eBook - ePub

Joining God, Remaking Church, Changing the World

The New Shape of the Church in Our Time

Alan J. Roxburgh

This is a test

Compartir libro

- 128 páginas

- English

- ePUB (apto para móviles)

- Disponible en iOS y Android

eBook - ePub

Joining God, Remaking Church, Changing the World

The New Shape of the Church in Our Time

Alan J. Roxburgh

Detalles del libro

Vista previa del libro

Índice

Citas

Información del libro

Exhausted with trying to "fix" the church? It's time to turn in a new direction: back to the Holy Spirit. In this insightful book, internationally renowned scholar and leader Alan Roxburgh urges Christians to follow the Spirit into our neighborhoods, re-engage with the mission of God, and re-imagine the whole enterprise of church. Joining God, Remaking Church, and Changing the World can guide any church—large or small, suburban or urban, denomination-level or local parish — to become a vital center for spirituality and mission.

Preguntas frecuentes

¿Cómo cancelo mi suscripción?

¿Cómo descargo los libros?

Por el momento, todos nuestros libros ePub adaptables a dispositivos móviles se pueden descargar a través de la aplicación. La mayor parte de nuestros PDF también se puede descargar y ya estamos trabajando para que el resto también sea descargable. Obtén más información aquí.

¿En qué se diferencian los planes de precios?

Ambos planes te permiten acceder por completo a la biblioteca y a todas las funciones de Perlego. Las únicas diferencias son el precio y el período de suscripción: con el plan anual ahorrarás en torno a un 30 % en comparación con 12 meses de un plan mensual.

¿Qué es Perlego?

Somos un servicio de suscripción de libros de texto en línea que te permite acceder a toda una biblioteca en línea por menos de lo que cuesta un libro al mes. Con más de un millón de libros sobre más de 1000 categorías, ¡tenemos todo lo que necesitas! Obtén más información aquí.

¿Perlego ofrece la función de texto a voz?

Busca el símbolo de lectura en voz alta en tu próximo libro para ver si puedes escucharlo. La herramienta de lectura en voz alta lee el texto en voz alta por ti, resaltando el texto a medida que se lee. Puedes pausarla, acelerarla y ralentizarla. Obtén más información aquí.

¿Es Joining God, Remaking Church, Changing the World un PDF/ePUB en línea?

Sí, puedes acceder a Joining God, Remaking Church, Changing the World de Alan J. Roxburgh en formato PDF o ePUB, así como a otros libros populares de Theology & Religion y Religion. Tenemos más de un millón de libros disponibles en nuestro catálogo para que explores.

Información

Categoría

Theology & ReligionCategoría

Religion PART I

The conversation is typical. You quickly sense the anxiety. On a phone or video conference, a team from a congregation or denominational office describes the challenge: how to make the change that will enable them to survive or grow again.

A denominational leader comes into town and wants a lunch meeting. As we catch up over sushi, he describes the situation in his region. Eventually he wonders if he needs to change to some other church, if they know something his group doesn’t.

The staff of another denomination describes a growing percentage of congregations hovering on the edge of viability. They can’t afford full-time clergy, and the people and their leaders are frozen with anxiety. Something has gone wrong, and people want answers.

I met with regional executives in Denver to discuss progress in a series of imaginative initiatives with some congregations. Little had happened. Not because they didn’t want to see the initiatives go forward, but because their time and energy were consumed addressing an increasing number of conflicts and dysfunctions among churches and leaders.

While such stories are not true for every congregation or church leader, they are more and more the norm. What they demonstrate is that Protestant churches have been in the midst of a great unraveling for quite some time.

In order to step into hope realistically, we have to pause to understand how we got to this stage and just what the unraveling means. Isaiah reminds Israel how it got into the situation in which it found itself. Time and again, they gave over their lives and identities to Egypt. They lost covenant faithfulness, and ended up in the long Babylonian captivity. These events did not just happen to Israel. The people and their leaders participated. In each situation, they placed their hope in the tactics of power or survival.

But Isaiah does not recall these stories to badger Israel. He does so as part of proposing an alternative reality, one in which God is present and active in the midst of the unraveling. We, too, need to revisit the stories of what got us to this place of unraveling, in order to see the future God is shaping. Part I of this book outlines the contours of what has happened over the last half-century, while part II proposes ways we can be transformed.

This is the story of a great unraveling. I tell it to clear the ground so we can inhabit a different future.

CHAPTER ONE

The Great Unraveling

My wife loves to knit. I’m bemused as I watch her work. She will knit for hours and then, with a great sigh, unravel a week’s worth of knitting. It’s hard to watch.

In our story, what is coming undone is the long, cherished tradition of the “Euro-tribal churches” across North America. I use this term with great intention, and I’ll take a moment to explain. The churches with which I have worked most closely and the ones with which this book deals most directly are those that trace to the great migrations from the United Kingdom and Europe over the past four to five hundred years, the churches that form the primary Christian groups in the United States and Canada. They created denominations shaped largely by ethnic and religious identities coming out of the fifteenth- and sixteenth-century reformations: Lutherans (Germany and Scandinavia), Episcopalians (England), Presbyterians (Scotland), United Church of Canada (Great Britain), Methodists and Baptists (England), Mennonites (the Netherlands and Germany), and so forth.

To a great extent these denominations were formed and expanded in the context of strong national and ethnic identities. For this reason, I characterize them as tribal and use the phrase Euro-tribal churches. It is important to note, but isn’t the subject of this book, that these Euro-tribal churches morphed and created a good number of “made in the Americas” denominations, such as Churches of Christ, Pentecostalism, and indigenous spin-offs like National Baptists or the African Methodist Episcopal Church. These are highly nuanced developments, running alongside the Euro-tribal story. Likewise, it is clear that the Roman Catholic Church, in its own migrations to North America, had to redefine itself as one denomination among many others. For multiple reasons—perhaps because its liturgical tradition and hierarchy better transcend national-cultural identities—it has seemed able to weather the unraveling more cohesively than the Protestant denominations.

For the Euro-tribal churches, the story of this unraveling goes back to the middle of the last century. Sociologist Hugh McLeod explains the lead-up to the breakdown this way:

In the 1940s and 1950s it was still possible to think of western Europe and North America as a “Christendom,” in the sense that there were close links between religious and secular elites, that most children were socialized into membership in a Christian society, and that the church had a large presence in fields such as education and welfare, and a major influence on law and morality.1

The 1940s and 1950s, while influenced by fears of external threats from Communism, were a golden period for these churches. World War II had been won, the Great Depression was over, democracy was prevailing in the midst of a Cold War. The West was ready to celebrate, to leave behind the hardships of the previous half-century. Most Protestant churches flourished in this environment, where it seemed just about everyone and everything was Christian. These churches symbolized the public and social conscience of the age. They were the government, education, economic, and professional leaders of the nation at worship. Young families embraced the new suburbs, churches filled, and denominations experienced their greatest era of new church development.

In this milieu these churches can hardly be blamed for seeing themselves as the center of society and assuming their proclamations and actions would lead to the redemption and betterment of society. They pursued growth with gusto, expanding new church development, filling seminaries, and extending corporate denominational structures offering cradle-to-grave, branded programs that branched across the continent. Donald Luidens paints this picture:

The corporate denomination “metaphor” … seems to be an apt representation of the organizational formula that saw the establishment and routinization of religious communions throughout the United States. The wide-open “religious marketplace” in the post-World War II era accelerated the development of this corporate model. Like competing businesses occupying a growing market niche, Protestant denominations around the country routinely perfected their production processes and marketing techniques. In these early years the level of competition was minimal and “success” was widespread. However, over time the religious marketplace became a crowded one, competition grew and success became elusive, which accelerated the transformation of the corporate denomination. …

[R]eflecting the imperialistic optimism of the age, the corporate model ushered in a worldwide vision for Christian ministry (symbolized in the title of the flagship Protestant journal of this era, the Christian Century). … The corporate model fuelled, and was in turn fuelled by, a Christianity that was outward-looking and expansionist.2

Few were aware of, or prepared for, the earthquakes to come. Just as the young church, after Pentecost, focused on reestablishing God’s reign within the narrative of Jerusalem and Judaism and could not see the ways the Spirit was about to unravel most of its assumptions, so the denominations failed to see the massive dislocations into which the Spirit would soon deliver them.

The Protestant story couldn’t hold the imagination or desires of post-war generations, so the ’60s exploded like a socio-cultural-religious Mt. St. Helens. As McLeod observes: “In the religious history of the West these years may come to be seen as marking a rupture as profound as that brought about by the Reformation. … The 1960s was an international phenomenon.”3

Throughout North America and Europe, we witnessed the Baby Boom, rising economic possibilities for huge swaths of the public, the Civil Rights Movement, the Vietnam War, the Sexual Revolution, the emergence of the self as the central source of meaning. Along with these came the Human Potential Movement, the Women’s Movement, a shrinking world with expanded religious options, the end of National Service in the United Kingdom, the expansion of higher education from elites to the middle classes, the suburbanization of society, and the proliferation of new media.

The changes went on and on, and their impact was massive and unexpected. Like the Babylonian captivity or the destruction of Jerusalem in 70 CE, these events resulted in massive dislocation. The churches were thrown into a world for which they were unprepared. The natural instinct is to fix what is broken and to get back to the stability and predictability they had known. But that world had been torn up.

By the late 1960s numerical growth for the mainline denominations had come to a screeching halt. Despite warnings from observers of culture such as Peter Berger and Gibson Winter, the churches were largely unprepared. They continued expanding national staff, building national headquarters, and marketing their branded programs.

Protestant churches have only continued to lose their place in the emerging cultural milieu. If anything, the change has picked up pace, unabated, over the proceeding decades. Despite claims that conservative, evangelical churches had found the secret to growth, there is now sufficient evidence that the primary reason conservative churches grew was defections from mainline churches. The conservative Protestant churches have experienced their own unraveling tsunami, just a little later.

This unraveling has manifested most keenly as a progressive loss of connection between the churches and the generations that emerged from the 1960s onward. Here are some illustrations:

• If you were born between 1925 and 1945, there is a 60 percent chance you are in church today.

• If you were born between 1946 and 1964, there is a 40 percent chance you are in church today.

• If you were born between 1965 and 1983, there is a 20 percent chance you are in church today.

• If you were born after 1984, there is less than a 10 percent chance you are in church today.

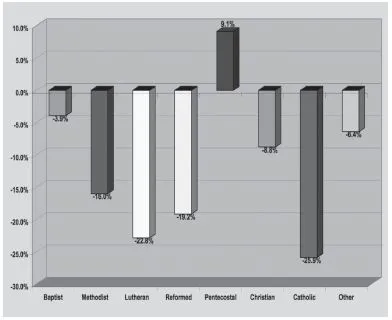

1990–2005 Growth or Decline as a Percentage of the Population by Denominational Family

Good News in Unlikely Places

Ultimately, it is my strong contention that the Spirit has been at work in this long unraveling. The Spirit is inviting these churches to embrace a new imagination, but the other one had to unravel for us to see it for what it was. In this sense the malaise of our churches has been the work of God. Allow me to spell out several implications for this proposal:

FIRST: If the Spirit has been at work in this long unraveling, then God is not done with the Euro-tribal, Protestant churches. In Scripture places of unraveling were preludes to God shaping a new future for God’s people. For instance, the persecutions of Acts 8 precipitated a profoundly different church from the one the disciples imagined after Pentecost.

SECOND: We are not in a contemporary or temporary “exile.” Such language made sense to a generation that came to leadership in the 1970s, but for the generations that followed, this is not some strange exilic land. Exile language is tinged with the eventuality that there’s a way back. In truth, there is no returning, no going back. We are in a new location, a land many people call home, and so the churches must ask very different questions. Exile questions about how to fix and make the church work again won’t help us to discern the Spirit.

THIRD: This space of unraveling is a space of hope. We are witnessing the Spirit preparing us for a new chapter in the story of God’s mission. Our churches are at the end of a way of being God’s people and at the beginning of something significantly different. It involves our awakening to an invitation that is not about fixing the church but a journey of exploration.

FOURTH: In this journey we are experiencing dislocation. More than adjustment, major change is required. The Spirit’s invitation requires risk-taking, as we try on practices that will seem strange and awkward at first. It will ask us to change our basic sense of where God is at work. It will change our ideas about the location of God’s actions.

FIFTH: We are embarking on a shared journey to discern what the Spirit is up to ahead of us in our neighborhoods and to join God in these places. How do we discern together? How do we join with God? How will this joining require us to be changed as a gathered people?

SIXTH: Like all new journeys we will need new ways of traveling. For Christians these ways are called practices. The final chapters of this book will explore several of them.

For these six reasons and lots more, I think the unraveling is God’s good news for us. This is not the first time the Spirit has substantially disrupted the established patterns of the church’s practice and place in a culture, and it will not be the last. Old Testament and New Testament examples abound. In addition, think of the disruption that happened when Christianity was formally designated the official religion of the Roman Empire—that dislocation led to the initiation of a rich desert monastic tradition. By the fifth and sixth centuries, Europe was in a period of massive social dislocation, and it sparked the emergence of new movements like the Celtic missionaries of the British I...