eBook - ePub

Wisconsin and the Civil War

Ronald Paul Larson

This is a test

Compartir libro

- 224 páginas

- English

- ePUB (apto para móviles)

- Disponible en iOS y Android

eBook - ePub

Wisconsin and the Civil War

Ronald Paul Larson

Detalles del libro

Vista previa del libro

Índice

Citas

Información del libro

Wisconsin troops fought and died for the Union on Civil War battlefields across the continent, from Shiloh to Gettysburg. Wisconsin lumberjacks built a dam that saved a stranded Union fleet.

The Second Wisconsin Infantry suffered the highest percentage of battle deaths in the Union army. Back home, in a state largely populated by immigrants and recent transplants, the war effort forced Wisconsin's residents to forge a common identity for the first time. Drawing on unpublished letters and new research, Ron Larson tells Wisconsin's Civil War story, from the famous exploits of the Iron Brigade to the heretofore largely unknown contributions of the Badger State's women, African Americans and Native Americans.

Preguntas frecuentes

¿Cómo cancelo mi suscripción?

¿Cómo descargo los libros?

Por el momento, todos nuestros libros ePub adaptables a dispositivos móviles se pueden descargar a través de la aplicación. La mayor parte de nuestros PDF también se puede descargar y ya estamos trabajando para que el resto también sea descargable. Obtén más información aquí.

¿En qué se diferencian los planes de precios?

Ambos planes te permiten acceder por completo a la biblioteca y a todas las funciones de Perlego. Las únicas diferencias son el precio y el período de suscripción: con el plan anual ahorrarás en torno a un 30 % en comparación con 12 meses de un plan mensual.

¿Qué es Perlego?

Somos un servicio de suscripción de libros de texto en línea que te permite acceder a toda una biblioteca en línea por menos de lo que cuesta un libro al mes. Con más de un millón de libros sobre más de 1000 categorías, ¡tenemos todo lo que necesitas! Obtén más información aquí.

¿Perlego ofrece la función de texto a voz?

Busca el símbolo de lectura en voz alta en tu próximo libro para ver si puedes escucharlo. La herramienta de lectura en voz alta lee el texto en voz alta por ti, resaltando el texto a medida que se lee. Puedes pausarla, acelerarla y ralentizarla. Obtén más información aquí.

¿Es Wisconsin and the Civil War un PDF/ePUB en línea?

Sí, puedes acceder a Wisconsin and the Civil War de Ronald Paul Larson en formato PDF o ePUB, así como a otros libros populares de Geschichte y Nordamerikanische Geschichte. Tenemos más de un millón de libros disponibles en nuestro catálogo para que explores.

Información

Categoría

GeschichteCategoría

Nordamerikanische Geschichte1

WISCONSIN BEFORE 1860

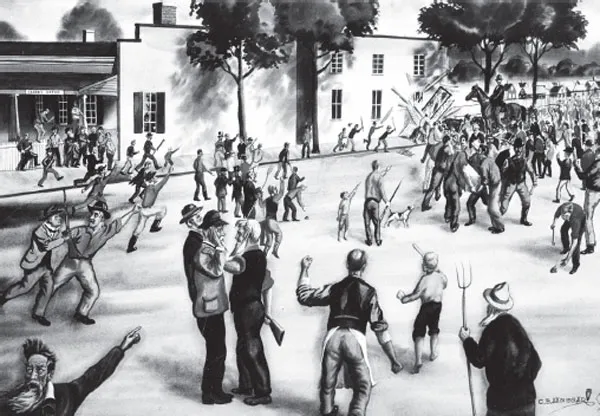

In the late afternoon of March 11, 1854, a mob of about four thousand men gathered outside the Milwaukee county jail. They were angry and on the verge of violence. Inside the jail, Joshua Glover, an African American man, born into slavery, was held alone in a cell and injured, dry blood encrusting his scalp. He had been captured the night before and suffered a severe head wound when U.S. Marshal Charles C. Cotton hit him in the head with handcuffs.1

Around 5:00 p.m., some in the crowd rushed the jail. One man kicked in the outer door. Others used pickaxes to make a hole in the wall next to the jail door. Men yelled for keys. James Angove, a mason, heard the call for keys and noticed lumber “all over the street” at nearby St. John’s Cathedral, which was under construction. He picked up a beam about six inches in diameter and twenty feet long and shouted to the crowd, “Here’s a good enough key.” About twenty men grabbed hold of the beam and battered in the jail door. On the ground floor, Glover undoubtedly heard everything. He knew the men were trying to get to him. The undersheriff, S.S Conover, tried to prevent the mob from taking Glover, but men pulled him away. Glover was taken from his jail cell. As he emerged from the building, he waved his hat at the crowd. He was a free man.2

Escorted by one thousand men, Glover was put in a waiting wagon and driven from Wisconsin Street to East Water Street and then to Walkers Point Bridge where John A. Messenger, a Democrat, put Glover into his buggy and drove as fast as he could out of the city, heading west.3

A postwar engraving of Joshua Glover. Wisconsin Historical Society.

A contemporary artist’s rendering of the rescue of Joshua Glover. Milwaukee Country Historical Society.

In the end, Glover, a slave who had escaped two years earlier from St. Louis and was working at a sawmill outside Racine, Wisconsin, when he was captured, gained his freedom. Sometime in the first two weeks of April 1854, with the help of abolitionists, Joshua boarded a steamer in Racine and made it to Canada, where he married and lived as a free man for the rest of his life.4

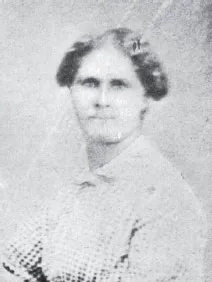

Joshua Glover was not the first fugitive slave to use the Underground Railroad in Wisconsin. In all likelihood, it was Caroline Quarlls, a sixteen-year-old fugitive slave who, like Glover, was also from St. Louis. A house slave who, in her own words, was “treated well enough for a slave,” although she had been “whipped,” fled on July 4, 1842, after saving $100.

Caroline was fair-skinned. She most likely was an octoroon—a person who is one-eighth African American. Passing as white, she booked passage on a steamboat from St. Louis to Alton, Illinois. Arriving in Alton, she was in a free state but still in danger of capture. After some time in Alton, she took a stagecoach to Milwaukee, arriving in early August. Pursued by bounty hunters, she was hidden by abolitionists in Milwaukee, Prairieville (now Waukesha) and Spring Prairie. In early September, Lyman Goodnow, a Prairieville abolitionist, escorted her to Chicago, across Indiana and Michigan to Detroit, where she crossed into Canada. In Canada, she married another escaped slave, Allen Watkins, and raised six children with him in Sandwich (modern Windsor), Ontario, Canada. She lived until 1892.5

The same year that Glover made his escape to Canada, a father and two children passed through Chilton, Wisconsin, aided by Stockbridge Indians, who saw them safely to Green Bay and then to Canada by ship. Between 1842 and 1861, it is estimated that more than one hundred slaves used the Underground Railroad in Wisconsin to escape to freedom. Antislavery sentiment in Wisconsin was strong.6

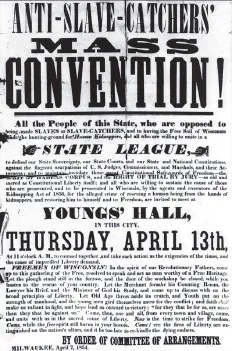

The man who spearheaded the breakout of Glover, the abolitionist newspaper editor Sherman Booth, was arrested by federal authorities for assisting in the escape of a fugitive slave. This was a violation of the 1850 Fugitive Slave Act, which required people to help return escaped slaves to their owners. The Fugitive Slave Act rallied antislavery sentiment in Wisconsin, as it did throughout the North. For Booth, it was the beginning of a six-year legal odyssey that resulted in the Wisconsin Supreme Court declaring the Kansas-Nebraska Act unconstitutional, the U.S. Supreme Court overturning the Wisconsin decision and reaffirming the constitutionality of the Fugitive Slave Act, and the Wisconsin state legislature passing the Wisconsin Declaration of Defiance in response to the U.S. Supreme Court decision—arguing that a state could declare a law unconstitutional in opposition to the U.S. Supreme Court. Two days before Abraham Lincoln’s inauguration in March 1861, President James Buchanan had Booth’s fines remitted, allowing his release from federal confinement.7

The only known image of Caroline Quarlls Watkins, taken when she lived in Sandwich, Ontario. Wisconsin Historical Society.

THE CREATION OF THE REPUBLICAN PARTY

A lot happened in Wisconsin in 1854. Less than three months after the rescue of Joshua Glover and the arrest of Booth, the Kansas-Nebraska Act became law. The Kansas-Nebraska Act, the brainchild of Illinois senator Stephen A. Douglas, specified that settlers in the Kansas and Nebraska Territories would decide whether to be slave or free when their state entered the Union. This idea of popular sovereignty nullified the Missouri Compromise of 1820, which prohibited slavery north and west of 36°30 latitude, Missouri’s southern border.8

The Kansas-Nebraska Act created an anti-Nebraska movement in Wisconsin and throughout the North. People of all political persuasions—Whig, Free Soil and Democrat—opposed the opening up of the territories to slavery. In early 1854, political leaders across Wisconsin called for meetings to oppose the act. One of these meetings, held in Ripon, Wisconsin, on March 20, 1854, is considered one of the founding meetings of the Republican Party.9

Many years later, George F. Lynch remembered when, as a twenty-seven-year-old, he met his friend Alvin E. Bovay on a street in Ripon. Bovay told him, “You’ve got to come to our meeting in the schoolhouse tonight. We’re going to organize our party.” Lynch and sixteen other men, including Bovay, met “in the little old schoolhouse” after Lynch’s sister, who was the schoolteacher, dismissed her students for the day. In Lynch’s view, Bovay was “the brainiest man” in Ripon. Bovay had been thinking about naming the proposed new political party, which would combine all the parties opposed to the extension of slavery, “Republican.” At the meeting Lynch suggested “Democratic-Republican.” There were other suggestions, but Bovay’s name won. “And it was largely due to his facile pen and his connection with the leading newspapers in the country,” Lynch noted, that the name Republican was adopted by the new party first in Wisconsin and later throughout the country.10

Poster for an Anti-Slave-Catchers’ meeting at Youngs’ Hall in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, on April 13, 1854. Wisconsin Historical Society.

The Republicans broke over the political scene like a tidal wave. In the elections of 1854, the Wisconsin state legislature elected the country’s first Republican U.S. senator, Charles Durkee of Kenosha. Two years later, the Republican Party held its first national convention in Philadelphia, and its presidential candidate, John C. Frémont, won Wisconsin with 55 percent of the vote and ten of the sixteen northern states. Governor Alexander Randall, reelected in 1859 to a two-year term, also declared himself a Republican. As the country rapidly approached the crisis over slavery and disunion, Republicans greatly outnumbered Democrats in the political landscape of Wisconsin.11

2

WISCONSIN IN 1860

In 1860, Wisconsin had been a state for twelve years. Most of the state’s 775,000 people lived along Lake Michigan and in the southern counties. Milwaukee, known as the “Cream City” because of the light-colored brick used in many of its buildings, was the largest city in the state with more than 45,000 people. Initially settled by French-Canadian fur traders in 1795, Milwaukee was located on the shore of Lake Michigan at the confluence of three rivers: the Milwaukee, the Menomonee and the Kinnickinnic. Milwaukee grew rapidly. Because the public lands office was located there, it became the favored landing place for settlers. When it was incorporated in 1846, it equaled Chicago in size.12

The population of Wisconsin was a varied one. A little more than a third of the people living in the state were foreign born. Of these, 44 percent were from the German states. This was, by far, the largest group of immigrants, the result of a wave of German immigration that occurred between 1846 and 1854. It was due in part to the Wisconsin Commission of Emigration, which encouraged European immigrants to settle in Wisconsin between 1852 and 1855. Pamphlets were published in German, Norwegian, Dutch and English and distributed across Europe and the port cities of the East. This German migration brought industrial skills, Catholicism and liberal politics. Milwaukee became a center for machinery and metalworking industries and, because Germans liked their beer, a center for grain trading and brewing. Their importance is demonstrated by the fact that in 1860, there were twenty German-language newspapers published in Wisconsin.13

A view of Court and Milwaukee Streets in Janesville, circa 1868–71. Wisconsin Historical Society.

Of the remaining immigrants, the next largest groups were from Ireland and Great Britain, 50,000 and 44,000, respectively. Norway also provided large numbers of immigrants: 21,442. Many of these immigrants settled in Milwaukee County, where the foreign born outnumbered the “native” born 33,144 to 29,374.

The remaining two-thirds of the people in the state were born in the United States—about half of them in Wisconsin. The others migrated from elsewhere in the country. New York State provided 120,637, Ohio 24,000 and Pennsylvania 21,043. New Englanders were also numerous, numbering 54,000. Southerners, in contrast, made up less than 1 percent of the population.

This diverse population of East Coast Yankees and immigrants from central and northern Europe reacted differently to the reform movements of the first half of the century—particularly to the question of slavery and abolition.

The antislavery movement in Wisconsin was made up mainly of former Yankees and the so-called “Forty-Eighters,” liberal reformers who had fled Europe after the failure of the 1848 revolutions. Carl Schurz was Wisconsin’s best known Forty-Eighter. Many German and Irish immigrants in Wisconsin feared emancipation, however, thinking it would flood the North with cheap labor that would compete for jobs.

The “free colored” population was small in Wisconsin, numbering only 1,171. Of these, 737 were classifi...