![]()

2

How Villages were Found

“India means her seven hundred thousand villages.”

– M.K. Gandhi

PERCEPTIONS OF THE Indian rural landscape are commonly filtered through a set of encapsulating terms. The rural is associated with the agrarian and the agrarian with the village, as though to speak of the rural landscape is to speak of village India. Most of India, we are repeatedly told, lives in its villages. This notion has been naturalised over time – reaffirmed by academics and political thinkers, circulated in the popular media and literature.

For a long while, social anthropology (or sociology) in India meant village studies. In the 1930s and ’40s anthropologists at Sriniketan pioneered such writings in Bengal, collecting information about the material conditions of village life. In the post-War years, American anthropologists went around Indian villages, mapping social structure and change. Village societies, they showed, were not isolated entities, but embedded within wider social worlds: the “Little Traditions” within them were intimately tied to the “Greater Traditions” of Indian society. When caste became the central focus of the sociological imagination, studies still remained bounded by the spatial frame of the village, seen as the site where castes seemed to exist and operate.

Historical writings consolidated this synecdoche: the village standing for the rural. When tracking the transition from nomadic to settled society, historians of ancient India showed how, with the coming of iron technology and iron ploughs, intensive cultivation became possible, enlarging the frontiers of settled agriculture. With the production of a surplus, villages came into being and state societies emerged. It was as if the establishment of villages was the telos, the pre-designated end-point towards which the history of ancient India had been moving, with the formation of villages imbuing this teleology with meaning, thus allowing historians to track the stages through which agrarian history had unfolded. Within this frame, dominant till recently, spaces outside the settled agrarian had only transitional significance: they were waiting to disappear, to be eliminated by the march of history, transformed by new technology and advanced forms of surplus production. Once settled agriculture appeared, non-agrarian forms could only survive as traces, vestiges of “earlier” modes, silhouettes in a landscape of outmoded and vanishing pasts.

When looking at agrarian change, historians of medieval India explored how village societies in India were organised, how rights and obligations within villages were defined. Reading the past over the post-colonial decades, historians began critiquing the problematic stereotyping of Indian village society, but without unpacking the category “village” as a spatial unit. They argued that Indian villages were not self-sufficient entities insulated from the world outside, neither stagnant and backward nor internally homogeneous and self-reproducing. Rather, village societies were shown as internally differentiated, tied to the wider world through webs of social and economic relations, transformed continuously by many forces of change. Even this critique, however, served basically to reaffirm the idea that rural India was village India, that rural society was peasant society.

Within the nationalist imagination the village became the locus of tradition and culture, virtue and authenticity. If the city was the site of modernity, commerce, and industry, the village was where the “real” India lived, insulated from the seductions of the modern. For Gandhi, in particular, it was the locus of all creativity and goodness, morality and happiness, innocence and purity, beauty and genius, a place of nature to be protected from the corrupting and evil influence of modernity. It had to be saved from the depredations of the city – cultural, moral, and economic.

How did this category, “village”, come to encapsulate the rural? How did the word acquire the status of a synecdoche and start substituting for the rural? Villages existed earlier, of course, but they had appeared in wet zones – in the riverine plains, in regions of intensive cultivation. There were vast stretches beyond the agrarian frontier where settled agriculture was not pervasive, nor were villages. In the 1870s no more than 40 per cent of the surveyed area of Punjab was cultivated. In many regions it was less than 15 per cent. By the early 1890s, before the great era of canal extension, the agrarian frontier had extended, but about 54 per cent was still uncultivated.

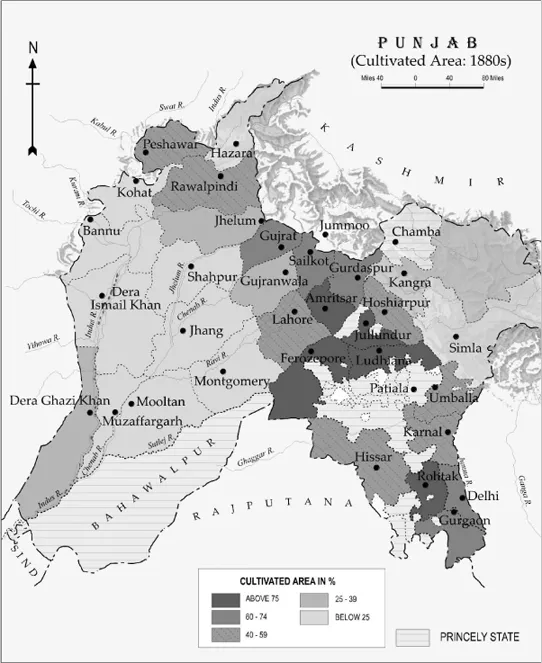

As Fig. 5 shows, the proportion of area under cultivation varied widely over the landscape, as did the forest cover. By the 1870s, the proportion of cultivated area to the total was as high as 80 per cent in the central alluvial plains of Punjab. Within this zone the most fertile tract was the Doab between the Beas and the Sutlej – the Bist Doab, also known as the Jullunder Doab. It was a seemingly continuous plain, unbroken by hill or valley, dotted with clusters of mud-roof houses, sparsely wooded, except near habitation sites and irrigation wells. This zone had a high population density, small peasant farms, and intensively cultivated double-cropped fields – a land of maize and wheat. The proportion of cultivated to total area was equally high in the riverine lands below the River Sutlej – the powadh, as it was called. The powadh of District Ludhiana was covered with intensively cultivated small holdings, producing fine crops of sugar, cotton, and maize. To the north of the Sutlej was the majha tract. The older settled parts of the majha – particularly around Amritsar and Lahore – were highly fertile, amply watered by the Beas and Ravi rivers, and for long the locus of political power in the region.

Fig. 5: The Limits of the Agrarian: Distribution of Cultivated and Uncultivated Land in Punjab, 1891–3. Calculations are based on village papers collated in RAP 1892, 1893.

Beyond these fertile plains of Central Punjab the landscape was radically different. Down in the south-east was a semi-arid and sparsely populated region where dry cultivation coexisted with pastoral farming; here, two crops were difficult to produce, and kharif (the autumn crop) predominated over rabi (the spring crop). To the north-west, beyond the Ravi, was a vast pastoral tract – the bãr – where the nomadism of the upland combined with cultivation in the lowlying riverine belts, the cultivated area in many places being less than 15 per cent. The southern part of the Bari Doab – the land between the Sutlej and the Ravi – was a similar pastoral tract with over 75 per cent of the area around Multan still uncultivated in the early 1890s.

Further west, beyond the bãr, between the rivers Jhelum and Indus, was the Thal, a desert with only small pockets of cultivation and extensive grazing lands, the cultivated area in places being less than 10 per cent of the total. Further to the north-west was a dry submontane tract around Rawalpindi, rocky and bare, the lower heights covered with scrub and the upper zones with Pinus longifolia, with patches of cultivation honeycombed in between, the proportion of cultivated area to the total nowhere more than 40 per cent. On the foothills around Hoshiarpur and Ambala, a tract known as kandi was dry and rocky, as distinct from the sirwal, the long strip bordering Jullunder that was fertile and carefully cultivated. Further up, in the mountain tracts – from Kullu to Kangra – rural life was sustained by an interdependent subsistence economy of pastoralism, terraced cultivation, and the utilisation of forest resources, a region that could produce commercially valuable timber – deodar, teak, sheesham.

Keen to convert all rural spaces into productive landscapes, colonial officials idealised an image of the peasants of central Punjab as a hardy lot busy cultivating their own farms. Settled agriculture was valorised as normative and desirable. When fixed to a piece of land, peasants became knowable and controllable; their lands could be surveyed, assessed, and taxed. Pastoralists were more difficult to control, govern, and extract revenue from. So they had to be settled, fixed to the land, bounded within delimited spaces, and turned into fiscal subjects of the state. Constituting rural spaces as villages was one way of creating such landscapes of settled agriculture. Survey officials went looking for villages everywhere and mapped villages on to the landscape even where there were none. The desired elements of the core agrarian regions were projected onto every variety of space; they provided the frame through which the rural was made intelligible, governable, and taxable.

What happened as a consequence is the conquest of an entire rural universe, a conquest in the strongest sense of the term. To visualise the rural as agrarian, and to imagine the village as the universal sign of the rural, can only be through a process of massive erasure, a refusal to see the legitimacy of other spaces, other habitations – the forests and the scrublands, the pastures and the meadows, the deserts and the dry tracts, the hilly regions and the mountains. To understand these erasures we need to see how villages came to be universalised as a spatial and institutional category, how they were seen, established, and normalised in the colonial period. “Villagisation” here was not a forced settlement of “tribals” and nomads into ordered villages, but a slower and deeper transformation – almost imperceptible – of the entire rural landscape.

How Estate becomes Village

From the earliest days of Company rule, “estate” as a category returns incessantly in all reflections on the Indian agrarian order. It became a category taken for granted, a term that no-one seemed to question. Officials differed on who the proprietor of the soil was, and who was responsible for paying revenue. But they all assumed that “estate” was the term through which the rural was to be ordered. The meaning of the word, however, mutated, changing as Company rule spread north-west from Bengal in the nineteenth century. If we track the history of its mutation, we come to understand how the village was produced as the universal rural.

In the late eighteenth century, when the Permanent Settlement was imposed in Bengal, zamindaris were identified as estates, and zamindars were made liable for the revenue assessed on their estate. The authority and power of the zamindar was both affirmed and subverted. Zamindars could no longer have their own armed regiments or their police force; their judicial prerogatives were restricted and their administration supervised by Company collectorates. They still retained symbolic authority and power, but their “estates” – in the eyes of the Company – were essentially units of revenue administration. Translated into an indigenous term the estate was a mahal, a category that had been in use in revenue parlance since Mughal times. Within the estate could be many hundred villages, each officially anoin...