![]() WORSHIP

WORSHIP

in the

OLD TESTAMENT![]()

CHAPTER 1

WORSHIP: A CONCEPT STUDY IN BIBLICAL HEBREW

Peter Y. Lee

Worship is at the very heart of the Old Testament. There seems very little doubt about this assertion. To be in the presence of the Lord in his house of worship represented one of the highest expressions of the blessed life, if not the highest. The psalmist in Psalm 84:10 describes such contentment that comes from worship when he says, “For a day in your courts is better than a thousand elsewhere. I would rather be a doorkeeper in the house of my God than dwell in the tents of wickedness.” A similar sense of bliss is mentioned in Psalm 27:4: “One thing have I asked of the LORD, that will I seek after: that I may dwell in the house of the LORD all the days of my life, to gaze upon the beauty of the LORD and to inquire in his temple.” These two poetic declarations are samples of countless others in the pages of Scripture that state the genuine joy found in the true, godly worship of God (see Ps. 36:7–9; 47:1–12; Isa. 2:2–3; 44:28; Jer. 3:17–18; Mic. 4:1–3).

In many ways, the entire direction and flow of the history of Israel pivots on this aspect of worship. When Israel was properly worshiping the Lord, all was well. It is when they engaged in improper worship that their life began to collapse. The zeal that the Lord had for his own glory would not permit such impropriety in the worship life of his chosen people (see Exod. 20:3; Isa. 43:25; 48:9–11; 49:3; Ezek. 36:22–23; Ps. 106:7–8; Rom. 9:17). He revealed to them set standards on how worship is to be done, and he would not settle for anything less. Above all else, Israel’s worship was required to be in accordance to his revealed Word.

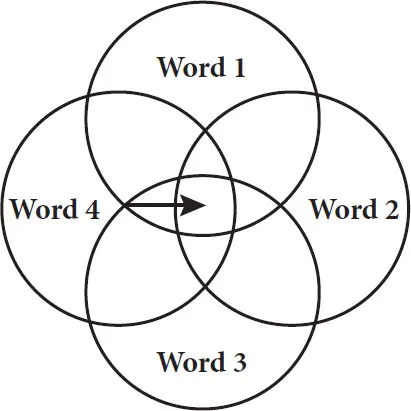

But what was that biblical standard of worship? The intent of this volume is to answer that very question. This opening chapter will introduce key concepts that make up a biblical understanding of worship by examining key words and translational methodologies in Biblical Hebrew. Although there is some semantic overlap, certain words in Biblical Hebrew provide a particular contribution to comprehending the Israelites’ worship life. It is the combination of these words that clarifies the concept of worship in the Old Testament (see diagram). The investigation of these words will reveal what it meant for the people of the Old Testament to participate in proper worship of the Lord. Although such an approach cannot address every detail in the worship life of ancient Israel, it will nonetheless give a framework on which Israel engaged in their devotions to their Sovereign. From this study, we will see the following five principles clarified as we explore the semantic domains that make up a study of worship: (1) sacred journey, (2) sacred structures, (3) sacred practices, (4) sacred disposition, (5) and a sacred goal.

WORSHIP AS CONCEPT IN TRANSLATIONAL PRACTICE

Before our study begins, we begin with two brief comments on methodology. The first is regarding the choice of Hebrew words examined below. There are words in Biblical Hebrew that can be properly translated “worship.” However, there are a number of other words that cannot be translated as such yet are included in this study. The reason for this is because the concept of “worship” is broader than words that can be translated as “worship.” If we were to narrow our research to only those few words that mean “worship,” we would have an extremely limited and unhelpful picture of Israel’s worship life. This is because the domain of words related to worship is larger than the singular usage of words expressly translated from Hebrew to English as “worship.” This would mean such an approach would fail to include analysis or evaluation of the “fear of God” because these three words are not technically translated as “worship” when moving from Hebrew to English, even though the context and meaning of this phrase has great implications for worship, both in the time of the Israelites and today. Failing to study these related words, therefore, will hinder our final goal—which is to gain an accurate concept of worship in the Old Testament.

Second, the words under examination should not be taken as representing concepts. Rather, each word is part of an overall schematic (mosaic) that contributes to a general holistic understanding of worship. Each “word” provides an aspect of understanding worship. It is only when they are systematized that we are offered a “concept” of worship. This distinction has been the battle of lexicographers ever since the publication of James Barr’s seminal work The Semantics of Biblical Language. In it he criticized biblical theologians for “overload[ing] the word with meaning in order to relate it to the ‘inner world of thought.’” By “inner world of thought,” Barr meant the mistaken way in which scholars did conceptual studies in the name of lexicography. His point is that this is not lexicography. The statement “God is love” captures a conceptual idea that cannot be inserted in every occurrence of the word “love” or “God.” Such an approach obscures the meaning of a word in any given context. All of the words studied below have a wide range of meanings, one of which is related to worship. Thus it is the meaning associated with worship that is the focus of our interest. More than a vocabulary lesson, my goal is to gain a clearer understanding of the theme of worship by examining the use of these key words in the literary context of worship. Therefore, we will begin this study to see what lies beneath it to aid in understanding worship in biblical Hebrew.

Sacred Journey

Worship in biblical Israel required that Yahweh’s followers journey to him. There is a connotation that requires their seeking him in the place where he would reveal himself.

The word darash has the general meaning “to seek.” The nuance of the word is often effected by the context and the object of what is sought. In cases where the object being sought is God or objects and/or places associated with God, there is a sense in which the purpose of the seeking is for the sake of worship. Andrew Hill points out two examples where darash is even translated as “worship” in the RSV (Ezra 4:2; 6:21). What this word tells us is that there are certain locations that the Lord himself designates as the only proper places for worship.

Perhaps the best example of this sacred use of darash is in Deuteronomy 12:5. The first four verses describe the Deuteronomic mandate placed on Israel to destroy the foreign pagan worship sites once they have settled in the land of Canaan. In addition to this, verse 5 states that the Lord will choose the place where he is to be worshiped. Israel is to “seek” this place. Regardless of which portion of the land they are allotted as their inheritance (Num. 32; Josh. 13–19), worship will be centralized at one place and the Israelites are to journey to this place for worship. The use of the verb bo (to enter), which immediately follows darash, confirms this expectation to travel to a particular location. This is also reinforced in verse 11, which is nearly identical to verse 5. Where the verb darash and bo are both used in verse 5, only the verb bo is used in verse 11. This suggests that the two different words communicate the same concept of a sacred place.

The word darash occurs prominently in 1 and 2 Chronicles with God as the direct object (1 Chron. 10:14; 13:3; 15:13; 16:11; 21:30; 2 Chron. 1:5; 7:14; 12:14). It frequently occurs in combination with the related verb biqqesh, which also means “to seek” (1 Chron. 16:10, 11; 2 Chron. 11:16; 15:15). Second Chronicles 7:14 is particularly helpful as it affirms that when the people of God suffered the consequences of their covenant violation (i.e., exile), there was still hope of restoration if they only “seek” the Lord with sincerity and humility. In fact, the Chronicler measures the success of the past Judean kings based on whether they “sought” the Lord (2 Chron. 14:4; 15:12) or not (2 Chron. 25:15, 20). The message to the postexilic community who received this book was clear: as difficulties arise in their task to rebuild the ancient cult center in Jerusalem, the Lord would bless those who “seek” him but reject those who do not.

Without a doubt, the notion of “seeking” this central place of worship is behind the rationale for the pilgrim festivals mentioned in Deuteronomy 16:1–17, where the three annual Feasts of Unleavened Bread, Weeks, and Booths are described. Verse 16 states explicitly the necessity of travel and even alludes to Deuteronomy 12: “Three times a year all your males shall appear before the LORD your God at the place that he will choose.” Notice the reference to the “place that he will choose” is similar to Deuteronomy 12:5: “the place that the Lord your God will choose.” Although the verb darash does not occur in chapter 17, the verb bo does, thus reinforcing the necessity to seek the Lord by “going” to this centralized site of worship.

In contrast to this centralization of worship was the practice of the patriarchs. It was not uncommon for them to build altars at various locations where God performed a significant, redemptive act (Gen. 12:7, 8; 13:18; 22:9, 13; 26:25; 33:20; 35:1, 7). Since the patriarchs were sojourners (not residents) in the land of Canaan, they were not required to localize their place of worship. Once their children claimed that land as their covenantal inheritance, however, worship was no longer to be done at numerous locations. Instead, there would be one central place with one central altar that they must “seek.”

This singular place of worship contrasted with the worship of Canaanite deities, which required numerous worship sites. Since Israel was strongly committed to monotheism (Deut. 6:4), this was paralleled with the one site of worship. This was the reason that Joshua panicked when the Transjordanian tribes of Reuben, Gad, and Manasseh built an altar at the frontier of the land of Canaan. It was only after they explained that this was a memorial, not a cultic center, that the remaining tribal groups held off any formal acts of judgment against them (Josh. 22:10–34).

This was also the reason that Jeroboam’s act in 1 Kings 12:25–33 was abominable. In this passage, Jeroboam established not just one illegitimate worship site but two, one in Dan and the other in Bethel. He knew that in order to establish a new northern Israelite nation, his people could not continue to go to Jerusalem to offer worship at the central shrine, where their allegiance to him would be challenged. He needed to establish his own religious practice; thus he constructed the two false places of worship. It was due to this practice that the Lord condemned him and eventually rejected his kingship (1 Kings 13).

Thus in the word darash we read about the call to the ancient Israelites to “seek” their God by journeying to their central cult site, which would eventually be the temple of Solomon in the city of Jerusalem. Worship, therefore, could only be done in one proper place. Anywhere else would be a disgrace.

Sacred Structures

Worship was done at specially designated locations, in specific structures of worship. Prior to the establishment of the temple and thus the required pilgrimage described above, the lone structure of worship was the tabernacle. There were various Hebrew terms used for the tabernacle, each of which highlighted particular aspects of the structure. The most prominent section dedicated to the tabernacle is Exodus 25–31 and 35–40, which gives a detailed description of its architectural design and construction. The first term used in reference to the tabernacle was miqdash (see Exod. 25:8; cf. Lev. 16:33). There had been an increasing anticipation for this structure ever since the redemptive event in Exodus 14–15, where the Lord divided the waters of the Red Sea to provide a way of salvation for his people (Exod. 14). This colossal event was celebrated in song in Exodus 15, which praises the Lord as the Divine Warrior who freed his people so that they may worship him at the mountain of his inheritance in his “sanctuary” (miqdash, v.17). There was thus an expectation for this coming “sanctuary.” It is fulfilled in Exodus 25:8 as the Lord builds this structure through the Israelites at Mount Sinai.

The root of this word is derived from quiddesh, which means “to be holy.” Thus it seems that the holy character of God is accentuated by this term. Although the word miqdash occurs only in Exodus 25:8 within the tabernacle sections of chapters 25–31 and 35–40, the fact that this is the first word used in reference to the tabernacle gives the reader the primary understanding of its intrinsic character. Above all else, it is a holy structure. Its holy characteristic is further emphasized by the fact that the word qodesh, ...