![]()

PART ONE

TRANSPERSONAL PSYCHOLOGY

![]()

ONE

PARTICIPATORY SPIRITUALITY AND TRANSPERSONAL THEORY

My contribution to the participatory turn in transpersonal studies was formalized in 2002, when Revisioning Transpersonal Theory (Revisioning hereafter) was published shortly after R. Tarnas’s (2001) preview of the book. The book had two general goals: (1) to critically examine some central ontological and epistemological assumptions of transpersonal studies, and (2) to introduce a participatory alternative to the neo-perennialism dominating the field thus far. At that time, R. Tarnas (1991) had already laid the foundations of a spiritually informed participatory epistemology, Kremer (1994) had developed a participatory approach to Indigenous spirituality, and Heron (1992, 1996, 1998) had introduced a participatory inquiry method as a relational form of spiritual practice and articulated a participatory ontology and epistemology. Nonetheless, the prevalent transpersonal models conceptualized spirituality in terms of replicable inner experiences amenable to be assessed or ranked according to purportedly universal developmental or ontological schemes.

Revisioning reframed transpersonal phenomena as pluralistic participatory events that can occur in multiple loci (e.g., an individual, a relationship, or a collective) and whose epistemic value emerges—not from any preestablished hierarchy of spiritual insights—but from the events’ emancipatory and transformative power on self, community, and world. On a scholarly level, I sought to bridge transpersonal discourse with relevant developments in religious studies (e.g., in comparative mysticism or the interreligious dialogue), as well as with a number of modern trends in the philosophy of mind and the cognitive sciences, such as Sellars’s (1963) critique of a pregiven world entirely independent from human cognition and Varela, Thompson, and Rosch’s (1991) enactive paradigm of cognition.

In the wake of increasing interest from other scholars in the participatory perspective, I subsequently explored the implications of the participatory turn for such areas as transpersonal science and research programs (see chapter 2), embodied spirituality (see chapter 3), integral transformative practice (see chapter 4), integral education (see chapters 5 and 6), contemplative education and spiritual inquiry (see chapter 7), consciousness research and integral theory (see chapters 8 and 9), religious pluralism and the future of religion (see chapter 10), and contemporary religious studies (Ferrer & Sherman, 2008a), among others. Most of these developments are included in this book.

More than a decade after the publication of Revisioning, the main aim of this chapter is to assess the current status and ongoing impact of the participatory turn in transpersonal studies. Although ample reference is made to the work of many other participatory thinkers, the analysis focuses on the impact of my work. After an outline of the participatory approach to transpersonal and spiritual phenomena, I identify three ways it has been received in transpersonal scholarship: as disciplinary model, theoretical orientation, and paradigmatic epoch. Then I examine the influence of the participatory turn in transpersonal and related disciplines, respond to several criticisms of my work, and conclude by reflecting on the nature and future of the participatory movement. My hope is that this chapter provides not only an introduction to participatory transpersonalism, but also a collection of scholarly resources for those interested in exploring or pursuing a participatory orientation in transpersonal scholarship.

AN OUTLINE OF PARTICIPATORY SPIRITUALITY

Developed over time (e.g., Ferrer, 1998a, 1998b, 2000a, 2000b, 2001), published as a book (Ferrer, 2002), and expanded in an anthology (Ferrer & Sherman, 2008a; Ferrer, 2008), the participatory approach holds that human spirituality essentially emerges from human cocreative participation in an undetermined mystery or generative power of life, the cosmos, or reality. More specifically, I argue that spiritual participatory events can engage the entire range of human epistemic faculties (e.g., rational, imaginal, somatic, vital, aesthetic) with both the creative unfolding of the mystery and the possible agency of subtle entities or energies in the enactment—or “bringing forth”—of ontologically rich religious worlds. In other words, the participatory approach presents an enactive understanding of the sacred that conceives spiritual phenomena, experiences, and insights as cocreated events. By locating the emergence of spiritual knowing at the interface of human multidimensional cognition, cultural context, subtle worlds, and the deep generativity of life or the cosmos, this account avoids both the secular post/modernist reduction of religion to cultural-linguistic artifact and, as discussed below, the religionist dogmatic privileging of a single tradition as superior or paradigmatic.

The rest of this section introduces eight distinctive features of the participatory approach—spiritual cocreation, creative spirituality, spiritual individuation, participatory pluralism, relaxed spiritual universalism, participatory epistemology, the integral bodhisattva vow, and participatory spiritual practice—which other chapters in this book discuss in greater detail.

Dimensions of Spiritual Cocreation

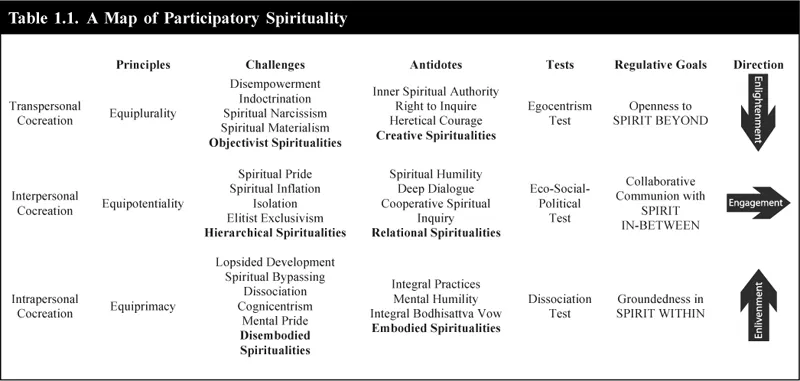

Spiritual cocreation has three interrelated dimensions—intrapersonal, interpersonal, and transpersonal. These dimensions respectively establish participatory spirituality as embodied (spirit within), relational (spirit in-between), and enactive (spirit beyond), discussed below (see Table 1.1, page 12).

Intrapersonal cocreation consists of the collaborative participation of all human attributes—body, vital energy, heart, mind, and consciousness—in the enactment of spiritual phenomena. This dimension is grounded in the equiprimacy principle, according to which no human attribute is intrinsically superior or more evolved than any other. As Romero and Albareda (2001) pointed out, the cognicentric (i.e., mind-centered) character of Western culture hinders the maturation of nonmental attributes, making it normally necessary to engage in intentional practices to bring these attributes up to the same developmental level the mind achieves through mainstream education (see chapters 4 and 5). In principle, however, all human attributes can participate as equal partners in the creative unfolding of the spiritual path, are equally capable of sharing freely in the life of the mystery here on Earth, and can also be equally alienated from it. The main challenges to intrapersonal cocreation are cognicentrism, lopsided development, mental pride, and disembodied attitudes to spiritual growth. Possible antidotes to those challenges are the integral bodhisattva vow (see below and chapter 3), integral practices (see chapter 4), the cultivation of mental humility (see chapter 5), and embodied approaches to spiritual growth (see chapters 3 and 7). Intrapersonal cocreation affirms the importance of being rooted in spirit within (i.e., the immanent dimension of the mystery) and renders participatory spirituality essentially embodied (cf. Heron, 2006, 2007; Lanzetta, 2008; Washburn, 2003a).

Interpersonal cocreation emerges from cooperative relationships among human beings growing as peers in the spirit of solidarity, mutual respect, and constructive confrontation (see chapter 4; Heron, 1998, 2006). It is grounded in the equipotentiality principle, according to which “we are all teachers and students” insofar as we are superior and inferior to others in different regards (Bauwens, 2007; Ferrer, Albareda, & Romero, 2004). This principle does not entail that there is no value in working with spiritual teachers or mentors; it simply means that human beings cannot be ranked in their totality or according to a single developmental criterion, such as brainpower, emotional intelligence, or contemplative realization. Although peer-to-peer human relationships are vital for spiritual growth, interpersonal cocreation can include contact with perceived nonhuman intelligences, such as subtle entities, natural powers, or archetypal forces that might be embedded in psyche, nature, or the cosmos (e.g., Heron, 1998, 2006; Jung, 2009; Rachel, 2013; R. Tarnas, 2006). The main challenges to interpersonal cocreation are spiritual pride, psychospiritual inflation, circumstantial or self-imposed isolation, and adherence to rigidly hierarchical spiritualities. Antidotes to those challenges include collaborative spiritual practice and inquiry (see chapters 4 and 7), intellectual and spiritual humility (see chapter 5), deep dialogue (see chapter 6), and relational and pluralistic approaches to spiritual growth (see chapter 3). Interpersonal cocreation affirms the importance of communion with spirit in-between (i.e., the situational dimension of the mystery) and makes participatory spirituality intrinsically relational (cf. Heron, 1998, 2006; Heron & Lahood, 2008; Lahood, 2010a, 2010b).

Transpersonal cocreation refers to dynamic interaction between embodied human beings and the mystery in the bringing forth of spiritual insights, practices, states, and worlds (Ferrer, 2002, 2008). This dimension is grounded in the equiplurality principle, according to which there can potentially be multiple spiritual enactions that are nonetheless equally holistic and emancipatory. For example, a fully embodied liberation could be equally achieved through Christian incarnation (Barnhart, 2008) or Yogic integration of purusa (consciousness) and prakriti (nature) (Whicher, 1998); likewise, freedom from self-centeredness at the service of others can be attained through the cultivation of Mahayana Buddhist karuna (compassion) or Christian agape (selfless love) in the context of radically different ontologies (Jennings, 1996). This principle frees participatory spirituality from allegiance to any single spiritual system and paves the way for a genuine, ontologically and pragmatically grounded, spiritual pluralism. The main challenges to transpersonal cocreation are spiritual disempowerment, indoctrination, spiritual narcissism, and adherence to naive objectivist or universalist spiritualities. Antidotes include the development of one’s inner spiritual authority and the affirmation of the right to inquire (Heron, 1998, 2006), heretical courage (Cupitt, 1998; Sells, 1994), and enactive and creative spiritualities (Ferrer, 2002; Ferrer & Sherman, 2008b). Transpersonal cocreation affirms the importance of being open to spirit beyond (i.e., the subtle dimensions of the mystery) and makes participatory spirituality fundamentally inquiry-driven (Heron, 1998, 2001, 2006) and enactive (Ferrer, 2000b, 2002, 2008; Ferrer & Sherman, 2008a).

Although all three dimensions interact in multifaceted ways in the enactment of spiritual events, the creative link between intrapersonal and transpersonal cocreation deserves special mention. Whereas the mind and consciousness arguably serve as a natural bridge to subtle spiritual forms already enacted in history that display more fixed forms and dynamics (e.g., cosmological motifs, archetypal configurations, mystical visions and states), attention to the body and its vital energies may grant greater access to the more generative immanent power of life or the mystery (Ferrer, 2002; Ferrer & Sherman, 2008a). From this approach, it follows, the greater the participation of embodied dimensions in religious inquiry, the more creative one’s spiritual life may become and a larger number of creative spiritual developments may emerge.

A Creative Spirituality

In the infancy of participatory spirituality in the 1990s, spiritual inquiry operated within certain constraints arguably inherited from traditional religion. As Eliade (1959/1989) argued, many established religious practices and rituals are “re-enactive” in their attempt to replicate cosmogonic actions and events. Expanding this account, I have suggested that most religious traditions can be seen as “reproductive” insofar as their practices aim to not only ritually reenact mythical motives, but also replicate the enlightenment of their founder or attain the state of salvation or freedom described in allegedly revealed scriptures (see chapter 3). Although disagreements about the exact nature of such states and the most effective methods to attain them abound in the historical development of religious ideas and practices—naturally leading to rich creative developments within the traditions—spiritual inquiry was regulated (and arguably constrained) by such pregiven unequivocal goals.

Participatory enaction entails a model of spiritual engagement that does not simply reproduce certain tropes according to a given historical a priori, but rather embarks upon the adventure of openness to the novelty and creativity of nature or the mystery (Ferrer, 2002; Ferrer & Sherman, 2008a; Heron, 2001, 2006). Grounded on current moral intuitions and cognitive competences, for instance, participatory spiritual inquiry can not only undertake the critical revision and actualization of prior religious forms, but also the cocreation of novel spiritual understandings, practices, and even expanded states of freedom (see chapters 3 and 9).

Spiritual Individuation

This emphasis in creativity is central to spiritual individuation, that is, the process through which a person gradually develops and embodies her unique spiritual identity and wholeness. Religious traditions tend to promote the homogenization of central features of the inner and outer lives of their practitioners, for example, encouraging them to seek the same spiritual states and liberation, to become like Christ or the Buddha, or to wear the same clothes (in the case of monks). These aspirations may have been historically legitimate, but after the emergence of the modern self (C. Taylor, 1989), our current predicament (at least in the West) arguably calls for an integration of spiritual maturation and psychological individuation that will likely lead to a richer diversity of spiritual expressions (see chapters 9 and 10). In other words, the participatory approach aims at the emergence of a human community formed by spiritually differentiated individuals.

It is important to sharply distinguish between the modern hyperindividualistic mental ego and the participatory selfhood forged in the sacred fire of spiritual individuation. Whereas the disembodied modern self is plagued by alienation, dissociation, and narcissism, a spiritually individuated person has an embodied, integrated, connected, and permeable identity whose high degree of differentiation, far from being isolating, actually allows him or her to enter into a deeply conscious communion with others, nature, and the multidimensional cosmos. A key difference between modern individualism and spiritual individuation is thus the integration of radical relatedness in the later. Similarly, Almaas (1988, 1996) distinguished between the narcissistic ego of modern individualism and an essential personhood or individual soul that integrates autonomy and relatedness; for a discussion of the differences between Almaas’s individual soul and the spiritually individuated participatory self, see Appendix 1.

Participatory Pluralism

The participatory approach embraces a pluralistic vision of spirituality that accepts the formative role of contextual and linguistic factors in religious phenomena, while simultaneously recognizing the importance of nonlinguistic variables (e.g., somatic, imaginal, energetic, subtle, archetypal) in shaping religious experiences and meanings, and affirming the ontological value and creative impact of spiritual worlds.

Participatory pluralism allows the conception of a multiplicity of not only spiritual paths, but also spiritual liberations, worlds, and even ultimates. On the one hand, besides affirming the historical existence of multiple spiritual goals or “salvations” (Ferrer, 2002; Heim, 1995), the increased embodied openness to immanent spiritual life and the spirit-in-between fostered by the participatory approach may naturally engender a number of novel holistic spiritual realizations that cannot be reduced to traditional states of enlightenment or liberation. If human beings were regarded as unique embodiments of the mystery, would it not be plausible to consider that as they spiritually individuate, their spiritual realizations might also be distinct even if potentially overlapping and aligned with each other?

On th...