1

Cross-Border Access and Exchange of Digital Evidence: Cloud Computing Challenges to Human Rights and the Rule of Law

SABINE GLESS AND PAULINE PFIRTER*

I.Introduction

For many, the move towards an increasingly digital world is looming with dark clouds. Is the threat scenario particularly real for governments? Slogans implying that cyberspace is at the same time ‘everywhere and nowhere’1 and that ‘data is different!’2 make the analogue world look like an easy place to govern. Central to the concept of governance are the rules establishing state authority based on territorial jurisdiction, which have been in place for centuries despite a long history of armed conflict.3 Historically, domestic regulation has governed people’s daily lives and those who were compliant would in return be safeguarded by the rule of law. That ‘no freeman shall be taken or/and imprisoned or disseised or exiled or in any way destroyed, … except by the lawful judgment of his peers or/and by the law of the land’4 is often seen as a guarantor for trial by jury or a bulwark against discrimination.5 However, with respect to international criminal justice the relevant question becomes whether ‘(s)he who is subject to English law, is entitled to its protection’?6 Or could any equivalent legal system suffice?

When governments seek the cooperation of other external legal entities, for instance to prosecute an alleged criminal, they use well-established channels of mutual legal assistance (MLA) and are careful to abide by the principle of non-interference (sovereign states shall not intervene in each other’s affairs), thus respecting each other’s rule of law.7 In theory, local governments have exclusive authority over their respective states and citizens. This territorial state monopoly on the use of force obviously has been blurred during recent decades, for instance by mutual recognition of judicial decisions as practised in the European Union with the implementation of practices such as the European Investigation Order (EIO).

Increased digitalisation now causes more turmoil for traditional means of governance and the relationship between a citizen and the state. While the process of establishing states took centuries, within a few years global digital giants have invented a business model of cloud computing that has changed the conduct of business in a large number of companies and in many states as well. Nowadays, businesses and people outsource numerous daily activities to cloud systems. The vast majority of people have access to at least one cloud-based platform, but very few probably give much thought to the underlying technology, or legal implications of their actions. Cloud-based platforms promise not just more, but also different types of freedom through their large computational power and ability seemingly to extend beyond sovereign borders.

This chapter discusses the challenges of the digital era in cross-border investigations for traditional criminal justice notions of individual judicial rights. Until now, even within the close-knit community of the EU Member States, exchanges of evidence still required the assistance of the domestic authorities in the state where the evidence was obtained. Nonetheless, the e-evidence package proposed by the Commission – and, at the time of writing, under negotiation8 – will streamline access to information stored in a cloud by creating instruments for direct and mandatory cross-border cooperation. The package is similar to legislation already adopted by the United States, the so-called CLOUD Act.9 This chapter offers a critical overview of these legislative developments from a human-rights and rule-of-law perspective.10 To that end, it first explains the traditional functions of cross-border evidence sharing and the challenges faced by increased digitalisation; the chapter then scrutinises the EU and US approaches to cross-border evidence transfer regarding information that must be obtained from a cloud system, with a focus on the preservation of individual rights in the digital age. It is argued that these new legislative approaches on both sides of the Atlantic put traditional principles of MLA at risk by allowing direct cross-border access to information from cloud computing without protection for individual rights, particularly the right to respect for private life.11 In light of the above, the following underlying question becomes apparent: Should information be handled differently in a cross-border exchange just because it is comprised of ‘0s’ and ‘1s’ and is stored in the cloud?

II.Cross-Border Access to Evidence Stored in the Cloud

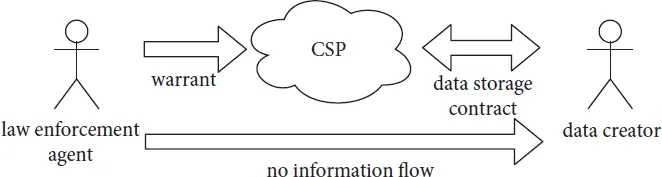

Cross-border exchanges of evidence are necessary in criminal investigations involving more than one jurisdiction. Exchanges have traditionally relied upon a complex system of MLA treaties between governments, ensuring the integrity of principles such as non-interference, protection of individual rights and adherence to the domestic rule of law.12 With the advent of the cloud business model, the framework around the exchange of information necessary to criminal investigations has changed and territorial rulers no longer seem to be the gatekeepers for access; instead, this function is now performed by cloud service providers (CSPs).

At first glance, the extent of the changes resulting from increased use of cloud computing is difficult to capture. Technically, the term ‘cloud’ represents a model of computer data storage and/or processing power whereby the data is stored in different server pools without specific knowledge on which hardware the data is actually stored and processed. These scalable pools are provided via the Internet that may include multiple servers – sometimes multiple locations unknown to the user – and the physical environment is typically owned and managed by a hosting company, the CSP.13 From an economic standpoint, cloud systems are shifting away from computing as a product that is purchased with hardware to computing as a service that is delivered to consumers through a CSP. This results not only in a less expensive service for the consumer, but also in increased difficulty for state authorities – or others – to control the content. Specifically, it presents challenges in a criminal investigation as governments and their law-enforcement authorities require access to certain information irrespective of where and in what format it is stored. While direct access through a CSP seems an obvious way of obtaining such information, the law is unclear as to how compulsory measures can be enforced against CSPs and whose domestic laws apply to data that is stored in server pools that cannot be specifically singled out and identified. As a result, many questions arise: Whose procedural code sets the standard for production orders? Whose standards apply on the protection of individual rights, for instance the right to respect for private life? And whose rights prevail when someone objects to the seizure of data?

Figure 1.1 CSP in the middle of a data collection process in a criminal investigation14

Law enforcement and legislators in many countries have experimented with different approaches to this issue.15 Among other things, the current debate highlights the weakening of state power and the shift of authority from states to private entities who are increasingly setting the standards for the use of information technology.

In many respects, cloud usage mirrors change across the world. As CSPs open the door to global data storage and communication outside state control, they also invite non-traditional forms of supervision and other geopolitical risks. The complicated interplay between individual rights, operational policies of powerful corporations and state authorities – particularly law enforcement – was exposed during the FBI–Apple encryption dispute,16 the Facebook–Cambridge Analytica data scandal,17 Amazon removing Wikileaks from its cloud environment18 and Twitter correcting tweets concerning ballot-by-mail and voter fraud in a heated political debate.19 It is against that backdrop that one must assess the value of new instruments that allow cross-border access to digital evidence,20 particularly in light of demands for regulation around the collection and exchange of information that seek to provide legal certainty for both users and CSPs.21

A.Cloud Computing v Traditional MLA Frameworks

In order to understand whether cloud computing requires specific regulation concerning the exchange of evidence across borders and the potential impact of this type of reform on individual rights and the rule of law, a more detailed explanation of the relevant terminology is required. As such, the terms ‘cloud computing’ and ‘digital evidence’ are discussed below, in addition to their effects on the current legal regime.

i.Cloud Computing

Cloud computing services are (public or private) technical tools offered by a CSP or sub-provider via the Internet that are not bound by national borders, though connected to a state through their place of incorporation. Cloud computing services offer access to digital storage, processing power and services to facilitate user needs by handing over the safekeeping and accessibility of digital information to the CSP rather than storing data in a single local server.22 Current cloud computing solutions regularly offer several gigabytes of free data storage accessible through the Internet from anywhere globally, with no ties to any specific state.23 Cloud computing services may be provided in the form of software-as-a-service (SaaS), platform-as-a-service (PaaS) or infrastructure-as-a-service (IaaS).24 All three types of services use pools of servers located worldwide which are regularly free from any direction from a main server in a single state. It is often the case that the single sub-service provider does not know where the servers for its service are located. This makes it almost impossible to pinpoint a host service – and the information stored therein – to a specific state. As a result of these distributed systems, information may potentially be stored in several locations at the same time and be broken down into bits and bytes without the knowledge of either the service provider, or the data owner.25 In essence, a cloud computing service is nothing more than a new kind of business model for storing and accessing information. While the scope of the service may differ from one CSP to another, they all provide access via the Internet at any given time and place. As a result, any of the stored information may hypothetically be retrieved and, if necessary, be presented in a criminal investigation as digital evidence.

ii.Digital Evidence

Any information used in a criminal investigation, or presented in court in support of fact-finding, is considered evidence.26 Where such evidence is stored or transmitted in digital form – and deemed probative – it is considered digital evidence.27 Examples of digital evidence may include text messages, metadata embedded in documents, access log files from a service provider – cloud-based or otherwise – information regarding sent and received emails, information about IP addresses associated with downloads, or information provided through malware.28 Digital information – regardless of the cloud computing service (SaaS, PaaS or IaaS)29 – is stored without a fixed connection to a single server, and ...