Part I The Foundation—Conversational Competence

Urban Luck Design, urbanluckdesign.com

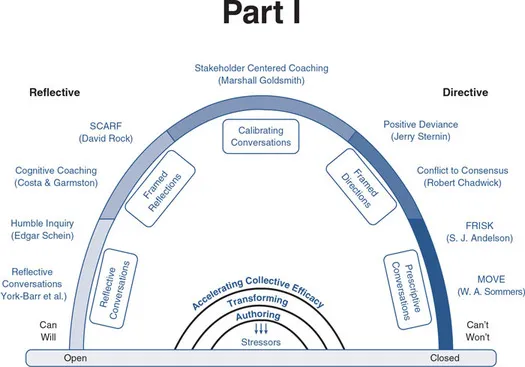

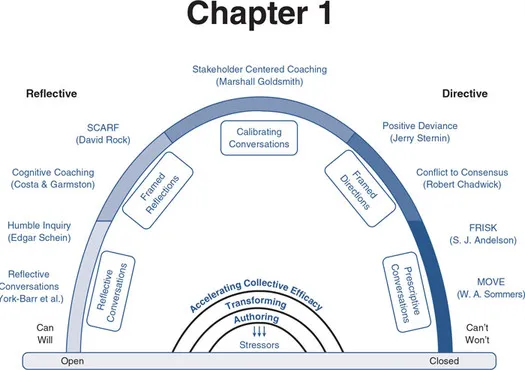

Take a few minutes and study the Professional Conversation Arc, which depicts the Nine Professional Conversations to Change Our Schools. What can you learn about this book from the diagram? Which conversations or practitioners do you already know? Which ones are new to you? For those conversations of which you are familiar, how do they relate to each other and their placement on the arc? What are you most curious to learn about?

Part I sets a context for why conversations are valuable and essential for building collective efficacy; conversations are the glue that builds cultures. While this section could be skipped in favor of going directly to the Nine Conversations, we believe it offers some important insights about why this book is so important.

Before delving more into the specifics of the graphic, we realize that we need to explain why these kinds of conversations are essential for the profession. To us, it seems obvious; to others, however, it is not so obvious. The lack of understanding about the need for professional conversations by educators, leaders, and teachers alike has been puzzling to us.

This dilemma is best told through a story. A principal new to a school offered his teachers release time to work on curricular issues. Their response was, “We do not know what we would do with the time.” He was shocked. When he was a teacher, his school had used school improvement funds to buy three days of collaboration for every grade level. That time was like gold to the teachers. The agendas were teacher directed, and some even stretched the three days into six half days. They had used it to bring their curriculum into alignment, to plan together, and to learn from each other. He knew he was a much better teacher as a result of this collaboration. This principal realized he had his work cut out for him. His teachers obviously had not done much collaborative work (indeed, the school was known for its rugged individualists).

In these next three chapters, we describe why educators everywhere would be well served to add a new knowledge domain to their practices: the skill and art of the conversation for expanding professional practices. As teachers, many intuitively understand how important language is for learning but do not actively pursue ways of improving these skills in their own professional practices. Instead, they fall back on what they know, what has served them in the past, and what is needed for the situation at hand.

In Chapter 1, we argue that conversations create bridges to understanding that open up access to knowledge coherence. By knowledge coherence, we mean that teachers seek agreement about what is essential for teaching and learning. When they don’t agree, they agree to work toward coherence and clarity about the nexus of their philosophical disagreements. Coherence does not infer agreement, but rather an understanding of the whole—the agreements, the points of divergence, and the impact of disagreements on learning.

It is only when professionals know what they stand for, can articulate how they make a difference for students, and are willing to question each other to find central truths that they can create a professional narrative of excellence.

When teachers join together and learn to articulate about shared practices, they communicate what is important to their students and to the community. They stand tall, firm in the respect given them as professionals. When this happens, they have created a knowledge legacy, which passes this professional knowledge onto newcomers.

In Chapter 2, we explore the problems created by the knowing–doing gap often reinforced by the lack of meaningful collaboration. Quite frankly, the current preservice programs are not sufficient for a 21st century profession. For this reason, schools must step in and assure that teachers become lifelong learners. The only way that this happens is through collaborative conversations.

In Chapter 3, we focus on the problems that arise in cultures that do not work well together and describe four stress reactions that block open, honest communication. We draw from adult learning theory to demonstrate how these dysfunctional communications can impede the goals of collective efficacy—the ability to author a future and to transform our thinking in the light of new data.

Together, these three chapters address this thesis: Professional conversations are essential for professional learning by describing what, why, and how these conversations fit into the context of professional learning communities. To better understand the intention of this book, take a minute before you begin Chapter 1 to review the graphic on the opposite page one more time to get a sense of the long-term outcomes of this book.

1 A Crisis in Our Midst—No Coherent Knowledge Base

Urban Luck Design, urbanluckdesign.com

Organizations are made of conversations.

—Ernesto Gore

In our profession, a simmering crisis has been building, yet most educators do not even know what the crisis is and how dire the situation has become. The crisis is that, as a profession, education has no coherent knowledge base about standards for excellence. Paraphrasing from Hargreaves and O’Connor (2018), professional collaboration is about creating this deeper understanding, which advances our knowledge, skills, and commitment to increase learning.

Over the course of a career, teachers develop deep knowledge about how to support the learning process and student growth and development. Yet these insights are rarely shared within the larger community of professionals. Instead, educational methods cycle from one new program to the next, with little attention to how professional knowledge is developed and shaped to create a communal understanding. The end result is that educators have no control over their professional narrative or the standards used to measure excellence. There are historical reasons why other professions have not experienced the political whipsaw so prevalent in education, and educators would be well served to pay attention to this history.

Knowledge Coherence Grows Knowledge Legacies

Over the past 100 years, other professions have amassed what have become large knowledge legacies—essential bodies of knowledge that were developed through coherence over time, disseminated through printed tomes, and used to ground conversations. With the advent of the digital age, this knowledge has become accessible in ways once not thought possible. Most notably, lawyers have case law and sources such as Westlaw; doctors have the National Library of Medicine now digitized as Medline; and accountants have Financial and Government Accounting Standards. Science has basic research standards and a growing body of “consensus standards” in the subspecialties. These knowledge bases are additive and adaptive as they continue to grow and change with the profession. Over time, professions that take the time to find coherent patterns, which include debated topics, can speak with an authentic voice; by doing so, they maintain a level of professional integrity that educators can only dream about. As Hargreaves and O’Connor (2017, p. 1) state, “No profession can serve people effectively if its members do not share and exchange knowledge about their expertise or about their clients, patients, or students they have in common.” There is no question that knowledge builds capacity over time as it is passed from generation to generation.

In education, the status quo has hidden behind the idea that teaching is more art than science and hence, like art, difficult to quantify. Teachers often cheer when assured, “You are the professional; do your best work.” What is not stated is that this “best work” is more often done in isolation, and it is a rare school that has figured out how to capitalize on this vast storehouse of applied knowledge. A wise administrator once ruefully commented that when a teacher retires all that knowledge goes with them to the grave. There is an African proverb that sums this up: “When an old person dies, a library burns.” We would add—what an unnecessary waste.

In large part, this historical failure to develop a knowledge coherence is because education is a human endeavor—learning appears to be as unique as fingerprints—making it difficult to find patterns, definitive solutions, or even agreement on basic tenants. Hence, as a profession, teaching has been controlled, even whipsawed, by outside political forces. When national debates further divide the community, as they did in the 1990s with the “curriculum wars” (and are now happening with the Common Core State Standards, or CCSS), the decisions are tossed back to local schools, which often have no understanding of the initiating beliefs or even what is being debated. These debates have a way of polarizing groups and developing contempt before investigation. These words may seem strong, yet they speak to a troubling truth. Teachers, and the parents in support of these teachers, line up to advocate for what they already know, and in the heat of the moment, all conversation is lost. In the void, governing bodies rush to simple solutions, failing to examine the underlying beliefs and assumptions.

For example, in the 1990s one school board in a university town ended conflicts by adopting two different algebra books: If you lived on the east side of town, you received one curriculum; if you lived on the west side, another. While this town was committed to democratic practices, they could not find a way through the conflict that arose around two different textbooks.

These kinds of compromises are not uncommon when communities do not have the conversational tools to open up deep understandings; as a consequence, decisions get made from a limited perspective in order to stop the conflict. This conflict avoidance serves to deepen the unspoken divides and creates crises fueled by ignorance. And most damaging of all, this glossing over of the real truths exhausts those involved in the implementation and confuses parents and students. Instead of an opportunity for professional learning, those involved tend to become even more defensive. No wonder so many teachers are leaving or plan to leave the profession as soon as possible.

An example of a better way to make policy would be to ask the educators in conflict to reconvene, possibly with someone skilled in professional conversations, to identify the similarities and differences between these two different approaches. Any one of the Nine Professional Conversations in this book could be used to open up a dialogue about these differences. The key is that agreement is not what is sought, but rather a coherence, which means that ideally the professionals will work to find overlapping understandings and to clarify points of disagreement. Just as in successful interest-based collective bargaining, when professionals can “agree to disagree” they can then move to more productive conversations. Furthermore, these debates about textbooks and programs distract from the real issues confronting educators, which is the development of a coherent understanding of teaching and learning beyond these prescriptions to what really works in the classroom.

Another example comes from the drama that has played out in the current debates about the Common Core State Standards (CCSS) that were initiated by politicians to create an internationally competitive education system. One year, teachers work hard to implement the CCSS, only to find that their state has repealed these same standards in subsequent legislative sessions. This policy whipsaw leaves teachers without direction and further undermines any desire to work toward a common understanding—the genesis of knowledge coherence. As one teacher put it, “All the public debate about standards makes me want to go back in my classroom and shut the door on the world.” Meanwhile, the politicians, distracted by a polarizing debate, have ignored some of the best practices from a growing body of knowledge about what makes other countries’ educational systems successful. Policy makers would be well advised to pay attention to the rest of the world. (For more information, see Surpassing Shanghai [Tucker, 2012]; Finnish Lessons 2.0 [Sahlberg, 2015]; The Flat World and Education [Darling-Hammond, 2010]; and Cleverlands [Crehan, 2017].)

Teachers Voice the Need for Knowledge Coherence

Wise teachers articulate the desire for conversation and want to become more expert, yet their voices are drowned out in all the rhetoric about failing schools. Sarah Brown Wessling, 2010 Teacher of the Year, said, “When I look at the standards, I don’t see a document that tells me what to teach or gives me a curriculum; rather, I see an underlying organization that gives us collective purpose.” Another teacher from a charter school, Darren Burris (2013), remarked, “To me, the Common Core represents an empowering opportunity for teachers to collaborate, exchange best practices, and share differing curricula—because a common set of standards is not the same thing as a common curriculum.” There is a huge distinction between consultants telling teachers about the standards and teachers spending quality time digging deeply into the assumptions, beliefs, and strategies as part and parcel of implementation. Leaders must find creative ways to engage teachers in meaningful conversations about the changes they wish to make. Conversations matter for the implementation of any curriculum.

Well-articulated conversations open up knowledge coherence and help peers understand their differences in order to foster the development ...