![]() Part I: Connection versus disconnection

Part I: Connection versus disconnection![]()

1 Capturing territories through energy distribution

The family of territorial technical networks can be divided into three major categories: transportation (road, sea, rail, air); information and communication (telephone and information technology); energy and resources (water and sewage, gas, steam, electricity).1 In the industrial countries of the northern hemisphere the organization of these basic services was gradually structured into large-scale networks and was central to the process of urbanization in the late nineteenth century. These networks became symbols of hygiene and convenience, representing transformed landscapes and lifestyles. Connection, which was a progressive ideal, became the norm. Supported by a group of laws, official documents, texts and ideas – including those of “public service,” “network member” and “assistance policy” – wastewater treatment and energy supply technologies developed their basic forms in this period and have barely changed since. The history of the creation of the major networks is a web in which technical, financial and political choices were entwined. However, this was not without certain ambiguities: it was a battle of technical models, scales, movements and governance modes in which engineers and architects played a key role.

The network-web

The symbolism of the network system is based on a paradox: it simultaneously permits freedom of circulation, while its restraint creates both abundance and dependence. Etymologically, network comes from the Latin nodus or knot. It is the “net” used to capture certain animals in hunting or fishing (see Figure 1).

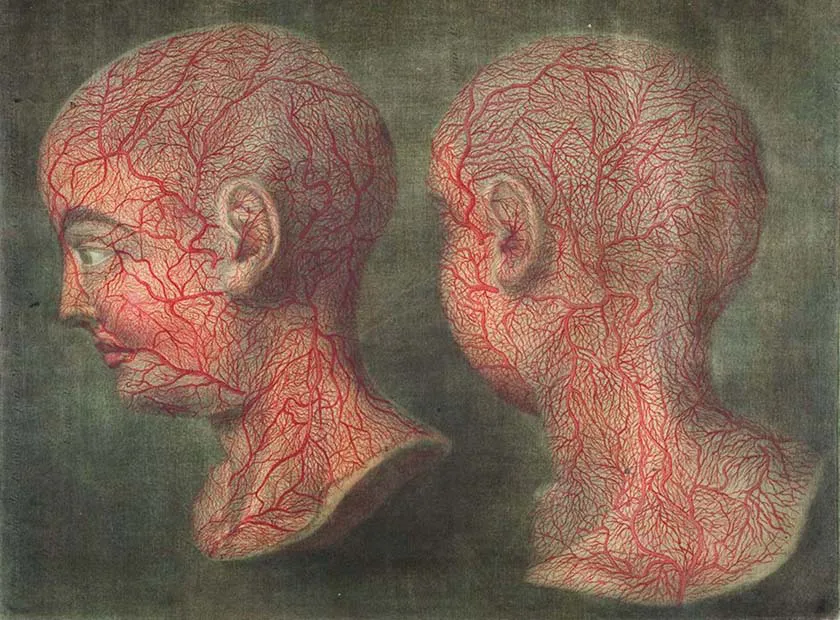

The vocabulary associated with this structure – “link,” “hoop,” “creel,” “ramification,” “web,” “grid” – has always been part of the lexical field of captivity. For a long time, the network described a cluster of fibers, a fabric whose framework was linked to forms in nature. It was subsequently associated with the human body with the discovery of the circulatory system in the seventeenth century (see Figure 2).

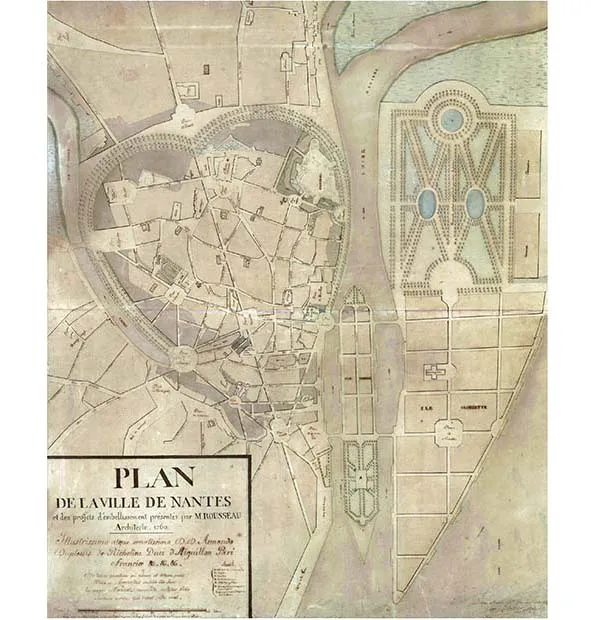

The network materialized as a model that corresponds to the control of natural as well as artificial bodies.2 It was not unusual to see these principles transposed from the human body to the urban landscape in an attempt to solve circulation problems. For example, in 1760 Pierre Rousseau proposed organizing the city of Nantes around a heart-shaped boulevard (see Figure 3).

Figure 1 Net for the capture of animals (1812)

Figure 2 Jacques Gautier d’Agoty, “Superficial Blood Vessels of the Head and Neck” (1746)

Figure 3 Pierre Rousseau, map of the city of Nantes (1760)

The analogy between the urban body and the human body tested the new rationality systems based on the circulation of flows. For the physician or the engineer, the networks distributed and ordered these flows. However, it was also a metaphorical figure that could be applied to politics and power relationships. Plato used weaving as a model for government: the king was a weaver who interlaced and crossed the threads of power.3 The image of the network was subsequently more broadly used to designate a group of people or an organization, connected in order to act together.

It was not until the eighteenth century, however, with the advent of engineering sciences and the creation of a more autonomous discourse on technical domains, that the modern idea of the network emerged. Claude Henri de Saint-Simon, the philosopher of networks, conceptualized his “industrial system” based on his definition of the network organism, which used an analogy between the human body and the social body. Saint-Simon’s approach “consisted in tracing on the body of France, that is, on its territory, networks to ensure the circulation of all of society’s flows.”4 Barthélemy Prosper Enfantin, Saint-Simon’s disciple and the creator of L’Union pour les chemins de fer de Paris in Lyon in 1845, and pioneer of the Suez Canal, stated: “We have enlaced the Globe with our railroads, gold, silver, electricity! – Spread, propagate by these new paths whose creators and masters you are in part, the spirit of God, the education of the human race.”5 Progress made it possible to see the network as a technical, economic and social system; it was the symbol of communion and universal association. Its gradual expansion can be read as an undertaking of territorial pacification and conquest: the network simultaneously frees and subjugates the spaces conquered by its ramifications. Scientific progress and the Industrial Revolution opened a new imaginary field of technology and the technical utopia led to social utopia.6 In the mid-nineteenth century, the creation of urban service networks and the systemization of connections in urban territories were part of this dimension. The ambivalent notion of the network served both to connect, circulate and to mark out control. The railroad, the road network and the hydraulic system became reticular tools that channeled progress and freed men from the obscurantism of the past. The network was the technical and symbolic matrix of modernity; but its wired image of a conquering ascendancy did not fade.

The perception of the network as an ensemble that could imprison people and hinder their freedom would be accentuated in the twentieth century. Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari used weaving as a paradigm of the “royal science,” that is, the art of governing people and using the machinery of state.7 The authors strengthened the metaphor: the image of the link or web corresponds to that of “territorialization,” which is the process of covering and infiltrating a territory through an alienation or a dependence. Deleuze and Guattari established the existence of two types of space: the “smooth,” which has no obstacles, and the “striated,” which is a marked-out space organized to allow the fixing and control processes function. The space is striated, they wrote, “through power, through energy, military-industrial, multinational complexities.”8 Deleuze and Guattari used a network-web rhetoric:

The state needs to subordinate hydraulic power to conduits, pipes, banks that prevent turbulence, that make movement go from one specific point to another, make the space itself striated and measured, make the fluid depend on the solid, make flows follow parallel laminar sections. The state remains involved, wherever it can, in capturing flows of all kinds.9

If the energy network can be perceived as a territorialization, the terms “flows,” “conduits” or “pipes” do not specifically refer to energy for the authors: these pipes and conduits describe power in general; they have a universal value.

From the net to the creel, the network simultaneously supplies and hems in. There is a type of semantic displacement happening here: the network, usually defined by the freedom of circulation and urban solidarity, can be connected to the vocabulary of captivity and the universe of the constraint. It becomes obligation, bondage, fixedness, blockage. These linguistic variations shed further light on a different history of resource distribution and management: conquest.

Conquering and controlling flows

The natural hydrographic network existed before the city, and since time immemorial the brilliance of irrigation systems, from qanats to aqueducts, has demonstrated a subordination of architecture and urbanism to these technical systems. The water network is the oldest. The study of ancient management procedures first raises the question of control and taxation, which is not the prerogative of our modern societies. In the earliest civilizations, there was often a master of water and “it was around and in regard to hydraulic problems that the concepts of social stratifications and political hierarchy emerged.”10 Whoever controlled water structured the organization of communities, thus it was at the moment that there was a centralizing state that the monopolistic administration of resources was organized. Karl Marx and Karl August Wittfogel showed that the rules of water distribution were among the first manifestations and prerequisites of the power of Eastern despotism in so-called pre-capitalist civilizations.11 Wittfogel delved deeper into the study of the “Asian production method” showing that these ancient empires, notably China and Egypt, were founded on total control of water. With the creation of a broad centralized bureaucracy, these “hydraulic societies” or “hydraulic civilizations” controlled the rivers, the irrigation system and agriculture. This emergence of a state that managed resources using monopolistic methods corroborated Pierre Clastres’s thesis, according to which political power preceded and founded economic exploitation.12 The state would create the basis of interdependence and its duration through public management of water and seeds.

The question of taxes affected all of the large ancient cities. In the Roman Empire, the connection to the aqueduct and sewer system was a distinctive sign of the economic power of the owners, who had to pay a tax for cleaning and repairs. Vitruvius stressed the user’s fiscal duties to the state for home economics management.13 Any undertaking concerning planning and developing the water and sewer networks had to be supported by a general consensus or imposed by a sufficiently influential government. Moreover, the fall of the empires brought about the fall of these networks. Only the infrastructure remains, like the Pont du Gard, whose original aqueduct structure function has disappeared.14

Though there were large-scale water systems that structured the organization of vast empires, most territories’ management method was self-sufficiency and the self-management of resources. Before the eighteenth century, water provision depended on local sources and an individual collection system in rivers, wells or public fountains. The medievalist Jacques Heers traced, in Italian villages like Bologna, the process that went from the old multicellular ...