![]()

Part One

Hearing Race and Place

![]()

1

Mapping Sonic and Affective Geographies in Richmond, Virginia

Andrew McGraw

Introduction

Richmond, the historic capital of the Confederacy, has a post-civil-war history pockmarked by racist housing policies and attempts to extend Jim Crow laws. The strategies employed include “redlining” (grading property values according to race) and using public housing projects and school district gerrymandering to further segregate populations. In the 1930s, Virginia’s “racial integrity laws” prohibited interracial marriage and were used to segregate neighborhoods by disallowing people from living in an area whose residents they could not marry—policies borrowed by the Nazis when they developed their own Aryan purity laws (Campbell 2011: 144). The 1968 Fair Housing Act, which opened some areas to non-white populations, accelerated “white flight” out of the city toward the south and west, further depleting Richmond’s tax base. As demonstrated through the AudibleRVA project (McGraw 2020b), a digital humanities project established at the University of Richmond, the sonic and affective aftermath of these and other racist policies are mapped onto Richmond’s present-day geography.

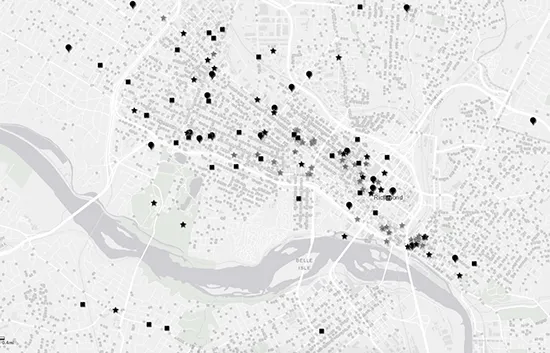

Begun in 2013, the AudibleRVA project combines multiple ArcGIS map layers outlining relationships between sound and the affective experience of place. Layers include noise complaints and citations, music venues and events, ethnographies, an archive of music made in the city jail, and student soundscape points and research projects (Figure 1.1). At the heart of the project is the recognition that all mapping is political and that all visual representations of data tell stories reflecting particular research questions and positioned perspectives (Tufte 2001: 53; Droumeva 2017: 337).

Figure 1.1 AudibleRVA map with several layers displayed. Gray dots = noise complaints; black stars = active venues; gray stars = defunct venues; black pins = ethnographic interviews; black squares = music infrastructure (music schools, stores, studios).

In this chapter, I interpret quantitative and qualitative data from AudibleRVA to explain the acoustic politics of space in Richmond, illustrating the differential distribution of sonic rights and resources. The project’s core assumption is that a society’s ethical life (Keane 2015: 6) is partly expressed through the allocation of sonic “goods,” including access to music-making and listening and musical infrastructure (venues, schools, stores). How does access to such sonic goods—and the right to make and be free from “noise”—express and reproduce a society’s political theory and ethics? Whose sounds are muted? These questions of justice, equity, and distribution have been central themes in Western moral theory since Aristotle’s Nichomachean Ethics (Ross 2009). My project’s analytic focus does not concern normative definitions of noise, sound, or music but rather what we might call opportunities for sonic eudaimonia, Aristotle’s term for “flourishing” and the goal of his ethics. Who in Richmond is extended the opportunity to flourish through sound, and how is sound policed to restrict flourishing?

Sound is a modality through which a public organizes itself—a means of expressing inclusion and exclusion, marking territory and constituting normative citizenship. The discontinuous topography of the AudibleRVA map layers resonates with theories of modern publics as a collection of disjunct and overlapping “affective societies” (Slaby and von Scheve 2019: 1), often with distinct sonic cultures and value systems. Within this context the AudibleRVA map leads to another question: What role might sound and music play in forging new, more inclusive affective publics, enabling broader access to the common good? This chapter focuses on the intersections of class and race in Richmond, primarily in terms of the binaries between perceived Blackness and whiteness, historically the most salient social divide in the city. Since the geographies mapped in this chapter include many other growing populations of marginalized groups (primarily Hispanic and Asian), the discussion below should be understood as only one of many possible ways to analyze the intersections of identity, class, place, and the law in Richmond.

Affect and Sound

In attempting to understand the meaning of Richmond’s soundscape, I have conceived of it as an assemblage of interactions between affective and sonic fields (McGraw forthcoming). I understand a field as an enabling condition of a situation that has concrete effects by orienting phenomena around its lines of force. Fields are not inner, mental worlds accessible to one person only. They are immanent-real, not simply a property or quality of a situation. The sonic field comprises vibrating pressure differentials in a media, including vibrations below and above human-cochlear hearing and at all possible amplitudes. It encompasses all modes of vibration—music, sound, noise, silence—including vibrations within auditory systems (nerves, guts, bones) and across transductive thresholds.

The affective field is subtler. Despite considerable disciplinary schisms over the meaning of affect, I think theorists can agree that we experience more than we explicitly represent to ourselves. In my usage, affect is meaningful feeling in a situation, diffuse and discursive, below, within, and beyond language. Recent phenomenological and materialist attempts to describe the affective experience of sound in a space by enumerating all of the substance, apprehensions, discursive systems, and networks measurable within it never seem to produce a complete description. This, I argue, is because affective experience is partly conditioned by the probability space of a situation, which is established by presence and absence, possibility and constraint, things you can measure and things you cannot. Our affective experience of a situation emerges from a sense of what has happened, is happening, and what will (or will not) probably happen within it. In Richmond, understanding the experience of place as interactions between affective and sonic fields helps us recognize the city’s “sonic color lines” (Stoever 2016: 1).

Noise

In his canonical text on noise and society, Attali says:

It is necessary to ban subversive noise because it betokens demands for cultural autonomy, support for differences or marginality: a concern for maintaining tonalism, the primacy of melody, a distrust of new languages, codes, or instruments, a refusal of the abnormal—these characteristics are common to all regimes of that nature. They are direct translations of the political importance of cultural repression and noise control.

(2003: 7)

In this section I outline how “noise,” in its various guises, is associated with African American life in Richmond and is policed for its perceived link to subversive and criminal behaviors. I facilitate a music studio program in the city jail, the population of which is 92 percent African American in a city where the Black population is 50 percent. The styles of hip hop preferred by Black male residents in the program are sometimes referred to as “noise” by the overwhelmingly African American staff, who encourage participants not to produce “thug” or “street” music, but instead to create “uplifting” and “positive” tracks that concern “the struggle” or “recovery.” Staff expressed concern to me that “rough” music “leaking out” of the jail would reinforce racist stereotypes associating Black men with inherent criminality.1 As I describe below, the policing of Black “noise” extends beyond the jail walls, segregating the city’s geography through discontinuous soundscapes.

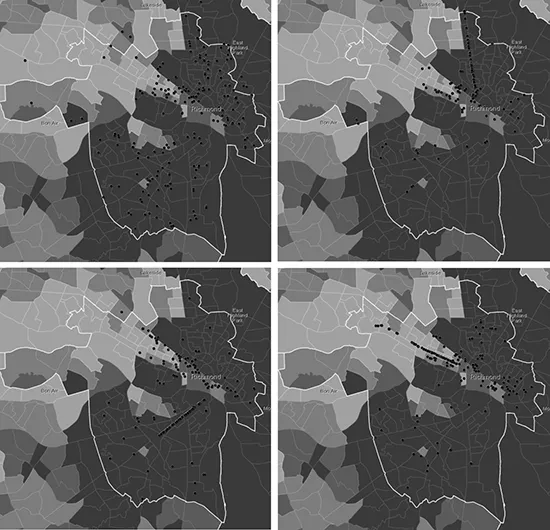

Noise ordinances in American cities have long been associated with both class and race. “Street” music was a regular target of early (nineteenth-century) noise ordinances, partly as a means to legitimate the ticketed music being programmed in new concert halls (Schafer 1977: 66).2 Noise complaints in contemporary Richmond align similarly. Figure 1.2 illustrates the AudibleRVA noise layer, which records the roughly 40,000 noise complaints registered by the police between 2007 and 2019.3 This information was obtained through a Freedom of Information Act request to the Richmond police department. This map layer outlines the sonic dimensions of racialized surveillance and privilege more than it does the distribution of objective noise levels in the city. As the map confirms, the city’s ordinances disproportionately affect the acoustic practices of African Americans. The panes of Figure 1.3 illustrate a marked transformation in complaint patterns in Richmond before and after 2011, when a restrictive noise ordinance was passed.4 This controversial new ordinance defines “excessive sound” as that which “exceeds 55 dBA during nighttime hours and sound that exceeds 65 dBA during daytime hours when measured inside a structure, or sound that exceeds 65 dBA during nighttime hours and sound that exceeds 75 dBA during daytime hours when measured outside a structure, or both” (Richmond City Government 2016). For context, 65 dBA is roughly equivalent to the volume of everyday conversation. Any individual or business responsible for excessive sound may be issued a citation.5 That only thirty-three citations resulted from the 40,153 complaints registered between 2007 and 2019 suggests that the noise ordinance functions as a proxy for other forms of racialized surveillance and punishment through uneven and targeted enforcement.6

Figure 1.2 Black population density/noise complaints 2007–2019. Black population density indicated by shading.

Such enforcement is exemplified in Figure 1.3, where the “scatter plot” pattern of noise complaints registered prior to the passage of the ordinance indicated in panel A transforms into the highly patterned strings of complaints registered in panels B, C, and D. The complaints in A track Chamberlayne Avenue through an African American neighborhood, while those in panel B track along Jefferson Davis Highway through Black neighborhoods south of the James River. Complaints are also evident within and bordering the primarily white “Fan District” in the middle of the city, shown in panel D.

Figure 1.3a–d Typical noise complaint patterns before and after passage of restrictive noise ordinance. (a) Top left: June–July 2010, “scatter plot” pattern. (b) Top right: November–December 2011, complaints registered along Chamberlayne Avenue. (c) Bottom left. August–September 2012, complaints registered along Jefferson Davis Highway. (d) Bottom right. May–June 2013, complaints bordering and within the Fan (center of map).

Some jail residents have stated that their arrest was tied to a noise complaint. When police respond, they may run names in their database to find outstanding warrants or arrest individuals for other offenses such as minor drug possession. In this context Black “noise” becomes a proxy for punitive racialized surveillance. Given Richmond’s cultural and social history, Blackness—especially Black masculinity—is strongly associated with noise. Indeed, the ordinance seems to single out this group based on stereotypes about their listening habits. Anyone playing music via a “loudspeaker” in their car must obtain a permit from the city—language that ostensibly regulates businesses such as ice-cream trucks. But in practice, the ordinance represents a means to control the widespread African American cultural practice of installing powerful car stereo systems. Based on my own observations living in a multiracial (40 percent African American) neighborhood in the city, hip hop is the primary genre played through car stereo systems, and it accounts for 90 percent of the music produced in the jail studio program.

The preference for strong bass over Western “tonalism”—evident in the genres of rap preferred by this community, and the practice of accentuating it further with powerful subwoofers—is precisely the “demand for cultural autonomy” Attali describes. Low frequencies can engulf a space with diffuse energy, making it difficult to locate their source; they can seem to come from everywhere at once. When originating from mobile audio systems playing “noisy” rap, this sonic “invasion” of a territory can prick panic in neighborhoods historically zoned as white. The fact that much urban sound exceeds the ordinance’s very low threshold enables officers to instruct those who do not “know their place,” to “move along” (to quote a resident of the city jail) if they are thought to be outside of their proper territories. While in many American cities, race is both an auditory construction and a bodily orientation in space (Ahmed 2007: 158), identity in Richmond, as Figure 1.3 illustrates, can be defined partly by inhabiting a certain sonic field.

The experiences of...