![]()

CHAPTER 1

PLANNING, POWERS AND FUNDING

Without the railway, Aberystwyth would have been a typical Welsh westcoast market town with a small harbour. Even on modern roads with modern vehicles, the 75 miles to Shrewsbury or Swansea will take the better part of two hours to cover. The opening of the Aberystwyth & Welsh Coast Railway in 1864 brought access to markets that were not dependent on droving or the tides. It also brought tourists, and its existence must have contributed to the decision to found the University College Wales there in 1872.

Located where the confluence of the Ystwyth and Rheidol rivers encouraged the development of the harbour, evidence of human activity dating to the Mesolithic and the bronze and iron ages has been found in the area. Edward I’s castle, built in 1277, was attacked by Parliamentarian troops in 1649, its ruins a local landmark. Development of the modern town followed the Local Government Act of 1887, which gave power to the electorate while removing it from landowners. Significant developments, the steam laundry, electric lighting, the pavilion and the Constitution Hill cliff lift, were the work of the Aberystwyth Improvement Company, an investment vehicle for the then Duke of Edinburgh, later the Duke of Saxe Coburg.

The railway takes its name from the Afon Rheidol, the larger of the two rivers. It rises on Plynlimon, the highest point in mid-Wales, some 19 miles to the north-east of the town, flowing southwards to Ponterwyd before narrowing into a ravine as it veers to the south-west and then westwards to join the Mynach at Pontarfynach, the bridge over the Mynach. The earliest reference to the Devil’s Bridge appellation dates to 1734 and there is more than one legend to explain it.

Travellers to and from Aberystwyth were aware of the location’s scenic attractions as it lay on the Llangurig to Aberystwyth turnpike. Never a village, nor even a hamlet, the only significant buildings were the Hafod estate’s hunting lodge, the Hafod Arms Hotel since the 1820s, and the tollgate. There was only a small, scattered, community.

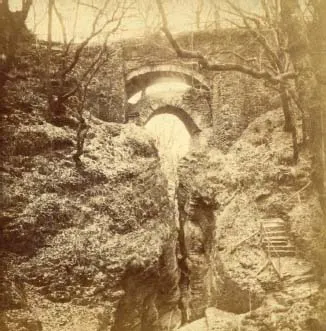

Two bridges crossing the Mynach gorge, one above the other, and a 300ft waterfall attracted tourists to the area, chief among them the artist J.M.W. Turner, in 1795, and the poet William Wordsworth, who was inspired to compose a sonnet about the experience in 1824.

The origins of the oldest bridge are unknown; it might have been built by the monks at the nearby Strata Florida abbey in the eleventh century. The second bridge was built in 1753 and iron railings were added in 1814. The former Cardiganshire County Council built the third to improve the road in 1901 and the original contractors strengthened it 70 years later. The bridges were listed in 1964.

In one sense the council’s efforts were too late, because the turnpike had been diverted through Ponterwyd to Llanbadarn in the 1830s, the present A44, saving two miles, reducing the area’s significance; the Devil’s Bridge tollgate closed in 1845. However, the Cwm Rheidol lead mine, the largest and most productive in the area, and the needs of the Hafod estate, the principal landowner in the region, continued to give the area a purpose.

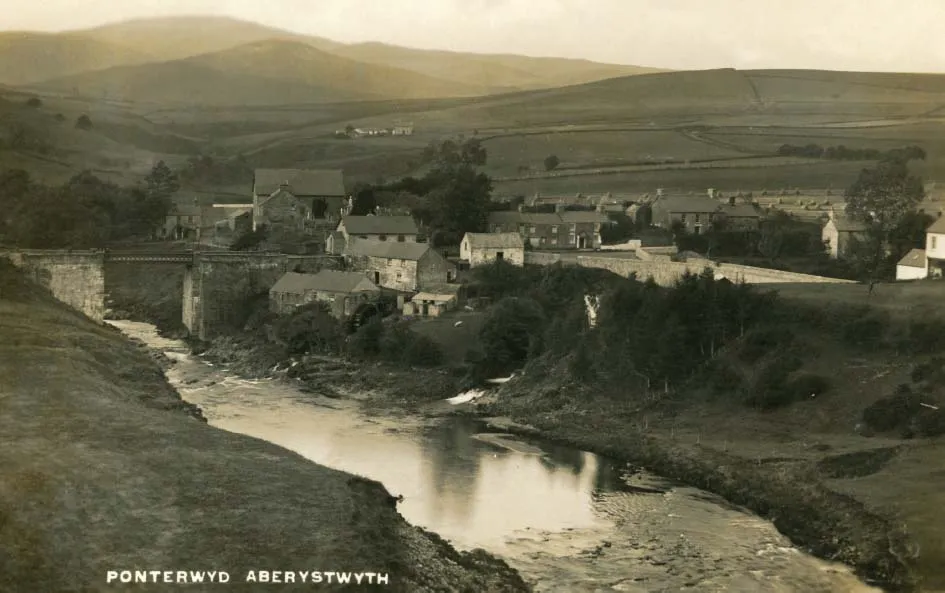

Industry in the Rheidol valley, the mill at Ponterwyd, with Plynlimon in the distance. Since replaced, the bridge carries the main A44 road from Llangurig to Aberystwyth.

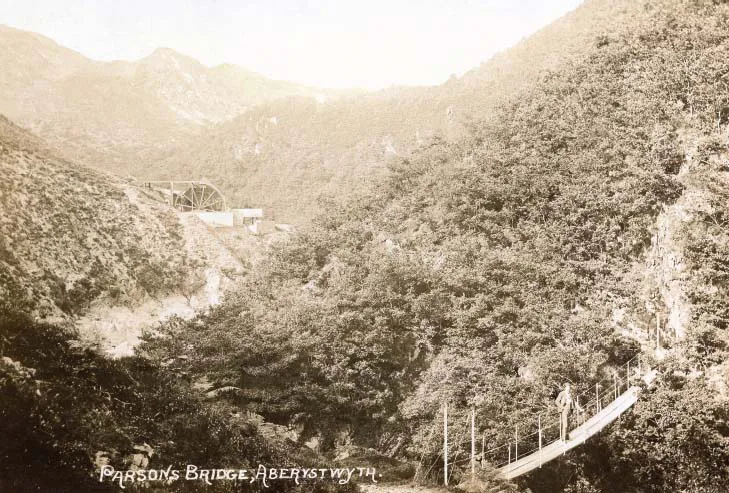

Parson’s Bridge, just over a mile upstream of Devil’s Bridge, was another popular attraction for the 19th/early 20th century tourist. The Temple mine’s 40ft waterwheel provided power for a crusher.

The bridges as they were when consideration was first given to promoting a railway to Devil’s Bridge, before Cardiganshire County Council’s road bridge was built in 1901. (Gyde’s Photo Views)

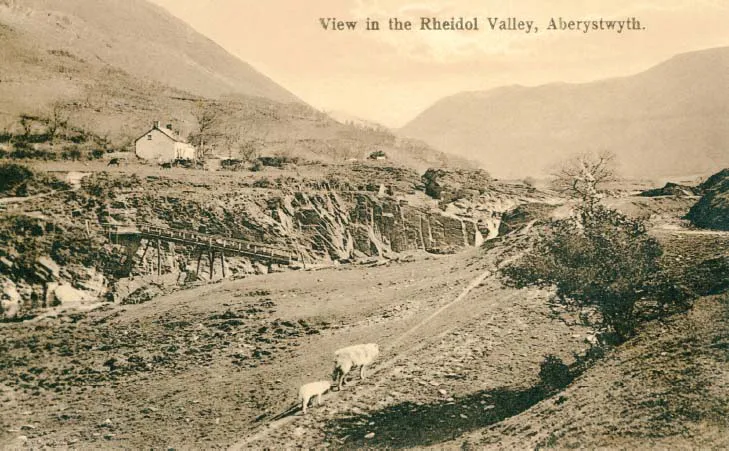

Looking downstream from Rheidol Falls, with the famous stag created by the spoil from the Gellireirin lead mine on the opposite side of the valley. (Wrench)

With the Mynach falling through a 300ft waterfall to meet the Rheidol about ten miles from the coast, the valley opens out into good agricultural land, predominately grazing for sheep and cattle, the river meandering through a sparsely inhabited hinterland as it heads westwards. The upper valley is littered with defunct mine workings, lead, zinc and copper amongst them, but, unlike many similar locations in Wales, no slate. Two-and-a-half miles downstream from Devil’s Bridge, another, less substantial, waterfall lowers the level again, at the appropriately named Rheidol Falls. One landmark, visible for well over one hundred years, is the so-called Rheidol stag, the scar left by spoil dumped from mines at Gellireirin.

Twentieth century additions to the landscape are the Rheidol hydro-electric power station, opened in 1964 and the largest hydro station in Wales, and the planting of many of the upper slopes with conifers.

By the standards of the day, Aberystwyth was a boom town, with developments moving on apace. In 1855 The Welshman described it as a ‘celebrated watering place … filled with distinguished visitors.’ Funds were being raised for the town clock and a daily omnibus conveyed visitors to the celebrated Devil’s Bridge.

A closer view of the miners’ bridge across the river downstream of Rheidol Falls.

The Woodlands Bungalow was one of the catering establishments provided for tourists at Devil’s Bridge. The building still exists, providing for users of a campsite. (Maglona Series)

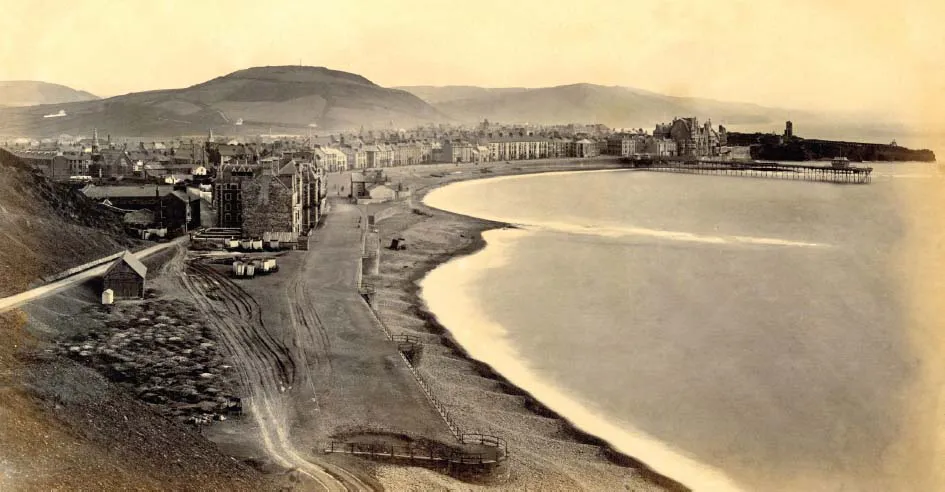

Development of Aberystwyth’s Victoria Terrace was incomplete when this view of the town was taken. The ornate building at the far end of the promenade was built for the contractor Thomas Savin as a hotel but was incomplete when he entered bankruptcy in 1866 and sold to the University College of Wales at a considerable loss.

The first schemes to take a railway to or near Devil’s Bridge were ancillary to proposals to create a through route between the North-West of England and the South-West of Wales. Both the North & South Wales Railway, which deposited a Bill for a railway between Llanidloes and Lampeter in 1853, and the Manchester & Milford Railway, which obtained an Act for its route between the Carmarthen & Cardigan Railway at Pencader and the Llanidloes & Newtown Railway at Llanidloes in 1860, would have passed through the Rheidol valley between Devil’s Bridge and Ponterwyd.

The Manchester & Milford Railway then obtained powers for a branch to Aberystwyth from Devil’s Bridge in 1861, which was abandoned within two years, and went on to obtain powers for a branch to Devil’s Bridge from Crosswood in 1873. This scheme had replaced the independent Devil’s Bridge Railway scheme on the same alignment, which had failed during the parliamentary process the year before; everything was perfect, reported the Cambrian News on 19 January 1872, until the deposit was due to be paid; only two of the six directors attended a meeting to approve its payment and they received notice that three of their colleagues had resigned.

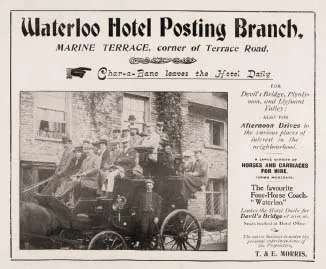

An advertisement for the Waterloo Hotel’s ‘posting branch’, which offered a daily service to Devil’s Bridge. Thomas Morris, the hotel’s owner and coach operator, died on 12 November 1909, aged 79. The Welsh Gazette’s obituary of him gave an insight into Aberystwyth’s transport links before the railways arrived, explaining that he had run a coach between Aberystwyth and Carmarthen until the Manchester & Milford Railway had opened, between Aberystwyth and Llanidloes until the Cambrian Railways connected those places, and then to Devil’s Bridge until the railway opened, when he sold his charabancs. The hotel was demolished a few years ago.

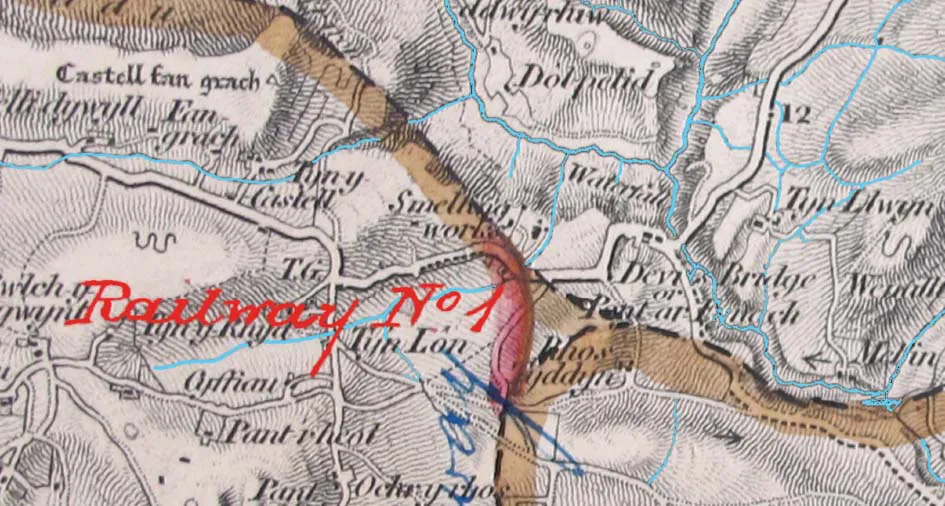

An extract from the deposited plan for the Manchester & Milford Railway’s proposed Aberystwyth–Devil’s Bridge branch, with its triangular junction near Devil’s Bridge. (Parliamentary Archives)

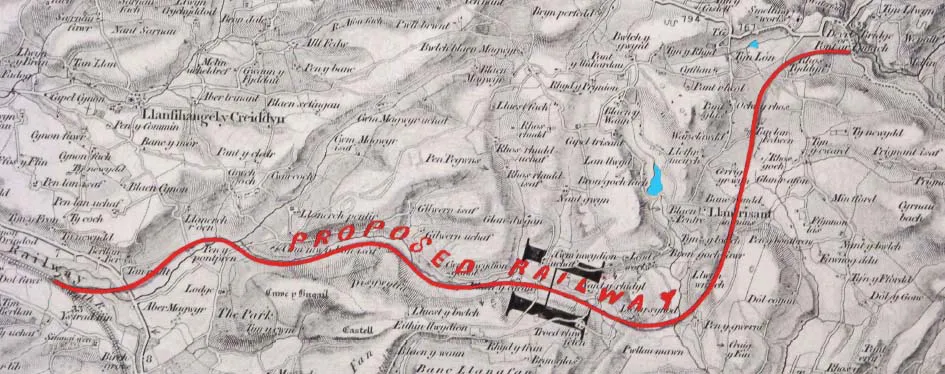

The plan deposited with the independent Devil’s Bridge Railway Bill in 1871. Surveyed by James Weeks Szlumper, the same route was adopted by the Manchester & Milford Railway the following year. Both schemes failed. (Parliamentary Archives)

In 1895 the Aberystwyth Observer (21 November) said that a Captain Bray and others had paid over £100 for a survey to be made ‘a quarter of a century ago’, which must refer to the 1871/2 scheme. Nicholas Bray was a Cornish mining engineer and agent who owned a mine in, and lived in, Goginan.

All these schemes were for standard gauge lines. The engineer for both the 1872 and 1873 schemes was James Weeks Szlumper. In 1876 an extension of time to purchase the land required was obtained but in 1880 it was formally abandoned.

The next development in the advancement of a Devil’s Bridge railway occurred during an auction of property belonging to the Nanteos estate in July 1892. A lot containing several properties in the Rheidol valley, including mineral rights, was one of the few that sold and both the auctioneer and the purchaser, a George Green, appeared to think that there was a likelihood of a railway being built that would benefit the property.

Green was a mining engineer born in Staffordshire who grew up in Manchester, where he received his training. Visiting Aberystwyth to erect a steam engine in the town’s only foundry in 1848, he never left, establishing a business that supplied mining machinery around the world. He was also active in local politics, despite losing more elections than he won. In September 1892 he announced at the mayor’s banquet that there was a movement to build a railway to Devil’s Bridge that he hoped would be done before the start of the 1893 season.

He was soon to be disabused of that notion and it would be another 10 years before the railway was opened to the public. However, there had been some progress towards a railway to Devil’s Bridge. On 19 December 1892, the Evening Express reported being told that J.W. Szlumper had surveyed the route for a narrow gauge line from Aberystwyth through the Rheidol valley earlier in the year. The money required, said the paper, was in place provided the landowners would donate their land.

However, on 3 February 1893, the Cambrian News reported that land negotiations were ‘pending’, adding that landowners were ‘considering the matter in a reasonable way’, implying that they would recognise the public benefit of a railway and be generous when making their land available for it. The question of land value was one that would surface several times before the railway was built, particularly in Aberystwyth. There it was thought that the Cambrian Railways had benefitted unduly by the uplift in land values since land had been bought from the fledgling council for the Aberystwyth & Welsh Coast Railway in the 1860s, not realising that without the railway the land would not have increased in value.

Meeting on 20 June 1893, the town council passed a resolution in support of the railway, debating whether or not to release land at a nominal value or fair rent. One councillor pointed out that if the railway took the land from the harbour and along the river and built an embankment on it, it would save the council the cost of doing so itself. Another did not vote because he felt they had insufficient information about the proposal.

At the next meeting, on 4 July, Green proposed a motion committing the council to releasing land for the railway at a nominal rent but agreed to a proposal to refer it to a committee instead. The Aberystwyth Observer saw this as the final blow to the scheme, forecasting that it would not be revived for ‘many years to come’, saying that the land concerned was ‘absolutely valueless’.

There was no more activity recorded and Green died in March 1895, his vision for a railway up the Rheidol valley unfulfilled. However, a month before his death the Royal Commission on Land in Wales and Monmouthshire, meeting in London, heard evidence in favour of local authorities participating in the promotion of light railways to improve access to rural areas. H. Enfield Taylor of Chester reeled off a long list of places that he thought would benefit, including ‘from Aberystwyth, up the valley of the Rheidol, to the foot of the falls at the Devil’s Bridge, with a lift for passengers and goods to the summit, and a branch to the great district centring on Goginau’. The last is now known as Goginan, and the Ordnance Survey has recorded many disused mines in its vicinity.

This initiative would have been in support of the Light Railways Bill which was enacted on 14 August 1896. Intended to encourage the development of remote areas, the legislation provided for the creation of a commission that would put it into effect. It authorised local authorities and others to apply for powers to build railways, permitted local authorities to make loans to, or invest in, such railways, and allowed the treasury to make advances not exceeding a quarter of the capital.

Light railways would be freed of the requireme...