eBook - ePub

Woodturning

A Manual of Techniques

Hugh O'Neill

This is a test

Compartir libro

- 192 páginas

- English

- ePUB (apto para móviles)

- Disponible en iOS y Android

eBook - ePub

Woodturning

A Manual of Techniques

Hugh O'Neill

Detalles del libro

Vista previa del libro

Índice

Citas

Información del libro

This is a comprehensive guide to woodturning which will be of value and help to both new and experienced woodturners.Hugh 0'Neill covers the tools and woods used in turning, the principles of design, the lathe, wood finishing, and the techniques of turning spindles, bowls and decorative works. The book also covers the workshop and a selection of projects including bowls and table legs.

Preguntas frecuentes

¿Cómo cancelo mi suscripción?

¿Cómo descargo los libros?

Por el momento, todos nuestros libros ePub adaptables a dispositivos móviles se pueden descargar a través de la aplicación. La mayor parte de nuestros PDF también se puede descargar y ya estamos trabajando para que el resto también sea descargable. Obtén más información aquí.

¿En qué se diferencian los planes de precios?

Ambos planes te permiten acceder por completo a la biblioteca y a todas las funciones de Perlego. Las únicas diferencias son el precio y el período de suscripción: con el plan anual ahorrarás en torno a un 30 % en comparación con 12 meses de un plan mensual.

¿Qué es Perlego?

Somos un servicio de suscripción de libros de texto en línea que te permite acceder a toda una biblioteca en línea por menos de lo que cuesta un libro al mes. Con más de un millón de libros sobre más de 1000 categorías, ¡tenemos todo lo que necesitas! Obtén más información aquí.

¿Perlego ofrece la función de texto a voz?

Busca el símbolo de lectura en voz alta en tu próximo libro para ver si puedes escucharlo. La herramienta de lectura en voz alta lee el texto en voz alta por ti, resaltando el texto a medida que se lee. Puedes pausarla, acelerarla y ralentizarla. Obtén más información aquí.

¿Es Woodturning un PDF/ePUB en línea?

Sí, puedes acceder a Woodturning de Hugh O'Neill en formato PDF o ePUB, así como a otros libros populares de Technology & Engineering y Technical & Manufacturing Trades. Tenemos más de un millón de libros disponibles en nuestro catálogo para que explores.

Información

Categoría

Technology & EngineeringCategoría

Technical & Manufacturing Trades1 Getting Started

It is workshop time!

Yon will need a plane, a chisel, a mallet, a sharpening stone, a vice (or means of holding the wood), and some scraps of timber. A bit of old deal will do.

Start with the plane. Hopefully the cutting edge is a little dull from when the kid tried to smooth a bump off the concrete path. Set the blade to give a coarsish cut – the blade clearly showing below the shoe of the plane. Now take a cut along the grain of the piece of deal. With considerable effort you will produce a coarse, broken ‘shaving’. The ‘finished’ surface of the wood is torn, and fibres have split away. With the plane in this condition we won’t even try to make a pass across the end grain – it probably would not cut at all however hard you push.

Now give the iron a few rubs on the sharpening stone and then fix it back into the plane. This time set it fine – only the merest edge of the blade will be showing, In fact if it is set fine enough you will probably detect the blade edge more by feel than by sight. This time, as you make a pass along the wood, you will find that with very little effort you can produce a long, fine shaving and the surface of the wood will be smooth and polished.

Try also a pass across the end grain. You will not produce a shaving but rather fine ‘sawdust’. Unless the blade was super-sharp the cut face may be flat, but it is likely to be ‘pitted’ where each fibre of the grain has been torn away from the adjacent one. The corner may have broken away where the plane exited from the pass.

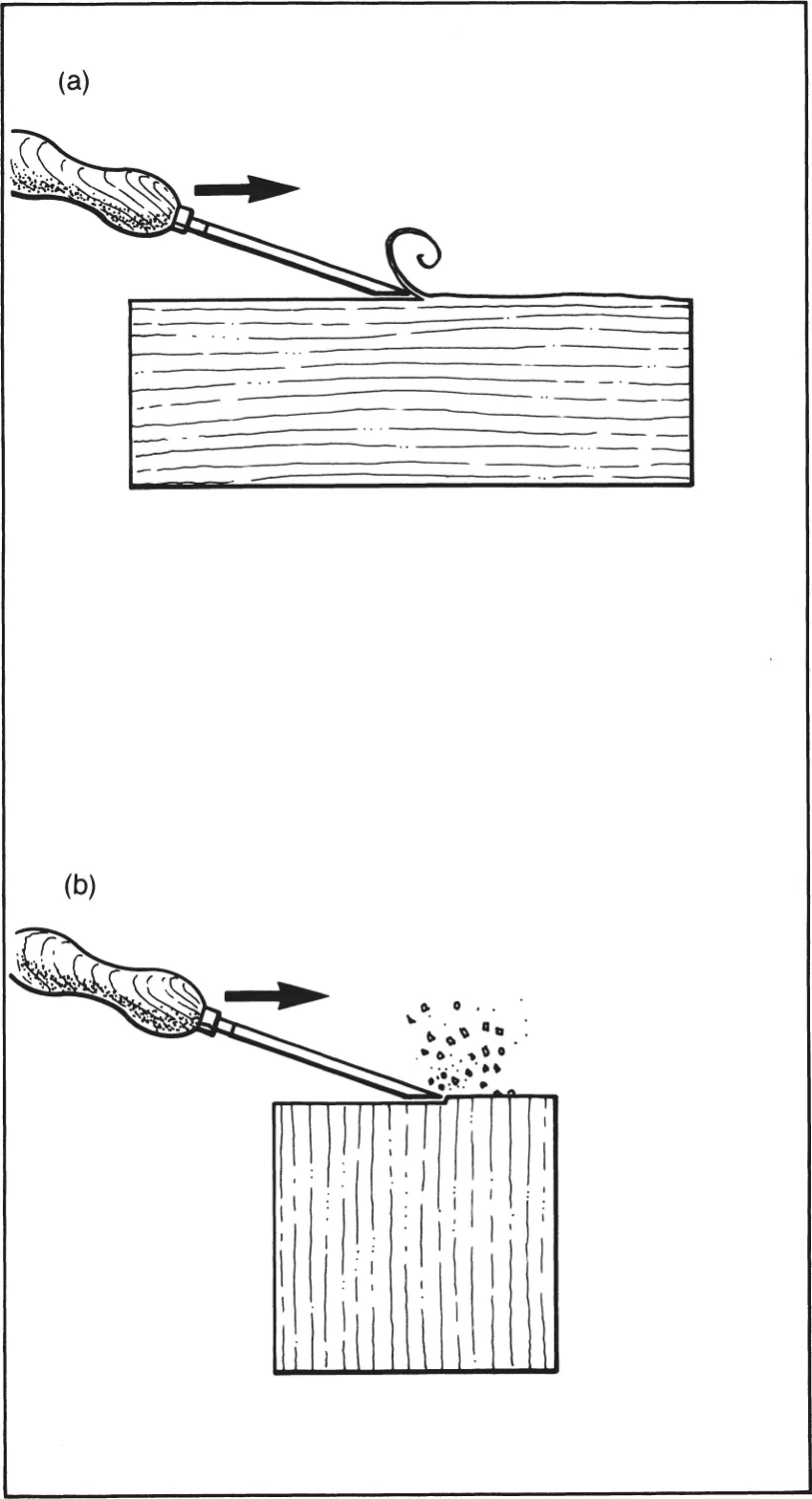

Cutting along and across grain. (a) Cutting along the grain, the chisel parts the long fibres from their neighbour. A flat bevel rubs on the cut timber and prevents the edge digging in deep. The result is a clean cut and fine shavings. (b) Working across the grain, the chisel slices off the ends of the grain which break away as ‘sawdust’.

Yes, of course, you can remember all that from your early days of woodworking – probably from school. Nevertheless try it again now and as you do so tell yourself:

‘One: blunt tools tear wood, and with the power and speed of a lathe the tearing is likely to be even greater than this.

Two: taking deep cuts also tears wood and requires much more effort.

Three: fine cuts are easy.

Four: fine cuts with sharp tools leave smooth finishes.

Five: a really fine planing cut with a sharp tool leaves a finish more “polished” than will the finest grade of sandpaper.’

And as you go off the edge on the end grain and the corner breaks away:

‘And six. Wood that is unsupported and is cut across the grain, parts along the fibres and tears away.’

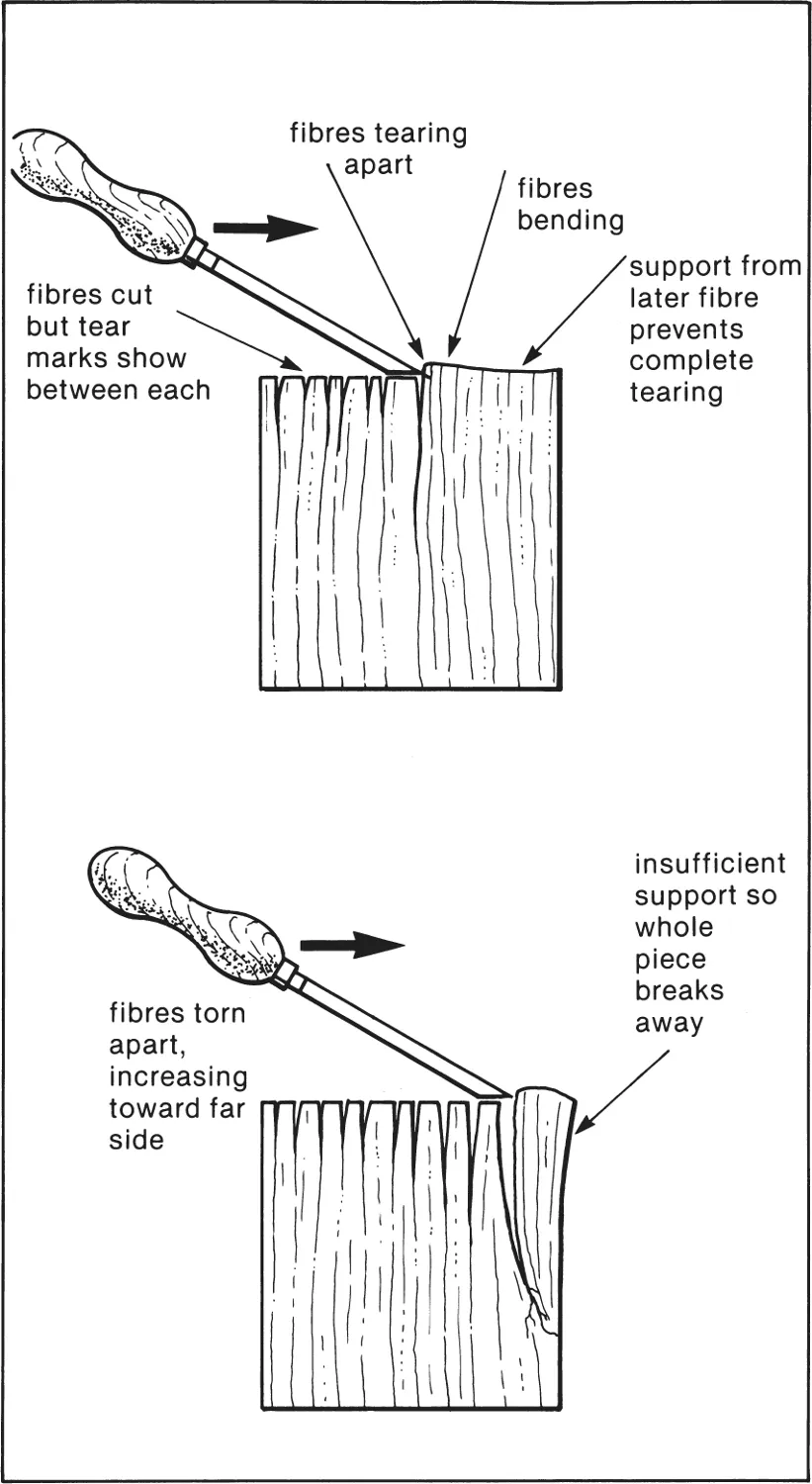

There is another little test that is worth doing to further illustrate this point. Take a clean paintbrush and stroke the ends of the bristles across the edge of a table. To start with, and through the middle of the stroke, the bristles will be bent back but will stay together as a mass. However as you get to the edge the remaining bristles will lodge on the table edge and will part right away from the mass. This is exactly what happens when you cut across end grain of a piece of wood. In fact it is worse. The fibres of the wood cannot bend as do the brush bristles; so they tear apart, break off, and leave the surface pitted.

In a nutshell what you have demonstrated for yourself is a substantial part of the theory of tool choice and tool control in woodturning.

Cutting end grain – even with a fairly sharp chisel.

Of course there is a difference between a plane (and a carpentry chisel), and the lathe and its tools. Indeed there are two fundamental differences. First, with the plane there is the body and shoe plate to prevent the blade digging in or taking too deep a cut. The second difference is that you move the plane and keep the wood fixed. In essence, with the lathe it is the other way around. You move the wood and keep the tool (and the lathe) still – or at least you try to!

So let’s see how we can emulate the plane when we are using tools without the assistance of the depth-controlling shoe plates. It is back to the workbench time!

This time use an ordinary chisel; you might as well start with it nice and sharp – we already know that ‘blunt tools tear wood’. Try two things. First rest the bevel of the chisel on the surface of the piece of wood. Now, holding the chisel handle firmly with one hand and with the finger and thumb of the other gripping and steadying the blade, push the tool along the surface of the wood. Keep the bevel flat and rubbing on the surface of the wood and you will not take off a shaving but you will polish or ‘burnish’ the surface.

Take another pass. This time raise the handle of the chisel the merest fraction until the edge starts to cut into the wood. Now you do take off a fine shaving but, providing you keep the bevel rubbing behind the cutting edge, you will still burnish the wood. The chisel glides easily along, and passes through the wood quickly. If it doesn’t then go and sharpen the tool!

The third pass is going to take much more effort. Increase the angle of the blade, push harder, and the chisel digs in, taking off a thick shaving and leaving a slightly rougher surface. The chisel pass was much slower. Too steep an angle or loss of control of the blade and you dig in and the pass stops.

Last exercise. Cut a small mortise into the wood – a rectangular hole. Keep the faces vertical. You will probably have to use a mallet. Note how the cut across the end grain leaves a clean polished face (if the chisel is sharp enough) whereas the cut made along the grain tends to break away long splinters. The chisel did not pass through the wood, but proceeded in a series of short jerks with each mallet blow.

So, what are the lessons here?

1 The chisel bevel should be kept in contact with the wood as it:

(a) Controls the depth of cut (just like the shoe of the plane).

(b) Leaves a clean cut and burnishes the surface of the wood.

2 Once the edge of the blade is unsupported by the bevel rubbing on the wood behind the cut, the edge digs in.

3 When cutting along the grain with a tool that is anything less than razor-sharp, then you tend to lift up and tear through the fibres rather than slice them.

4 In fine cuts the chisel moves much more quickly, whereas with coarser cuts chisel speed is lower and the effort required is greater.

Probably the only principle of turning that the exercises have not now demonstrated is that the corners of the edges of tools can catch on a rotating work piece and dig in.

If you always have these principles in mind, you will usually know what sort of tool to use to do different turning jobs. You can work out where to set the lathe tool rest, and even the speed at which the lathe should be run.

So let’s take our first look at the lathe. A few moments ago we saw that the difference between the plane and the lathe was that with the former the tool moved and the wood remained still, whereas with the lathe it is the opposite way round. It is both as simple as that, and yet as complicated.

The lathe takes the effort away – it moves the wood under power and (usually) in a predictable, ‘fixed’, rotary direction. As the lathe does the work, we can spend all our time, concentration and effort on controlling the tool. However you can stop a plane or a chisel in mid-cut – it is not so easy to stop a modern, high-power lathe in mid-rotation. Because it is moving the wood fairly fast, everything happens much faster. The merest slip with a tool edge can cause a disaster in milliseconds. There are stages in turning where the edge of the wood is only a blur – you have to make some guesses and go in boldly. Lathes are ‘decisive’ and they require decisive operators.

The biggest consideration of all is the obvious one. Lathes move the wood, but can only do so in a circular motion – so we can (broadly speaking) only produce round (or oval) objects with the lathe. So, while we think of chisels and planes as travelling in feet per second, we normally convert the feet per second of the wood passing the lathe tool into revolutions per minute of the lathe. What governs the choice of the speed of rotation that is used is still, effectively, the speed of the wood passing the tool tip as measured in feet per second.

There are optimum speeds of traverse of cutting tools across wood; and there are similarly optimum lathe speeds. As a basis, the rougher or coarser the work, the slower the speed we use. The finer the work the higher the speed. Within this framework we try to keep the speed of the wood past the tool fairly constant. This means one thing above all others – that the bigger the diameter of the wood we are turning the slower the speed of rotation that we have to use if we are to keep the rim speed (the spee...