![]()

PART ONE

CONTEXTS FOR LEADERSHIP DEVELOPMENT

INTRODUCTION

This part of the book is about contexts for leadership development. Any development process will take place in layers of context. For instance, it may be that the process of leadership development is created in a large global company, which provides an organisational context. And the context may be a particular sector such as business or the public sector. It may be a particular country or a whole geographical region. Our overriding point is that leading occurs within nested contexts and that therefore leadership development needs to accommodate these. However, especially in texts from the United States, there is a tendency to write generally about leadership as though there is some universal process which merely requires some simple modification to suit the organisation or the social setting or anything else that is the context for development. In this part, therefore, we have shown the implications of working in particular contexts.

What we are not saying is that there are no lessons that can be taken from one context into another. However, what is necessary is for the developer to be aware that you are moving from one context to another and that has to be taken into consideration in the design of any development programmes or processes. In a globalised world there are inevitable overlaps across contexts. International companies contain leaders of different nationalities. The work of Gert Hofstede (1980) has been built on over the years to show that national cultures impact hugely on working practices. International leaders have to be sensitive to the different cultures that their staff come from.

Learning about other cultures is therefore important. However, it has to be the right kind of learning. Research from people like Ratiu (1987) has shown that leaders who move from one national culture to another are best to focus on having loose hypotheses about the new culture such that they use their learning capabilities to modify and enrich such tentative hypotheses as they go along. Leaders who are less effective either have a relatively rigid model of the new culture, which they fail to modify through time (i.e. they are poor learners) or they have no hypothesis to test and are therefore at sea in the new culture. The phenomenon of ‘culture shock’ is common among such leaders. All of this implies the need for leaders to approach new situations with a learning orientation.

The research on national cultures is relevant also, for instance, where leaders are moving from one company to another. The same need for continual learning is necessary – and the ability to test and refine hypotheses is crucial. In this part, then, we show how context is a crucial determinant of development processes.

THE CHAPTERS

The first two chapters focus on the country as a context. Both Hungary and South Africa feature here. Both countries went through significant change at the end of the last century (and are still adjusting to those changes). Hungary moved from a socialist, centralised, planned economy part of the Warsaw Pact into an independent democratic country. South Africa moved from the apartheid era into a democratic country. In both cases there were major errors made by visiting consultants, especially from the USA and the UK, in assuming that they could bring the lessons from these and other countries into the contexts of two countries that had been through major change. Clearly both countries needed support for change but not the kind that was often offered to them.

It is not that the kinds of decisions made in those countries cannot be transferred to other countries. Rather, the value of these two chapters is to have to use a particular lens in looking at changes that they have been through and what that means for development processes. Magdolna Csath focusses on the issues for a particular region – Central and Eastern Europe – from the perspective of a Hungarian while Chris van Wyk emphasises the issues in South Africa that are thrown up by its multicultural context.

The next two chapters focus on sectors as a context for learning and development. In the chapter on converging spheres, the focus is on the notion of particular spheres that overlap within a national context. Tony Eccles demonstrates how the overlapping contexts in a socioeconomic setting need to be a context for leadership development. The following chapter from Brian Findsen focusses on one particular context, namely that of higher education. The university sector produces particular issues in addressing leadership development.

Shilpa Kabra Maheshwari places her focus on exploring what she describes as the ‘contextual enablers’ within organisations themselves, providing a rich and recent insight into how to think about in-house programmes. The last chapter in this part is about groups. Groups are subsections of an organisational context and provide an important context for learning and development. Michael Reynolds draws on the use of group work as a basis for development.

CONCLUSION

Clearly, we have not tried to be encyclopaedic and attempt to cover every imaginable context for the activities of leaders. It is apparent, for instance, that other regions of the world have their own issues about leadership development. There are other sectors that could be mentioned such as NGOs and charities. Also, indigenous people emphasise how their approach to leadership development is different (especially as training courses have been relatively unknown).

Our aim has been to provide a rich menu for the reader to use with the intent to highlight that these layers of context are always present and should be uppermost in the minds of developers.

REFERENCES

Hofstede, G. (1980). Culture’s consequences: International differences in work-related values. London: Sage.

Ratiu, I. (Ed.). (1987). Multicultural management development. Special issue. Journal of Management Development, 6(3).

![]()

LEADERSHIP DEVELOPMENT: EXAMPLES FROM CENTRAL AND EASTERN EUROPE

MAGDOLNA CSATH

We cannot solve our problems with the same thinking we used when we created them.

Albert Einstein

INTRODUCTION

Based on the voluminous available literature we can conclude that leadership is a complex concept. It cannot be simplified to creating economic value for shareholders. It also has to be responsible for creating value for society, for all stakeholders, including employees and communities. But how can these required new leadership skills be acquired? How can educators reflect on these new requirements? Can traditional business schools play any role in equipping leaders with the necessary skills?

THE ROLE AND OPPORTUNITIES OF LEADERSHIP DEVELOPMENT

Traditional business schools have been concentrating on developing very efficient managers who are able to produce great value for shareholders at the lowest possible costs. They have strongly emphasised the so-called ‘hard’ subjects like marketing, competition strategy, accounting and so on. The methods used have been mainly individual learning based on competitive performance. The role of business in society, ethical issues and cooperation has not even been mentioned. We could describe this type of education as the ‘antithesis’ of leadership development. Teaching and development are different things. One can easily learn hard, economic subjects, but soft skills are tacit, they need good examples, role models and an encouraging environment in order to achieve development.

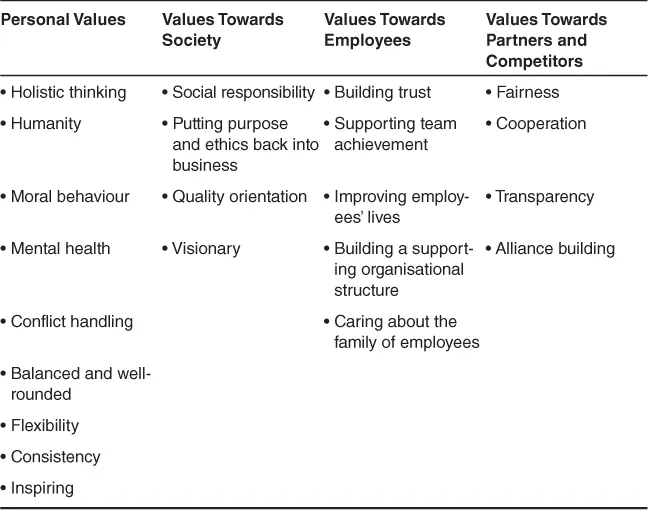

In Table 4.1 there is a summary of the research findings on the special values and soft skills needed for a good leader.

But is it possible to teach soft, human and ethical skills in a business school at all? My Hungarian sample proves that these traits first of all come from family values, early education and the effects of society combined. Great role models may also shape leadership values, especially in the case of young people who have the chance of working together with great personalities who mentor their younger colleagues. Learning, as Cunningham (2021) points out, should be a continuous and cooperative process. I believe that soft skills are becoming more important, but the contradiction is that they cannot be learned in a formal educational setting. To acquire them is a socialisation process. This leads us to the question of the roots and shapers of leadership in Eastern Europe, where political changes have left a mark on leadership values and skills.

Table 4.1. Leadership Values and Soft Skills.

WHAT SKILLS WERE LEADERS REQUIRED TO HAVE AND HOW DID THEY ACQUIRE THEM IN EASTERN EUROPE?

I worked in an education centre in the early 1980s when the so-called ‘socialist system’ had already loosened its grip on society. At that time this was the only management education centre in Hungary. This situation was typical in the region: one management education centre tightly controlled by the party was allowed to offer courses to the managers of the so-called ‘socialist companies’. I emphasise ‘manager’, as the word ‘leader’ was used exclusively for the party bosses. As a young economist, I was allowed to teach a few so-called ‘capitalist subjects’, like strategic management.

Our course participants came from companies, but it was not voluntary to enroll. They were sent by the supervising ministries or party officials. Of course, nobody knew what ethical and social values were ingrained in these people as individual values as, at least on the surface, they had to be overshadowed by the imposed ‘socialist values’. In the case of company managers these values covered the so-called three basic socialist requirements: political reliability, human quality and management (not leadership!) knowledge. At that time businesses, in practice, consisted of the combination of three sub-organisations: the economic production part of the organisation, the local communist party representatives and the local organisation of the single existing trade union.

An analysis from Héthy and Makó (1979) summarised the leadership problems in the following way:

companies operate ineffectively because the selection of leaders is not based on leadership skills. Motivation is at a low level, the tasks, rights and responsibilities are not allocated properly and logically in the organisation, it is not clear who is responsible for what. Lack of coordination, disorganisation and anarchical tendencies characterise business organisations.

The problems of leadership education were reflected in the curriculum and the teachers. The majority of the subjects were related to the operating mechanism of the socialist state and the communist party. Most of the lecturers came from the ministries and the party headquarters. I myself had to fight for the inclusion of at least a few typical ‘Western types of management subjects’, like strategy, organisations, human resources management and so on, into the curriculum. I actually lost my position after a while because I was accused of ‘importing capitalist ideology’ and by doing so harming the socialist way of teaching socialist leaders. After these charges I was unable to find a job, so I had to leave the country because at that time not having a job was considered to be a crime.

After the so-called ‘system change’ in 1990, suddenly everybody wanted to become a great capitalist. Foreign business schools moved to the region offering the typical American style business school curriculum with American cases. This was sufficient for the Western businesses buying into local companies as they did not want to hire local leaders. They needed local managers who implemented the goals of the foreign owners. Foreign owners of course wanted a very simple thing: the highest profit as soon as possible at the lowest possible cost. This meant that local managers had one task: to get the most out of the local employees. Because the unemployment rate – based on the IMF data – jumped from 2% in 1990 to 11.3% by 1993, employees had no choice but to accept the harsh, inhumane employment conditions. Of course, those who did not want to be employed in such conditions tried to set up small businesses. Some of these businesses are still around. These people did not have any formal management education. The majority of them came from an engineering background and had worked in middle-level positions in the earlier socialist enterprises. Some of them failed, as they did not know how to build a viable business organisation and others are now in the position of handing the business over to their children, who are already not only specialists in one field or another but may also have been able to acquire some leadership education locally or abroad. Their leadership style is shaped by what they have seen over the years in the family business, by their formal education and by the societal and political environment around them. In practice, however, it does not seem to be easy to convince the children to take over the business. The reasons generally given are related to the business environment which is – as mentioned in all major competitiveness reports – not friendly for the local small businesses.

I will now summarise the conclusions of a survey I carried out with a group of acting leaders from different economic branches and company sizes.

WHAT DO BUSINESS LEADERS THINK ABOUT LEADERSHIP AND LEADERSHIP DEVELOPMENT IN HUNGARY?

Based on the different approaches to leadership skills and practices described so far, it is now worth demonstrating a few real-life examples. I asked eight top executives in businesses of different sizes and from different industrial branches to answer six questions related to leadership issues. I was pleasantly surprised to learn that they were all very pleased with the exercise. The CEO of the largest company in the sample said that the questions had helped him to reflect on issues that he had never thought of. I quote: ‘Thank you for the opportunity to reflect on some circumstances, and even on myself, in a way that I haven’t done before’.

They all answered the same six questions:

1. In your opinion, what is the difference between a leader and a manager?

2. Have you completed any leadership/management courses and if so...