![]()

Nodes in Alphabetical Order

A Foot in Each World

Counterintuitive behavior

Common sense and agora-savvy would seem to indicate that the individual person who feels completely at home in more than one verbal marketplace must be rare indeed. Of course, the Pathways Project actively encourages citizenship in multiple agoras (Citizenship in Multiple Agoras) as a way to avoid agoraphobia (Agoraphobia) and culture shock (Culture Shock). But full fluency—full media-bilingualism or even-trilingualism—is another matter. Cognitive habits run deep, as we textualists (Ideology of the Text) can come to realize if we’re willing to look beyond our buried assumptions and conditioned reflexes about media.

Occasionally, though, we do encounter an exception that proves the rule: an individual who somehow manages to transact verbal business equally well in two different marketplaces. More than simply getting along in another, “nonmother” medium, such individuals fluently understand and fluently manage more than one cognitive technology. Because they live and act and communicate outside the monomedium paradigms that restrict most of us, they truly do qualify for more than just multiple citizenship. Wherever they’re located at any given time, they have a foot in each of two worlds.

Nikola Vujnovi

The famous expedition to study South Slavic oral epic in its natural setting, conceived and carried out by Milman Parry and Albert Lord, could not have happened without the invaluable and often underappreciated contribution of Nikola Vujnovi

. For Vujnovi

was that rare individual: a person with a foot planted securely in each of two worlds. A performing

guslar himself, he sang a number of epics that were recorded acoustically or via dictation for the American scholars. But he also had enough literacy to be able to write down other poets’ performed epics from dictation.

What did this native experience in both the oAgora and tAgora mean? Much more than a mere translator between languages, Vujnovi

served as a fully credentialed guide and intermediary between cultures and between agoras. On the one hand, he understood the South Slavic oral epic tradition from an insider’s point of view. After all, he was himself a member of that epic tradition. As a

result, he was able to interview other

guslari as a colleague whom they could trust and respect.

But there was another, complementary side to Vujnovi

’s crucially important role. To the oral world of the epic bards he could also bring inquiries conceived in the world of writing, reading, and texts (Arena of the Text), translating his employers’ questions about South Slavic epic, Homer, and oral tradition into terms the other singers could grasp.

Still another benefit of his serviceable literacy emerged later on, when Lord brought him to the Parry Collection1 at Harvard University to transcribe the oral epics they had recorded acoustically on large aluminum disks. Indeed, it seemed the perfect situation: a transcriber who was not only steeped in the epic register but also himself a guslar. And in many ways it was an ideal arrangement, although not in every respect. But that’s another story (Singing on the Page).

If there were ever any question of whether a single individual could acquire native fluency and profitably use it in more than a single agora, Nikola Vujnovi

certainly provides a “textbook” answer.

Paolu Zedda

The island of Sardinia boasts a vigorous tradition of competitive oral poetry that reaches back for many centuries. Similar in its general outlines to Basque bertsolaritza and numerous other contest-song traditions worldwide (including some conducted via the Internet),2 this genre of verbal dueling, called mutetu longu by the community, customarily involves from three to six poets. The duelers take turns “fighting” one another by improvising short poems, back and forth, on an assigned topic over a two- to three-hour period. The audience includes long-time aficionados who sit close to the action (often with recording equipment to preserve these improvised creations), as well as a cross section of the community somewhat more removed, physically and interactively, from the central stage.

The rules for composition are forbiddingly complex, prescribing not only verse-form and vocal melody but also a complicated spatial arrangement in which the word order within individual verses must be shuffled while maintaining rhyme. And all this while simultaneously responding cleverly to one’s competitors! Making a Sardinian mutetu, referred to as a cantada when it is sung, is truly a tour de force of oral poetic composition, usually requiring many years of listening and practicing. It emphatically puts the lie to the common ideologically based conviction that complexity in poetic composition must always involve writing.

The foremost improviser or cantadori, as poets call themselves, in the southern Sardinian (Campidano) tradition of contest poetry is forty-two–year-old Paolu Flavio Zedda. His case is remarkable, and remarkably instructive for inquiries into inter-agora activities. For he is not only a respected and articulate citizen of the oAgora, highly skilled and widely admired for his performances in the oral marketplace, but also—and equally—a fully participating citizen in excellent standing in the tAgora.

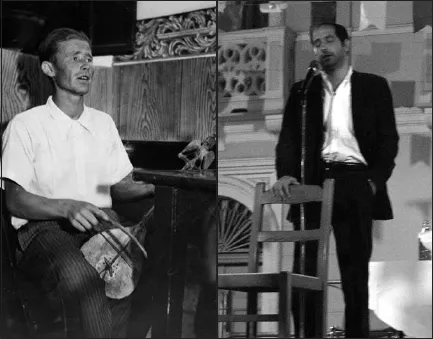

(Left panel) Nikola Vujnovi

playing the

gusle. Permission from David Elmer, associate curator of the Milman Parry Collection, Harvard University.

(Right panel) Paolu Zedda performing in Sardinia, 2007. Photograph by the author.

And in what way, you might ask, does he keep a foot in each of these two worlds? Well, Zedda is a faculty member teaching ethnomusicology at the Università di Cagliari, with a focus on Sardinian oral traditions. And if that weren’t enough, he is also a practicing orthodontist with a substantial clientele in the Cagliari area. In other words, he isn’t only a leading oral poet in high demand (which would itself be quite an achievement) or a professor (again, a creditable position) or a dentist who specializes in straightening teeth (which of course requires advanced training). He is all three at once.

With his dual perspective of oral poet and trained academic/health care professional, and with his firsthand experience in both the oAgora and tAgora, Paolu Zedda is uniquely qualified to explain the oral tradition of mutetu longu.3

Accuracy

A tricky concept, accuracy. And very often a code word summoned to praise tAgora activities while denigrating transactions in the oAgora and eAgora. We’re told that oral traditions can’t preserve history accurately, for example, or that the web is far too subject to change or multiplicity to be a really dependable medium. We’re asked to subscribe to (literally, to “underwrite”) the credo that text is the only possible vehicle for safely and faithfully conveying the immutable data we need to run our cultures. Beware the oral and the virtual; fidelity lies solely in the brick-and-mortar. Or so goes the widespread and enduring myth of Textual Accuracy.

Five propositions

To refute this heavily biased and crippling belief, and to restore an appreciation of each agora on its own terms, I offer five propositions designed to recall the civic responsibility of achieving and maintaining citizenship in multiple agoras (Citizenship in Multiple Agoras). Each of these propositions emphasizes the importance of understanding diversity among media, technologies, and verbal marketplaces. As a group they are intended to approach the common problem of “tAgora default”—and the agoraphobia (Agoraphobia) it engenders—from different perspectives. They’re all getting at the same inconvenient truth, in other words.

1. Accuracy is as accuracy does. This proverbial-sounding observation (Proverbs) is a “literal” reaffirmation of communicative democracy. To paraphrase, only if our ideal of fidelity to truth meets the requirements of the particular agora in which we find ourselves can it have any meaning. Otherwise, it remains a foreign and unintelligible term (even if we suppose ourselves fluent, we’re simply imposing an irrelevant and distorting frame of reference).

2. Accuracy is in the eye of the beholder. This proposition emphasizes the myopia induced by parochial, ideologically driven tAgora prejudice (Ideology of the Text). In conceiving of the very idea of “being accurate,” we unconsciously attune the concept solely to transactions that take place within the tAgora (Arena of the Text), subordinating everything to the rule and model of text. But tAgora accuracy doesn’t fit the oAgora or eAgora.

3. Accuracy is usually, and wrongly, understood as [textual] accuracy. Though we don’t pause to consider the distortion, by accuracy we conventionally mean accuracy as applied to texts, as literal truth, as indisputable fact (Just the Facts). As a post-Gutenberg culture, as people of the book, we always and everywhere include the bracketed adjective as an indispensable part of the definition, subscribing ideologically to [textual] accuracy.

4. Accuracy is “marked” by its covert reference to textuality and the tAgora. Accuracy already means tAccuracy (Texts and Intertextuality). The proof of this hidden agenda lies in the preordained focus of the term. Consider how parochially we use the word: in order to describe or even imagine other kinds of accuracy, we have to undo the presumption (Reading Backwards), remove the default. We have to add qualifiers to the monolithic concept in order to deflect its inherent thrust. To designate anything else we need an intervention—as in oAgora accuracy, or eAgora accuracy. We might compare the situation to the coining of “oral literature” as a term designed to overcome the inherent tAgora bias of “literature,” marked for letters and texts. It’s only too easy to see where the cultural conventions lie, and how hard we have to labor to get beyond them.

5. At root, accuracy simply means “taking care of.” It may come as a surprise, but there is nothing fundamental in the term itself that mandates textual definition. The English word derives from Latin accuratus, with the meaning “taken care of, exact.”4 And who’s to say that we can’t take care of our verbal business with great precision in the oAgora and eAgora as well—as long as we construe accuracy within their own frames of reference? True enough, sentencing either OT (oral tradition) or IT (Internet technology) to unnatural confinement in the tAgora causes nothing but problems, inducing agoraphobia at every turn. Who can aspire to be accurate when speaking in an unintelligible foreign tongue?

But we can do better than that. Let’s attempt to understand accuracy within the individual agora, according to the applicable rules.

Rethinking accuracy

One of the primary tenets of the Pathways Project is that experience, perception, and communication are always and everywhere filtered by the media and technologies we use. It’s not a question of whether this self-evident proposition is true, but simply how it works out in the case of each medium and technology.

But cognitive habits are hard to break, or even consciously recognize. We are so fluent in tAgora communication that we don’t stop to assess its influence on how we interrelate and transfer knowledge, art, and ideas; without further thought, we take textuality and its arena as the common denominator, the standard, the bedrock. Of course, that working assumption is patently wrong: to map living, multidimensional experience onto a printed page raises as many problems as it putatively solves. Most museums only remember reality (Museum of Verbal Art). They can’t ever contain it.

Fundamentally, there is no such thing as a one-for-one, mimetic portrayal of reality in any medium, never mind transferal of that experience to another person. Reality can only be sampled, hinted at, and then always in fragmented and reduced form (Reality Remains in Play). The overpowering ideology of text—ultimately a deal with the devil—has bewitched us into accepting the tAgora credo that texts can capture and contain reality, but nothing could be further from the truth. It is never a matter of freezing knowledge, art, and ideas for later consumption. It is always a matter of choosing which medium or technology we wish to use and fully appreciating its built-in liabilities as well as its endemic advantages. And there are always both kinds of features to consider.

In regard to media, then, there are no perfect and complete—no universally accurate—representations. There is only a selection of lenses, each of which offers a particular kind of accuracy, an idiosyncratic take on reality. From this principle it follows that a lack of [textual] accuracy in the oAgora or eAgora should not necessarily be interpreted as an error or shortcoming, but, at least potentially, as its own, agora-specific brand of accuracy.

What is oAccuracy?

If you’re looking for absolute stasis—cold, hard fact that refuses to adjust as the environment around it morphs—don’t bother searching the oAgora. Such immutable, inflexible items are in short supply. And why? Because they serve no useful purpose in a constantly morphing agora. To put it most plainly, all they can accomplish is to inhibit the natural dynamics of navigating through networks of potentials. Accuracy in this marketplace doesn’t have anything to do with the brittleness of verbatim repetition (Recur Not Repeat). oAccuracy means fidelity to the system, not the thing (Systems versus Things).

When a South Slavic bajalica, or conjurer, diagnoses her patient’s malady and adjusts her healing charm to fit the disease, she is oAccurate. When an African society responds to the advent of a new king by systematically “forgetting” one person in the royal lineage, thus keeping the official cultural history of kingship at the authoritative seven individuals, they are cultivating oAccuracy. When Basque bertsolaris fashion never-before-uttered verses that respond competitively to their opponents’ verses and will never be uttered again, everyone involved is behaving oAccurately. When a Rajasthani epic bard narrates what we textualists would consider only a “part” of the overall story-cycle, leaving the whole implied (but in the oAgora very much present to the communicative ...