Contradictory Developments – New Fears and Hopes

Since 2014 and the European-wide elections to the European Parliament (the date when I finished writing the first edition of this book), we have experienced vast socio-political changes in our globalized world (some of which were quite unpredictable, others were predictable but not sufficiently acknowledged). Fear and hope – as well as other emotions – have been widely instrumentalized by political parties, in manifestos and speeches, on posters, in debates, interviews, social media and other genres. This is because topics such as migration, climate change, ‘national’ nostalgia for the past and the destabilization of liberal democracies are dominating the public debate in all member states of the European Union (EU) and beyond.

Here, I list just a few – quite contradictory – developments: the Brexit referendum, 23 June 2016; the election of former TV-entertainer, billionaire and demagogue Donald Trump to President of the United States, 8 November 2016; the so-called ‘refugee crisis’ in 2015/16; the establishment of far-right populist governments in Austria on 17 December 2017 (and its abrupt and unforeseen end on 18 May 2019), and in Italy on 28 May 2018 (and its end on 29 August 2019); and the election of the far-right politician Jair Bolsonaro to Brazilian President, on 28 October 2018. On the other hand, in France, the former social democrat Emmanuel Macron, who founded a new party ‘En Marche’ based on a broad social movement cutting across the traditional left and right cleavages, defeated far-right populist candidate Marine Le Pen in a close second round, 7 May 2017, in the election for presidency.1

Since 2014, we have also experienced horrendous terrorist acts such as in Paris (2015) and Nice (2016), Berlin (2015) and Munich (2016), Ankara (2015, 2016), Orlando (2017), Pittsburgh (2018) and Christchurch (2019), as well as Halle (2019) – apart from the almost daily terrorist attacks and on-going (civil) wars in Iraq, Pakistan, Libya, Sudan, Nigeria, Yemen, and so forth. Moreover – except for hard-core deniers of climate change, mostly on the far right – most people are now convinced that our world is confronted with a ‘climate crisis’ that has enormous impact on the global eco-system, on migration flows and, more generally, on our futures; this new awareness was mainly triggered by the bottom-up global social movement ‘Fridays for Future’, with its young female Swedish leader Greta Thunberg.2 Sadly, the financial crisis of 2008 and subsequent austerity politics have not led to substantial reforms of the global finance system and economy but have instead continued to increase global and local economic inequalities significantly; the full impact of new social media on (dis)information, on both fact-finding and the dissemination of ‘alternative facts’ and ‘fake news’, is only slowly being understood. All of these and many other phenomena are causing and substantiating uncertainty and insecurity; they are also being instrumentalized by far-right populist parties to fuel ever more and wilder conspiracy theories, to create fear and propagate apocalyptic scenarios.

Indeed, who would have predicted the victory of the ‘Leave Campaign’ (leading to Brexit) or Donald Trump’s election to President in 2014? Or the huge impact of the many racist, nativist and misogynist slogans uttered by Trump on Twitter or during speeches – such as ‘Lock her up!’ or ‘Crooked Hillary’ – launched against his opponent Hillary Clinton during the election campaign 2016 while accusing her of having broken laws during her appointment as Secretary of State 2008–2012 – or ‘Send her back!’ – calling on the Somali-born US citizen, Muslim Congresswoman Ilhan Omar to stop criticizing him or otherwise leave the country? Or that such slogans would resonate so well, be repeated by millions of US citizens, shouted like a mantra at election rallies, thus mobilizing the masses? There seems to be no end to Donald Trump’s (and many other far-right populist leaders’) lies, insults and discriminatory utterances, all of which have been widely publicized, discussed, scandalized and opposed – and have become normalized and entered mainstream discourse. And yet, as political scientist Paul Jackson (2019) maintains, ‘Trump’s shoot-from-the-hip public persona is a carefully constructed device, designed to consciously and deliberately break liberal taboos, setting an example to others that they can do likewise’.3 Hence, following philosopher Paul Feyerabend, it seems that ‘anything goes’!

This has become possible through – and is contingent on – the convergence of several distinct developments, such as the deepening cleavages in society, tendencies of renationalization as a response to migration movements, and, most importantly, a loss of trust in liberal democracy and its institutions as well as the above-mentioned (ab)use of social media. Are we thus dealing with a new ‘digital fascism’, as suggested by Fielitz and Marcks (2019, 2), in which ‘the masses are the engine of their own manipulation?’. This interpretation implies that social media has created new orders of perception in which liberal perspectives are superseded and authoritarian perspectives receive a boost. Or are we generally dealing with a ‘post-truth politics’ (Block 2019, 74)? As Nadler (2019, 8) argues, polling indicates that trust in major news sources diverges sharply by political party preference. Indeed, an October 2018 Gallup poll, as Nadler (ibid.) exemplifies, found that 76% of self-identifying Democrats had a ‘great deal’ or ‘fair amount’ of trust and confidence in mass media, while only 21% of Republicans responded similarly. Traditional quality media (TV, broadsheets, and so forth) are similarly defamed as ‘fake news’ or Lügenpresse by the far-right populist party in Germany, Alternative für Deutschland (AfD). I will come back to the interdependence between far-right politics and (social) media later on, both in this chapter and the remainder of this book.

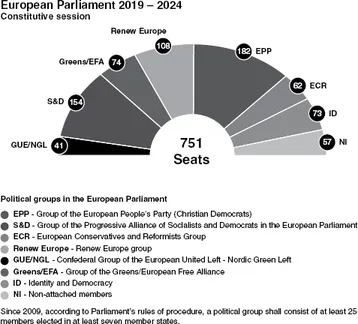

At the same time, the apparent chaos in UK politics while Britain negotiated its exit from the EU as well as its relationship thereafter has led to much greater cohesion and unity amongst the remaining 27 member states than anybody would have expected. The results of the most recent European Parliament elections (23–26 May 2019) clearly indicate that both the European People’s Party (EPP) and the Progressive Alliance of Socialists and Democrats (S&D) lost a number of seats compared to the 2014 election. The far right, however, made major gains, but less than predicted in many opinion polls (see Chapter 2). Moreover, the Green Party and the Liberal Party also won many seats; thus, the long-term coalition between the EPP and the S&D no longer holds a majority, and new alliances and coalitions will have to be negotiated (see Figure 1.14). British MEPs left the European Parliament following the UK’s exit on 31 January 2020, and this, of course, causes more uncertainty, more hope and fear, more negotiations and changes. Nevertheless, although Eurosceptic voices in other EU countries are still many and loud, they are no longer campaigning to leave the EU; they have shifted towards strengthening national sovereignty without cutting all ties to the EU.

Figure 1.1 Political groups in the European Parliament, after the election in May 2019

Accordingly, the latest Eurobarometer Survey from spring 2019 states that ‘the European sense of togetherness does not seem to have weakened. Continued support for EU membership goes with a strong belief (68%) that EU countries overall have benefited from being part of the EU – equaling the highest level recorded since 1983’.5 In addition, 61% of respondents say their country’s EU membership is a good thing. However, about 50% of EU respondents feel things are not going in the right direction in either the EU or their own country; that said, half of the respondents (51%) believe their voice does count in the EU. In contrast to the frequently explicitly xenophobic campaigns of many conservative mainstream and far-right parties, the top priorities of EU citizens have gradually changed – from uncertainty and fear of immigration as the main agenda, to economy and growth (50%) as well as youth unemployment (49%).6

Nevertheless, the Bulgarian political scientist Ivan Krastev maintains in his widely acclaimed book After Europe (Europadämmerung) (2017) that migration remains the single most important factor behind the rising discontent in Eastern and Western European countries and the significant cleavage between them. It is not the numbers of refugees and migrants that are of such importance, he continues, it is the brain drain from Eastern European countries, with millions of Poles, Czechs, Bulgarians, Slovaks and Romanians having left and continuing to leave their homes, leaving many people afraid that their culture, language and traditions might literally die out. This is why, Krastev argues, they close their borders to migrants and refugees coming from elsewhere, especially if the latter are Muslim; they are convinced that such people do not belong in Europe and actually threaten European traditions and an allegedly homogenous European culture.

It is therefore not surprising that manifold tendencies of renationalization across the EU and beyond should be interpreted as a consequence of the above; tendencies of creating ever new borders and walls, of linking the nation state and citizenship (naturalization) with nativist (frequently gendered and fundamentalist religious) body politics which lie at the core of far-right populist ideologies. We are experiencing a revival of the ‘Volk’ and the ‘Volkskörper’ in the separatist rhetoric of far-right populist parties, for example, in the US, Ukraine, Russia, Greece, Italy, Poland, Austria, the UK as well as Hungary (to name just a few). At the same time, very real walls of stone, brick and cement are also being constructed to keep out the ‘Others’, who are defined as different and deviant. Body politics are therefore integrated with border politics – in what could be labelled as the racialization of space (Wodak 2020a).

Analysing the Micro-Politics of Right-wing Populism

To avoid misunderstandings, I start off with a working definition of ‘far-right populism’, which will be discussed in more detail in Chapter 2. Generally, far-right populism attempts to reduce social and economic structures in their complexity and proposes simple explanations for complex and often global developments.7 In doing so, far-right populist discourses oppose ‘the true people’ to an allegedly corrupt ‘élite’ and routinely draw on well-known and established stereotypes of ‘the Other’ and ‘the Stranger’, whose discursive and socio-political exclusion is supposed to create a sense of community and belonging within the allegedly homogenous ‘people’ or ‘Volk’ (ethnos). The fact that these ‘strangers’ may, indeed, be right at the middle of the respective society marks far-right populism as a pseudo-democratic battleground for internal conflicts of interest within that society. The real political and economic contradictions, however, are not addressed directly, since far-right populism as an ideology seeks not to situate social conflict where it originates but to obscure or externalize it.

Of course, much research in the social sciences provides ample evidence for the current rise of far-right populist movements and related political parties in most EU member states and beyond. While the first edition of this book was written and published at a time when the forms and styles of political rhetoric had taken on a ‘soft’ and frequently coded veil for its xenophobic, racist and antisemitic, exclusionary and anti-elitist politics since 1989 – often labelled as ‘the Haiderization of politics’, named after the former leader of the Austrian Freedom Party (Freiheitliche Partei Österreich, or FPÖ), Jörg Haider – we are now confronted with a much more explicit, aggressive and indeed shameless rhetoric and politics of fear.

In this book I can certainly not cover all the complex phenomena associated with far-right populism; instead, I focus on the micro-politics of such parties – how they actually produce and reproduce their ideologies and exclusionary agenda in everyday politics, in the (social) media, in campaigning, in posters, slogans and speeches. Ultimately, I am concerned with how they succeed (or fail) in sustaining their electoral success. The dynamics of everyday well-staged performances frequently transcend careful analytic categorizations; boundaries between categories are blurred and flexible, open to change and ever-new socio-economic developments.

The following broad assumptions frame this book:

- All far-right populist parties instrumentalize some kind of ethnic, religious, linguistic or political minority as a scapegoat for most if not all current woes in society and subsequently construe the respective gro...