![Air Power in Three Wars: World War II, Korea, Vietnam [Illustrated Edition]](https://img.perlego.com/books/RM_Books/inde_pub_group_sqonxaw/9781786250728_300_450.webp)

eBook - ePub

Air Power in Three Wars: World War II, Korea, Vietnam [Illustrated Edition]

General William W. Momyer USAF

This is a test

Compartir libro

- 278 páginas

- English

- ePUB (apto para móviles)

- Disponible en iOS y Android

eBook - ePub

Air Power in Three Wars: World War II, Korea, Vietnam [Illustrated Edition]

General William W. Momyer USAF

Detalles del libro

Vista previa del libro

Índice

Citas

Información del libro

[Includes over 130 illustrations and maps]

This insightful work documents the thoughts and perspectives of a general with 35 years of history with the U.S. Air Force – General William W. Momyer. The manuscript discusses his years as a senior commander of the Air Force – strategy, command and control counter air operations, interdiction, and close air support. His perspectives cover World War II, the Korean War and the Vietnam War.

Preguntas frecuentes

¿Cómo cancelo mi suscripción?

¿Cómo descargo los libros?

Por el momento, todos nuestros libros ePub adaptables a dispositivos móviles se pueden descargar a través de la aplicación. La mayor parte de nuestros PDF también se puede descargar y ya estamos trabajando para que el resto también sea descargable. Obtén más información aquí.

¿En qué se diferencian los planes de precios?

Ambos planes te permiten acceder por completo a la biblioteca y a todas las funciones de Perlego. Las únicas diferencias son el precio y el período de suscripción: con el plan anual ahorrarás en torno a un 30 % en comparación con 12 meses de un plan mensual.

¿Qué es Perlego?

Somos un servicio de suscripción de libros de texto en línea que te permite acceder a toda una biblioteca en línea por menos de lo que cuesta un libro al mes. Con más de un millón de libros sobre más de 1000 categorías, ¡tenemos todo lo que necesitas! Obtén más información aquí.

¿Perlego ofrece la función de texto a voz?

Busca el símbolo de lectura en voz alta en tu próximo libro para ver si puedes escucharlo. La herramienta de lectura en voz alta lee el texto en voz alta por ti, resaltando el texto a medida que se lee. Puedes pausarla, acelerarla y ralentizarla. Obtén más información aquí.

¿Es Air Power in Three Wars: World War II, Korea, Vietnam [Illustrated Edition] un PDF/ePUB en línea?

Sí, puedes acceder a Air Power in Three Wars: World War II, Korea, Vietnam [Illustrated Edition] de General William W. Momyer USAF en formato PDF o ePUB, así como a otros libros populares de History y Military & Maritime History. Tenemos más de un millón de libros disponibles en nuestro catálogo para que explores.

Información

Categoría

HistoryCategoría

Military & Maritime HistoryCHAPTER I — STRATEGY

My vantage point in World War II, as Commander of the 33rd Fighter Group in North Africa, Sicily, and Italy, gave me a good view of more German and Italian Fighters than I really cared to see, but not many opportunities to witness the making of Allied air strategy. However, every pilot knew that our strategy embraced two fundamental features: attacks against the enemy heartland (with which I had little to do, either in Europe or the Pacific) and participation with surface forces to destroy the opposing forces or cause them to surrender. The first priority of our air strategy was to gain control of the air. Then we concentrated our efforts on isolating the battlefield and providing close air support. This air strategy provided flexibility to the Allied armies in their ground campaigns and guaranteed a minimum of interference from the German Air Force. By the time I returned to the U.S. in 1944 to become Chief of Combined Operations on the Army Air Forces Board, our airpower had virtually destroyed the Luftwaffe in the Mediterranean through air-to-air engagements and attacks on airfields and logistical bases; and we had repeatedly cut the enemy’s air, sea, and land lines of communication, enabling our armies to capture North Africa and Sicily and to invade southern Italy.

At about the time I was leaving Europe, our B-29s in the Pacific were beginning their attacks against Japan from bases in China. In November 1944, B-29s from China and the Marianas raided Tokyo, and in March 1945, Major General Curtis E. Lemay began the decisive campaign of night, low-level incendiary attacks. The air war in the Pacific culminated with the dropping of atomic bombs on 6 and 9 August, events which profoundly affected U.S. air strategy.

NUCLEAR WEAPONS AND TACTICAL AIR FORCES

With nuclear weapons a reality in the late forties and early fifties, many strategists urged that we evaluate all military forces in light of their ability to contribute to a general nuclear war.{1} But other planners disagreed. A reduction in the size of U.S. armed forces, and our increasingly heavy emphasis on nuclear weapons, prompted a debate which brought out basic differences among the service chiefs and within the Air Force itself, I was uniquely situated to view this debate. Having been assigned as Assistant Chief of Staff of Tactical Air Command in 1946, I was at Hq TAC when the Air Force separated from the Army in 1947, and I remained with TAC until going to the Air War College in 1949.

The Army maintained that substantial conventional forces would be needed to fight limited wars. To evaluate all forces on the basis of their contribution to a general nuclear war with the Soviet Union would be imprudent, they said. Several air strategists replied that with nuclear weapons, it no longer made sense to maintain large conventional forces since such forces couldn’t survive in a nuclear war. Furthermore, airpower’s capacity to eliminate the command centers of an enemy made extensive surface campaigns unnecessary. Airmen conceded that some conventional forces would be needed for limited wars, but said that these forces need only be large enough to force the enemy into tactics that would produce a target for our nuclear weapons. They doubted, too, that a limited war could remain limited indefinitely. Either the employment or the threat of nuclear weapons would halt the conflict, or the conflict would rapidly expand to a general war.

But even within the Air Force during the late 1940s and early 1950s, there was fundamental difference of views on limited war. Many tactical airmen, including Lieutenant General Elwood R. Quesada and Major General Otto P. Weyland, believed that non-nuclear war was the most probable type of future conflict. These airmen argued that limited wars of the future would be fought without nuclear weapons because national leaders would realize that once nuclear weapons were introduced, it would become impossible to prevent the escalation of any conflict into general nuclear war: If the initial employment of small nuclear weapons didn’t produce the desired effects, commanders would surely strike additional targets with more and larger weapons. With the explosion of a nuclear device by the Soviet Union in 1949, it was clear that nuclear weapons were no longer a U.S. monopoly, and tactical airmen argued that we had to prepare for limited wars in which both sides would voluntarily refrain from using nuclear weapons. We had to maintain sizeable tactical forces capable of fighting with conventional weapons.

At a time when the Air Force was shrinking and funds were short, though, it wasn’t easy to find money for conventional tactical weapon systems. Understandably, most of the Air Force budget was earmarked for that part of the force which would have to deter or win a general nuclear war with the Soviet Union.{2} Strategic forces received most of the Air Force dollars, and only those tactical forces that had a nuclear capability could demand and get substantial funding. Other elements of the tactical force had to forego modernization.

Despite our national emphasis on strategic nuclear forces, tactical airmen continued to press for the restoration of a non-nuclear capability such as we had possessed during World War II. They stressed that the type of command and control system needed in a theater nuclear war was the same as that needed for non-nuclear war. If the tactical air force were to conduct a theater nuclear campaign, it would require a modernized command and control system and procedures for close coordination with ground forces, irrespective of the intensity and duration of the conflict. To carry out a theater nuclear strategy, precise control of airpower would be essential to prevent fallout and casualties to our own air and ground forces.

It seemed to these airmen that the essential elements of a tactical air force would be the same whether the force were designed for a nuclear or non-nuclear situation. They believed, further, that although additional aircrew training would be necessary for some aspects of nuclear operations, basic tactical skills would remain the same. Tactical training would simply omit certain aspects of non-nuclear weapons delivery and emphasize a few basic techniques such as dive bombing and low altitude bombing which were common to tactical nuclear and non-nuclear weapons delivery. Thus it would be feasible to maintain non-nuclear proficiency without degrading an aircrew’s ability to deliver tactical nuclear weapons.

In the years preceding the Korean War, tactical air forces were being cut back in accordance with the overall national policy following World War II. Even with these reduced forces and the emphasis on nuclear operations, however, there remained a high residuum of experience in non-nuclear operations from World War II. Despite a shortage of equipment, the high level of experience permitted expansion and modernization of the tactical air forces when they were needed in Korea.

KOREAN WAR—A DILEMMA

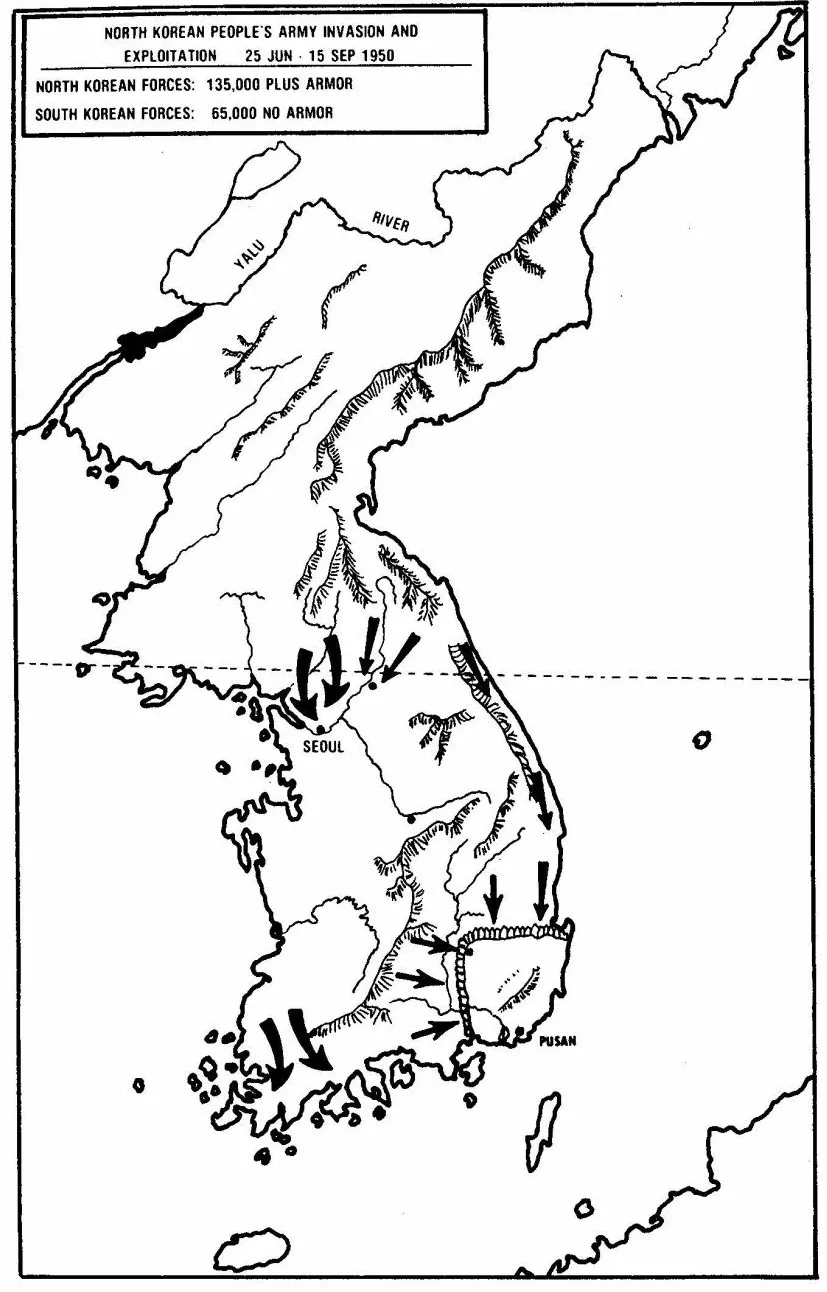

When the North Koreans invaded South Korea on 25 June 1950,{3} U.S. defense planners carefully evaluated our strategy for conducting limited nuclear war: Was the strategy feasible in Korea? Would it be acceptable to our allies? On both counts the strategy was deficient. There were few attractive targets for tactical nuclear weapons because of the lack of concentration of North Korean forces and the many alternative routes of advance afforded the enemy by the Korean terrain. Further, the Allied forces were retreating in such disarray that it was unrealistic to suppose that we could promptly turn them around for a counterattack in which nuclear weapons could provide the basic firepower.

By the time the Allied forces had withdrawn into the Pusan perimeter, the employment of nuclear weapons was not a realistic option because of the poor targets and the attitude of our allies toward these weapons. Air strategy, then, was based on non-nuclear weapons, and it comprehended the same missions that tactical air forces had performed in World War II. With the North Korean Air Force neither a significant threat nor within range of the retreating Allied forces, air strategy focused initially on chopping off the supply lines to the North Korean ground forces, making it impossible for these divisions to mount a sustained offensive against the Pusan perimeter. Also a part of this strategy, of course, was a direct attack against assaulting ground forces. American airmen maintained complete control of the air for the Inchon invasion and the subsequent advance into North Korea. Air strategy was an essential part of the joint strategy.

When the Chinese communists invaded Korea in October 1950,{4} however, the Allies had to make major revisions in their strategy. As the enemy forces moved across the border, it appeared that airpower would have to be employed much more broadly to reduce the numerical superiority of the Chinese. MacArthur proposed that the bridges and lines of communication used by Chinese entering North Korea be subjected to sustained air attack. He felt it imperative to deny these forces the sanctuary they then enjoyed.

Among airmen the question of how Chinese and Soviet airpower could be contained along the Yalu was debated with vigor. Some airmen, including Major General Emmett O’Donnell, Jr., believed it would be necessary to strike the airfields and engage the fighters deep in the rear areas if control of the air were to be established. (All agreed that such control was absolutely essential to our retreating ground forces, who were so badly outnumbered that many Americans were questioning whether the Allies could hold any position in Korea.){5} O’Donnell and others insisted that the enemy must not be permitted a sanctuary from which to attack the Allied air forces and our forward bases.

After considerable deliberation, the Joint Chiefs recommended that Far East Command’s air offensive not be extended beyond the Yalu into Manchuria unless the enemy launched massive air attacks against our forces, in which event American airmen would destroy the airfields from which the attacks originated.{6} For airmen in Korea, the recognition of an enemy sanctuary across the Yalu posed a terrific problem: How were we to contain a numerically superior enemy fighter force when all of our forward bases and lines of communication were open to attack?

YALU—CONTAINMENT OF MIGS

Clearly we had to shift from an air strategy oriented primarily toward close support of our ground forces to a new strategy featuring (1) offensive fighter patrols along the Yalu, (2) attacks against forward staging bases from which MIGs might strike 5th Air Force airfields and the 8th Army, and (3) intensive attacks against the main supply lines of the advancing Chinese army. These air operations became the primary means of preventing the enemy’s air and ground forces from pushing the Allied army out of Korea. The 8th Army’s objective was to hold, rather than to defeat or destroy, the opposing ground forces. This objective evolved from the pragmatic observation that a much larger ground force would be needed to defeat the enemy. Such a ground campaign would be too long and too costly.

Maintaining continuous pressure on the enemy’s rear area, his lines of communication, and his engaged troops, airpower helped persuade the enemy to cut his losses. The North Koreans were finally persuaded that they should seek an end to the war at the conference table rather than on the battlefield, and negotiations ended the conflict on 27 July 1953 after three years of fighting.{7}

IMPACT OF KOREAN WAR

With the end of the Korean War, defense planners re-evaluated our strategy for employing airpower. Perhaps the paramount question of the time was whether we should prepare to fight limited as well as general wars. After the agony and expense of Korea, an understandably popular position was that we would never fight, nor should we prepare to fight, another war like Korea. Adding to the popularity of this position was the fact that it could be used to justify a reduction in defense forces and expenditures. If a limited war should break out, proponents said, nuclear weapons could end it quickly. But the way to prevent such wars would be to maintain military and political pressure against potential instigators. If the outside support for a limited conflict were neutralized, the conflict itself would soon die for lack of weapons and other resources. Most airmen consented to the idea that nuclear weapons should be the basis of our defense strategies, but the Army and Navy maintained that limited conflict was most likely and that limited wars would, at least initially, be fought with conventional weapons.

Once again nuclear forces were accepted as the dominant element of our national defense, and all forces were evaluated in light of their usefulness in the event of nuclear conflict. Resources allocated to non-nuclear forces were sufficient only to fight a brief, very limited war. Throughout the mid-fifties, all of the services accepted the nuclear war premise in their yearly budget arguments. The Army, however, continued to press for sizeable forces capable of fighting a limited non-nuclear conflict. Army spokesmen feared that the dominant concern about nuclear war was overshadowing the need for ground forces capable of fighting in situations other than nuclear battlefields in Europe. Nevertheless, the survivability of forces on a nuclear battlefield continued to be a major concern of most strategists during the period.

THE FRENCH IN INDOCHINA

In 1953 on the eve of Dien Bien Phu, U.S. defense planners differed widely in their opinions about the appropriate role of airpower in low scale conflict. Several Army planners felt that airpower could operate only as a supporting force. The main role of airpower was, in their view, the delivery of supplies, equipment, and personnel, and the support of civic action measures. Whatever firepower was required to deal with guerrilla actions wouldn’t demand the sophisticated weapons of our airpower arsenal. Based on these views of airpower, and the experience of ground warfare in Korea, the prevailing view in the U.S. military establishment was that U.S. forces should not become engaged in Vietnam and Laos; rather, we should continue to support the French in their expansion of Vietnamese forces to counterbalance the Viet Minh threat.

However, some elements of the U.S. military were not convinced the French were making sufficient progress in building self-sufficiency into the Vietnamese armed forces. They felt that the French were placing too much emphasis on training for a conventional conflict rather than a counterinsurgency war. These views were based largely on Britain’s experience in Malaya where there were no large, conventional ground actions. Almost all engagements were small, brief counter-guerrilla actions. The success of the British in containing and eventually eliminating the insurgents in this conflict convinced many in the U.S. military that this was the strategy the French should pursue in containing the Viet Minh. Airpower had played a limited role in the Malayan insurgency, and this fact was used as evidence that airpower would not be critical for the success of the French in Indochina.

We should have learned from the French defeat at Dien Bien Phu on 7 May 1954, however, that the French were fighting a much different foe than the British had faced in Malaya. For the British, it was relatively simple to shut off most of the external support to the Ma...