![]()

CHAPTER 1

Early Days

Ironic as it may sound, it can be argued that the sequence of events that eventually led to the establishment of Waterloo station was initiated by the Napoleonic Wars. During that period (and indeed throughout the centuries preceding it) the swiftest route between London and strategic points on the south coast was waterborne, via the Thames and the Strait of Dover. Although Britain had secured naval dominance at the Battle of Trafalgar in 1805, the danger posed to vessels traversing the English Channel had never been more apparent, and it was clear that a more direct inland route – which would also avoid the perils of bad weather – would be hugely beneficial.

Canals Show the Way

With this in mind, moves were made to forge a canal linking London and the nation’s naval powerhouse, Portsmouth. Only two short sections of this grand vision came to fruition: the Wey & Arun Canal, which runs from Pallingham in West Sussex to Shalford, just south of Guildford; and the Portsmouth & Arundel Canal, a now filled-in waterway that cut across Portsea Island. Both of these networks missed out on serving their original purpose, having been completed shortly after Napoleon’s defeat at the Battle of Waterloo in 1815.

Map of Portsea Canal, 1815.

However, although the conflict with France was over, the idea of connecting the capital to Portsmouth via an inland course had taken hold, and a little further west along the coast, business leaders in Southampton were watching with a keen eye. Realizing the trade benefits that such a link would bring, they too began to plan for a similar canal, although it was soon realized that such a project would be far too costly.

Fortunately, a new and exciting mode of transport was beginning to make itself known in the north of England, demonstrated by the Stockton & Darlington Railway that opened in 1825, and the Liverpool & Manchester Railway that followed in 1830.

A Railway for London and Southampton

Quick to spot the potential of railway travel, a group of three men – all of whom had garnered a grim knowledge of business and shipping through their involvement with the slave trade – gathered on 6 October 1830 to draft a prospectus for a railway line connecting Southampton and London. This trio were politician and former army officer, Abel Rous Dottin (whose Southampton home, Bugle Hall, provided the venue for the meeting), Robert Johnston (who would later participate in the planning of the London & Greenwich Railway – the L&GW) and American-born Robert Shedden Jr.

In the early nineteenth century Southampton was a minor port. To give an idea of how some perceived the town at the time, we have this rather unflattering description from a history of the railway, published in the late Victorian era:

Due to these poor facilities, Dottin, Johnston and Shedden considered it would be advantageous to construct a modern network of docks and warehouses in Southampton as a means of encouraging freight for their prospective railway. To boost trade further, it was also anticipated that a branch line would be built, connecting Southampton to Bath and Bristol via Basingstoke.

These facets came together to create the company’s rather ponderous name, ‘The Southampton, London & Branch Railway & Dock Company’, which was formed in 1831. Clumsy title aside, the proposal proved popular. One newspaper at the time reported that:

Further support came when the company held its first public meeting at The London Tavern, Bishopsgate, at midday on 1 December 1831.

However, problems with the scheme soon began to appear. The dock construction aspect was deemed too expensive, whilst the Basingstoke branch brought the company into conflict with the Great Western Railway (GWR), who also had their sights set on Bristol.

It was decided therefore to shed these two elements and strip the project down to a straightforward connection between London and Southampton. This allowed for a much sharper name, ‘The London & Southampton Railway Company’ (L&SR), which was adopted in 1834 – and on 25 July of that same year, a parliamentary bill granted the enterprise royal assent.

The London Tavern

Despite sounding like a quaint pub, The London Tavern was in fact a grand banqueting hall where many important business gatherings were held. It was especially popular with burgeoning railway companies during the early nineteenth century. The establishment was noted for its turtle soup, and the cellar contained large water tanks in which the unfortunate creatures were kept. As we shall later see, Waterloo station played a major role in supplying London with this now taboo delicacy.

Construction

Having raised a budget of one million pounds, construction of the L&SR commenced in autumn 1834 under the direction of engineer Francis Giles. A protégé of John Rennie, Giles was already well acquainted with the route, having surveyed it during the period when it was envisioned as a canal.

A cautious and conscientious man, Giles was noted for a dispute he had engaged in with that other great railway engineer, George Stephenson, which had occurred during a committee examining the planning stages of the Liverpool & Manchester Railway. Giles had opposed the scheme, and noting that Stephenson intended to take the line across the boggy expanse of Chat Moss, declared that ‘no engineer in his senses would go through Chat Moss if he wanted to make a railroad from Liverpool to Manchester.’

Stephenson, of course, succeeded in proving this rather scathing remark wrong, and when it came to scrutinizing the route of the London to Southampton line, he had the opportunity to get his own back.

When the bill was being discussed in parliament, Stephenson’s expertise was called upon, giving him the opportunity to throw Giles’ words back at him in what was no doubt a satisfying retort: ‘No engineer in his senses would go through Basingstoke if he wanted to make a railway from London to Southampton.’ Stephenson twisted the knife further, predicting ‘the whole wealth of the company would be forever buried in the St George’s Hill cutting at Weybridge.’

Although he, too, was wrong about his opponent’s engineering knowhow, Stephenson was partially correct with regard to the project’s finances. Construction proved slow, and after two years Giles found himself well over his original budget, forcing him to increase the figure from £894,874 to £1,507,753 – over £197 million in today’s money.

Despite the project being in southern England, many of the shareholders hailed from Lancashire, and upon hearing of Giles’ revised estimate, these rather blunt fellows had him dismissed. They replaced Giles with Joseph Locke, who, in a meeting of shareholders at The London Tavern on 31 August 1837, provided a summary of the changes and savings he’d made. These included employing fellow railway engineer, Thomas Brassey – whom Locke described as a ‘very able and responsible contractor’ – to ‘execute all the remaining works from Wandsworth to the River Wey’, and by making contractors south of the Wey responsible for sourcing their own building materials.

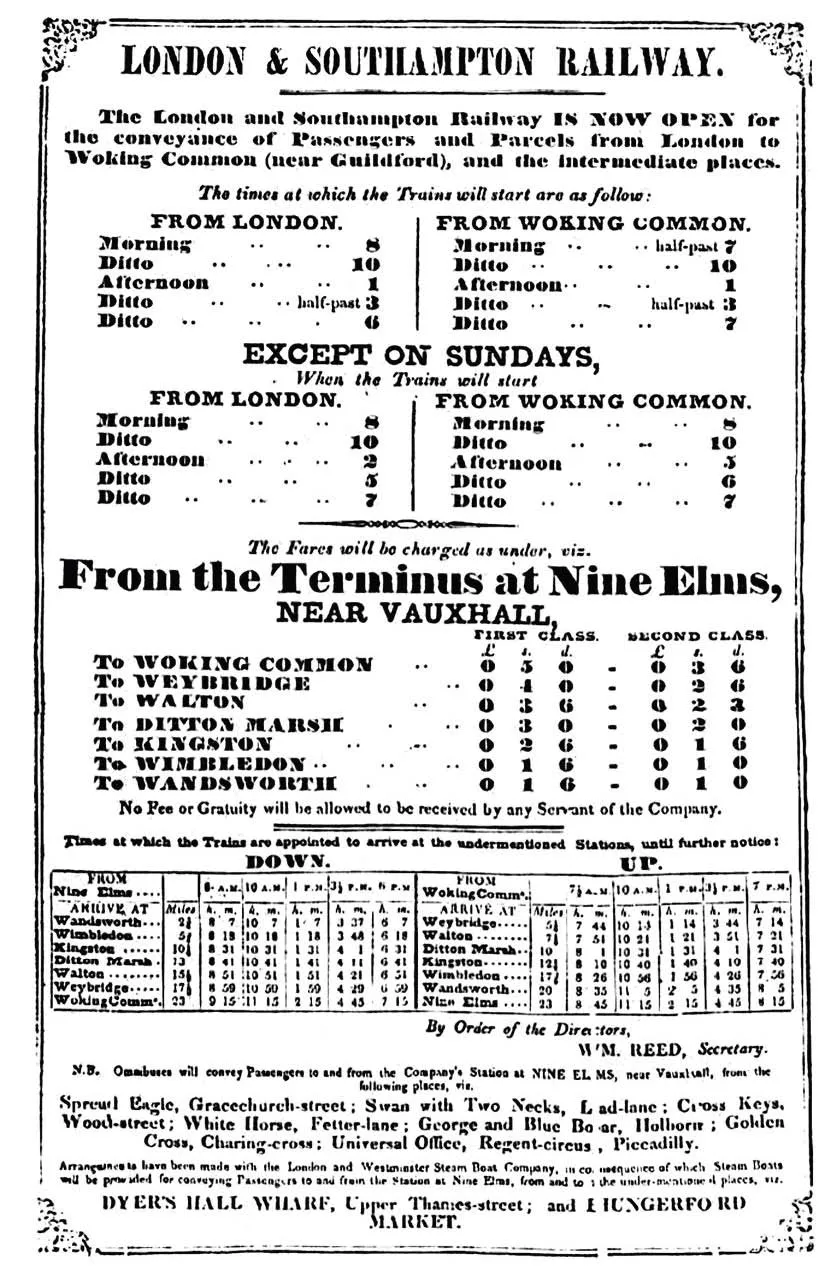

Locke also suggested the line be opened in sections so a profit could be turned whilst other parts of the route were being finalized. This approach was adopted, thus enabling the first stretch – between Nine Elms (near Vauxhall) and Woking Common – to open for service in May 1838, precisely in accordance with Locke’s revised schedule.

Joseph Locke

Born in Attercliffe, Sheffield, in 1805, Joseph Locke first trained to be a mining engineer, a role that would put him in good stead for his career as a master railway builder. At the age of eighteen he began to study under George Stephenson, and had a part in the construction of the Liverpool & Manchester Railway. After this he moved on to survey the Grand Junction Railway between Birmingham and Warrington.

So impressed were they with his work that the GJR directors hinted that Locke should take sole responsibility for the project; this suggestion greatly upset Stephenson. As well as lines in England, Locke also constructed railways in Scotland, France, Spain and Holland. He died in 1860.

Early Test Runs

In the weeks leading up to the official opening of the L&SR’s first section, a number of private trial runs were held, the first of which took place on Saturday 28 April 1838. The weather that day was perfect and spirits were high as Joseph Locke, along with the project’s directors, members of parliament and several noblemen, boarded carriages at Nine Elms – the L&SR’s first London terminus.

As the train chugged down to Woking Common, the fine weather allowed the VIP passengers a delightful view of the passing countryside, and many spectators gathered along the 23 miles (37km) of track to witness the historic event. The service reached Woking Common in forty-five minutes and managed the return journey to Nine Elms in forty-three.

On Saturday 26 May – two days before the L&SR’s official opening – another set of private runs took place, to which some 200 friends and family of the directors and shareholders were invited. When reporting on this excursion, The Manchester Guardian described the first-class carriages in considerable detail: