![]()

ONE

Guiding Principles

Although sexual intercourse is, in essence, a bodily function, individual attitudes and experiences are always shaped by the world in which one lives – by legal constraints, by medical ideas and (in many societies, including medieval Europe) by religious beliefs.

Religious Beliefs

In the tiny parish church of St Botolph’s, Hardham, West Sussex, is a quartet of twelfth-century wall paintings that tell the story of Adam and Eve. In the best preserved, the first man and woman are unashamedly naked. Then Eve succumbs to the Temptation, represented by a strange winged serpent. The other images depict the couple after the Fall, performing agricultural tasks, immersing themselves in water to quell their newly emerged lust, and finally cowering in shame, hiding their nakedness with their arms.1

This familiar Bible story was at the heart of medieval understandings of sex. Before the Fall, Adam and Eve represented human nature as it was meant to be: they were immortal and free from suffering, and their sinless bodies functioned perfectly. After the Fall, everything changed.2 As the early thirteenth-century English treatise Holy Maidenhood put it: ‘If you ask why God created such a thing [as sex], this is my answer: God never created it to be like this, but Adam and Eve perverted it through their sin and corrupted our nature.’3 Such was the importance of this process that the nature of sex in the Garden of Eden was the subject of considerable theological debate. Some authorities argued that prelapsarian people would have reproduced asexually, like angels, but this was very much a minority view.4 Most theologians thought that God designed sexual intercourse as a means of perpetuating the human and animal races, and that He created sexual pleasure as an added incentive to the fulfilment of this goal.5 It was, however, generally agreed that Adam and Eve did not have sex in Paradise, either because there was insufficient time before the Fall, or because God did not order them to do so.6

Nevertheless, medieval people were fascinated by the possibility of prelapsarian sex, and debated what it would have been like. Some argued that it would have been completely free of both sin and pleasure, with the genitals functioning like any other body part; having an erection would have felt no different to moving an arm or leg. Others thought that sex would have been more pleasurable before the Fall, when bodies were both healthier and more sensitive. However, because these perfect people were untroubled by lust, they would have had sex only in order to reproduce, with every act of intercourse producing healthy offspring.7 Related physiological puzzles were also much discussed; it was, for example, deemed unlikely that Eve would have menstruated or that Adam would have experienced wet dreams, since their bodies were perfectly calibrated. Some even suggested that semen would not have existed in Paradise; Hildegard of Bingen (1098–1179) thought that men would instead have produced some sort of ‘pureness’. Others disagreed, reasoning that Adam and Eve could not have obeyed God’s command to ‘be fruitful and multiply’ without it.8

If many aspects of sex before and after the Fall were unknowable, the increased role played by shame was unquestionable. In a postlapsarian world, sex was irrevocably altered: the events that took place in Eden transformed a simple bodily function into something disruptive and uncontrollable. People were embarrassed by their over-sensitive genitals, which were no longer obedient to reason.9 More troublingly, sex became the means by which Original Sin was transmitted: because sex was impossible without lust, children who were conceived through intercourse inevitably received this taint.10

These facts coloured all medieval discussions about sex. St Augustine (354–430), whose writings were widely read throughout the Middle Ages, thought that all sex was sinful, because it inverted the proper hierarchy of mind and body and caused, through orgasm, ‘an almost total extinction of mental alertness’. It thus served as a reminder of, perhaps even a partial re-enactment of, the Original Sin which led to the Fall.11 Such sentiments informed many of the texts that seem to suggest that the medieval Church disapproved, wholeheartedly and without nuance, of any form of sexual activity. For example, according to the Quinque Verba (a fourteenth-century manual for the instruction of priests):

Lust is the seventh deadly sin, and lust means the desire for illicit pleasures in many forms such as fornication, whoring, adultery, debauchery, incest, sacrilege, unnatural vices, and other horrendous sins. Still, it is not a good thing to dwell on these things or speak of them at too great a length, but, rather, to grieve over and fear them.12

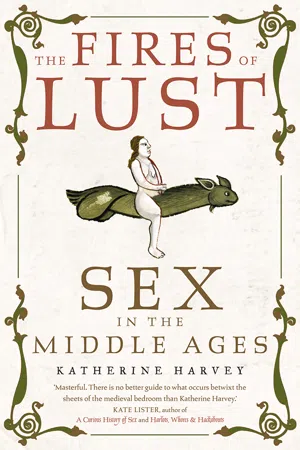

Adam and Eve are tempted by the serpent, in a 12th-century wall painting from St Botolph’s Church, Hardham. The serpent, though now less visible from wear, is depicted giving the apple to Eve.

The reason for such fear was explained by a twelfth-century English sermon which proclaimed that ‘Bodily pleasure is but for a moment; but the fire which follows thereon will endure forever.’13 The surest way to avoid hellfire was to remain a virgin.

According to Holy Maidenhood, which was written to persuade holy women of the benefits of virginity, the best sexual deterrent was meditation on ‘that sinful act through which your mother conceived you – that indecent heat of the flesh, that burning itch of physical desire, that animal union, that shameless coupling, that stinking and wanton deed, full of filthiness’.14 Marriage was, the author claimed, the least meritorious of the three states in which a Christian might honestly live, ‘for marriage brings forth her fruit thirtyfold in heaven, widowhood sixtyfold; maidenhood with a hundredfold outdoes both.’15 Being a virgin placed a woman (or, indeed, a man) on the level of the angels, or perhaps even above them, since it was harder to remain pure on Earth than it was in Heaven.16 Indeed, given that being a true virgin meant avoiding not just sex with a partner, but masturbation and even impure thoughts, it is surprising that any mere mortal achieved it. The scale of the challenge is illustrated by the case of an unfortunate young monk who was persecuted by a demon. Whenever he began to pray, the evil spirit rubbed his genitals until he was polluted by an emission of semen. Although the man was otherwise of good behaviour, Bishop Hildegard of Le Mans (1096–1125) ruled that he was no longer a virgin, since he had participated (however unwillingly) in a ‘shameful act of fornication’.17

Yet despite the clarity of this verdict, and despite Holy Maidenhood’s assertion that virginity was ‘a treasure that, if it be once lost, will never again be found’, many authorities suggested that virginity could be regained. St Augustine believed that the will was central in such cases: if a woman had not experienced desire, then her spiritual virginity was intact, even if her body was not. According to Peter Damian (c. 1007–1072), those who questioned God’s ability to restore virginity (either physical or spiritual) were guilty of questioning His power. If, Damian fumed, God could be born of a virgin, then of course He could achieve the much lesser feat of repairing lost virginity. For pious women who longed for the religious life, but were obliged to marry, such arguments offered the possibility of salvation.18 The Norfolk mystic Margery Kempe (c. 1373– c. 1438), a married mother of fourteen who was tormented by her lost virginity, received the ultimate proof that sex did not have to signal the end of a woman’s spiritual life when she tearfully bewailed her fallen state to Christ (with whom she regularly conversed). He reassured her that because she was ‘a maiden in [her] soul’, she would dance alongside the holy virgins in Heaven.19

Thanks to Adam and Eve, the idea that sex was sinful influenced all medieval lives. Nevertheless, most people opted for marriage over virginity – and unlike Margery Kempe, most do not seem to have felt like failures. Nor should we assume that those who took wedding vows were automatically seen as inferior to those who took vows of celibacy.

Marital sex (if performed correctly) was not seen as a barrier to salvation, and by the later Middle Ages the Church was increasingly willing to acknowledge that it could even be a good thing: it saved the souls of those who were incapable of lifelong abstinence and produced Christian offspring.20 Moreover, as the English friar John Baconthorpe (c. 1290–1347) observed, marriage had wider benefits, for ‘man does not just aim at generating offspring, for the multiplication of the species, like a beast; he aims at living a good and peaceful life with his wife.’21

How far the ordinary Christian absorbed and was influenced by these ideas is largely unknowable, but Fasciculus Morum (an early fourteenth-century English handbook for preachers) reveals the moral messages delivered from the pulpit. Churchgoers were, for example, taught that lechery was offensive to God, and pleasing to the Devil.22 They were also reminded that great care must be taken over even seemingly harmless physical contact and conversations, since lust was like a fire and could be ignited by a spark.23 Such general teachings were supplemented by warnings about specific forms of sexual sin, including fornication – which was a grave sin because it could never be justified (unlike, say, theft in time of need), because it suggested that humans were worse than animals (some of which mated for life), and because it caused social disorder, for ‘if everybody could freely sleep with anyone, frequent struggles would arise, strife, hatred, homicide, and many more evils.’24 The married faithful were also warned against infidelity, and reminded that husbands must not ‘become adulterers with their own wives, using sex not for procreation but for their lustful pleasures alone’.25 Finally, parishioners were taught about incest and sodomy, even though the latter was so repulsive that the author could not bring himself to discuss it, simply writing that ‘I pass it over in horror and leave it to others to describe it.’26

The moral instruction of the medieval Christian also covered chastity, which in this context meant sexual restraint within or without marriage, rather than complete abstinence; it was achieved through a combination of self-control and self-mortification (such as fasting or flagellation). The message was reinforced with purportedly true tales of continence, including one about a man who suffered from bad breath. When he asked his wife why she had not told him, she replied that she ‘thought that all men’s mouths smell that way’. This proved that she was a truly chaste wife, who had never kissed another man.27 Preachers also praised virginity as the ideal state, warning that it could be lost ‘through unchaste touching and hugging’ and reminding their flock that ‘as a sign of his love and reverence of virginity, Christ chose to be a virgin, to be born of a virgin, and to be baptised by a virgin.’ Those who imitated His life of exemplary sexual purity would ‘follow Christ to the Kingdom of Heaven’.28

Such exhortations to emulate Christ were common in medieval Christianity; He, along with the saints, was constantly held up as an example of pious living to be imitated by the faithful. It was in this spirit that Bishop Herbert of Norwich (1090–1119) wrote to Thurstan the monk:

My son, see to it that you maintain your chastity, without which it is impossible to please God. A virgin was Chr...