Organic farming or permaculture is responsible and respectful of nature and may ultimately be nearly as productive as hydrocarbon-based agriculture. But the infrastructure is not in place to implement it. You could ask several billion people to stop eating for a year or two while we switch over and work out the bugs. Do you want to volunteer? Would you volunteer your children?

So what about all the beef cattle, pigs, and chickens that feed on grain and corn? Would you be prepared to pay $50 for a Big Mac if there were severe grain shortages? How about a $25 chicken breast? That would be a quality problem for an American, as opposed to someone in Africa or Asia who lived off of crops and food products sold by globalized agriculture in case there was nothing locally grown. You have always been told that these people just weren’t as productive as we are. It’s not true; they don’t have the oil and the natural gas that we do. The United States contains 5 percent of the world’s population and currently consumes 25 percent of the world’s energy.10

Growth

Oil also powers more than 600 million vehicles worldwide.11 Would you pay for a $50,000 car and pay $5 a gallon for gas? $10 per gallon? Could you? In the current financial paradigm, the stability of the world’s economy depends upon growing revenues through the sale of more and more vehicles and other products that are useless without hydrocarbons. The revenues generated by current customers in developed countries won’t be enough to sustain future growth, so cars and computers and air conditioners are beginning to flow into the new markets of China, Asia, and Africa. Those populations don’t have these energy-guzzling machines (nor the myriad petroleum-derived plastic consumer goods enjoyed in the relatively high-wage countries), but they quite clearly desire them — especially the younger generation, whose purchasing power is growing at the fastest rate. As their economies grow more robust, wages rise and the consumers’ desire becomes actual economic demand.

For the moment, much of the developing world remains ravaged by massive, artificially engineered debt to the World Bank and the IMF. But rising literacy rates and the correlative falling birthrates in many regions promise a massive expansion in consumer spending.12 And this has already begun: Chinese auto sales are exploding. According to one report, 2002 Chinese auto sales jumped by more than 50 percent.13 GM’s auto sales in China jumped by 300 percent in 2002 alone.14

If there is no growth in revenue for the corporations that make and sell these things, then what is left of your 401(k) plan will be worthless. And you might even be out of a job yourself.

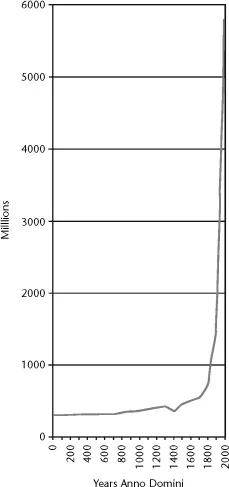

Colin Campbell has rightly identified a subspecies of Homo sapiens that he calls Petroleum Man. He provided me with this population graph that shows the effect of hydrocarbons on the planet since their introduction. The little dip around 1400 was caused by the bubonic plague.15

A number of environmentalists have been sanely and prophetically decrying the destruction of the biosphere for decades. This is another key part of the equation. They have pointed to alternative energy supplies such as wind, solar, geothermal, and biomass as steps toward protecting the ecosystem. But very few understand the infrastructural problems that must be addressed if the crisis is to be solved in any rational manner. Peak Oil will likely turn human civilization inside out long before global warming does, unless — and there are signs that this is happening — oil and gas shortages elicit a tragically shortsighted return to coal.

Given the hundreds of thousands of non-combatant deaths in the resource wars of Afghanistan, Iraq, and so many other places; given the deaths in Europe and Asia from extreme weather conditions in both summer and winter months; given the murderous, smoldering conflict in Nigeria and other oil-rich countries where corporate power combines with the forces of local warlords; given all this, Peak Oil is killing us now. That, and the argument that these are the merest hints of what Peak Oil is going to bring, is the message of this book.

Making rational assessments

As I traveled throughout the US, Canada, and Australia in 2002 giving my lecture called “The Truth and Lies of 9/11,” I ...