eBook - ePub

Oil, the State, and War

The Foreign Policies of Petrostates

Emma Ashford

This is a test

Compartir libro

- 360 páginas

- English

- ePUB (apto para móviles)

- Disponible en iOS y Android

eBook - ePub

Oil, the State, and War

The Foreign Policies of Petrostates

Emma Ashford

Detalles del libro

Vista previa del libro

Índice

Citas

Información del libro

In Oil, the State, and War, Emma Ashford explores the many potential links between domestic oil production and foreign policy behavior. By examining the behaviors of three types of petrostates–oil-dependent states, oil-wealthy states, and super-producers–Ashford sheds light on the diversity of petrostates and how they shape international affairs.

Preguntas frecuentes

¿Cómo cancelo mi suscripción?

¿Cómo descargo los libros?

Por el momento, todos nuestros libros ePub adaptables a dispositivos móviles se pueden descargar a través de la aplicación. La mayor parte de nuestros PDF también se puede descargar y ya estamos trabajando para que el resto también sea descargable. Obtén más información aquí.

¿En qué se diferencian los planes de precios?

Ambos planes te permiten acceder por completo a la biblioteca y a todas las funciones de Perlego. Las únicas diferencias son el precio y el período de suscripción: con el plan anual ahorrarás en torno a un 30 % en comparación con 12 meses de un plan mensual.

¿Qué es Perlego?

Somos un servicio de suscripción de libros de texto en línea que te permite acceder a toda una biblioteca en línea por menos de lo que cuesta un libro al mes. Con más de un millón de libros sobre más de 1000 categorías, ¡tenemos todo lo que necesitas! Obtén más información aquí.

¿Perlego ofrece la función de texto a voz?

Busca el símbolo de lectura en voz alta en tu próximo libro para ver si puedes escucharlo. La herramienta de lectura en voz alta lee el texto en voz alta por ti, resaltando el texto a medida que se lee. Puedes pausarla, acelerarla y ralentizarla. Obtén más información aquí.

¿Es Oil, the State, and War un PDF/ePUB en línea?

Sí, puedes acceder a Oil, the State, and War de Emma Ashford en formato PDF o ePUB, así como a otros libros populares de Politics & International Relations y National Security. Tenemos más de un millón de libros disponibles en nuestro catálogo para que explores.

Información

Categoría

Politics & International RelationsCategoría

National Security— ONE —

PETROSTATES

A TYPOLOGY

Since the end of World War II, the number of armed conflicts between states has plummeted. One group of countries, however, stands out in its continued aggression: oil-rich states, which have been at the heart of some of the most notorious and bloody conflicts in recent decades, from the Iran-Iraq War to the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, the Syrian civil war to the Russian seizure of Crimea. Among scholars there is a growing consensus, backed by statistical evidence, that petrostates are more likely than other countries to start wars. They matter in other ways too: these petrostates are among the world’s richest countries. Their production of a scarce and vital resource shapes the health of global markets and impacts international politics at the most fundamental level.

This book’s fundamental premise is simple: oil shapes the foreign policy of petrostates. These states—often dismissed as resource cursed or ignored altogether by work that privileges energy security concerns—are in reality a core cog in today’s international system. For simplicity, throughout this book, the term oil is used to indicate hydrocarbon production, notably oil and gas production.1 It is this hydrocarbon production and export that shapes the behavior of countries in war, diplomacy, economic statecraft, and covert affairs. We know that there are many links between energy security concerns and conflict.2 This book argues that there are also many potential links between domestic oil production and foreign policy behavior: some are based on wealth, others on the domestic effects of the resource curse, and still others on international market power. The evidence presented in this book suggests that petrostates have distinct foreign policy characteristics. There are strong and statistically significant links between oil and conflict across a variety of different metrics for oil production and export, for example. Oil wealth props up the global arms trade, provides states with diplomatic leverage, and allows them to support violent and nonviolent proxies. At the same time, our understanding of these relationships is heavily shaped by how we measure and define oil wealth. The book thus aims to provide a comprehensive exploration of the foreign policy of oil-rich states while also offering an original typology of the different kinds of “petrostates.”

In doing so, it fills a major hole in our understanding of the international implications of oil wealth. International relations scholars have too often treated oil-rich states as passive objects or as victims of energy-seeking states. Instead, this book echoes other recent work in contradicting classic understandings of energy and international security, which assumed that petrostates would likely be victims of an attack. Saddam Hussein’s 1991 invasion of Kuwait is perhaps the quintessential example: a regime, facing falling oil prices, sought to seize Kuwait’s oil fields and gain a larger share of the global oil market. In reality, it may be the only such example. Oil wars are rare, perhaps nonexistent.3 Yet the notion that oil is a uniquely valuable resource to be seized still looms large in the popular imagination. Take Donald Trump, who during his 2016 presidential campaign suggested the United States had erred in not “seizing” Iraq’s oil after the 2003 invasion.

This divergence flows in part from the myopic focus of politicians and scholars on energy security, a preoccupation rooted in the oil shocks of the 1970s. For politicians whose youth included gas lines and stagnant economic growth caused by oil shortages, such concerns loom large. Yet recent innovations such as fracking, liquefaction techniques, and even the simple creation of strategic petroleum reserves have reduced concerns for Western states.4 And as this book illustrates, energy security is not the only way in which oil influences international relations. It may not even be the most consequential. The following chapters instead explore the supply side of this relationship: the ways in which oil production impacts the foreign policy of petrostates. The evidence presented here shows that petrostates have distinct characteristics and tend to punch above their weight in world affairs. In recent years, for example, oil wealth has allowed underdeveloped Saudi Arabia, tiny Qatar, and undemocratic Venezuela to play key roles in international politics.

The question of why petrostates exhibit such distinct foreign policy behavior is trickier. Obviously, wealth greases the wheels; without their vast oil and gas profits, many oil-rich states would not be admitted to the ranks of groups like the G20, nor would they be treated as regional leaders. Wealth enables the purchase of arms and the sponsorship of foreign proxies. Yet wealth alone cannot explain why oil-rich states apparently choose the aggressive path so often. Surely it would be better simply to use that wealth to buy defensive weapons and build domestic prosperity? The explanations suggested by previous research are plausible but fall short. Revolutionary government, for example, may combine with oil wealth to drive a more aggressive foreign policy.5 But nonrevolutionary petrostates from Saudi Arabia to Russia to Nigeria have also shown aggressive tendencies, rendering this explanation at best incomplete. Perhaps the lack of a private sector in oil-rich states undermines the pacific effects of economic interdependence?6 Unfortunately, petrostates vary in the level of state economic control. Or perhaps oil exports are analogous to the nuclear stability-instability paradox, with the possession of oil wealth minimizing the consequences of military adventurism? As with other theories, there are contradictory cases and exceptions.

The reason, I argue, lies in how we understand and define a petrostate. In the popular imagination, the word petrostate conjures up clear images: a small, corrupt, non-Western, developing state such as Nigeria, Libya, Angola, or Saudi Arabia. Yet other types of countries could also be considered petrostates. Both Canada and the United States are among the world’s largest producers of oil and natural gas. Three members of the United Nations Security Council (China, Russia, and the United States) have each produced a substantial fraction of global oil supply at some point in the last forty years. For the first set of states, it seems likely that their pathological domestic politics—often described as the “resource curse”—cause their abnormal foreign policy behavior. For the latter, it seems far more likely that market power and their status as major global oil producers matters. Exploring the link between oil and conflict thus requires definitional and measurement choices.7 Should we measure the quantity of resources possessed by a state or the impact of resource production on the national economy? Do we measure the impact relative to the size of the economy or on a per capita basis? How about the producer’s relative impact on world energy markets? Petrostates vary widely across all of these dimensions, not to mention their non-oil differences—size, economic and institutional development, geographical location, and so on. The ranks of petrostates include nations as distinct as Russia, Oman, Norway, and Equatorial Guinea; to speak of them as one unitary bloc is fundamentally misleading.

THE ARGUMENT IN BRIEF

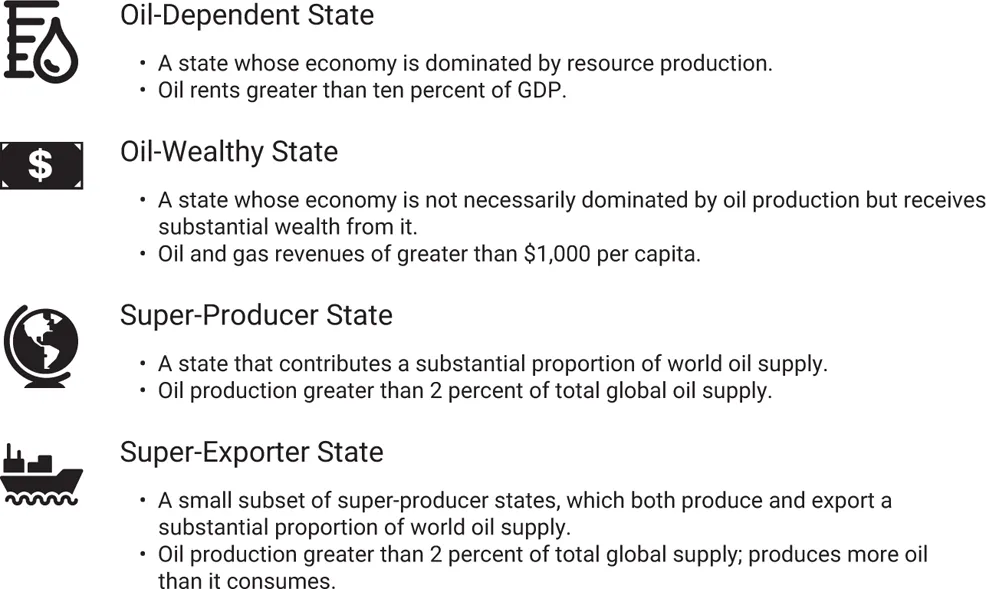

This book argues that foreign policy and oil are inextricably linked. Perhaps more importantly, it argues that oil shapes foreign policy outcomes in multiple ways. In essence, this is a definitional problem. The term petrostate is more anecdotal than practical. In choosing which natural resources matter, how to measure them, and what qualifies a country for petrostate status, an analyst is effectively selecting different groups of countries, which may have different foreign policy foibles. Major global exporters of oil undoubtedly act differently than poor countries dependent on the revenues from oil production. Yet both could plausibly be classed as petrostates. Rather than picking one definition, this book presents a broad picture of the ways in which oil shapes foreign policy across three different groups of petrostates: (1) oil-dependent states, those countries, sometimes poor, with economies dominated by oil extraction and production; (2) oil-wealthy states, those where oil provides substantial no-strings attached income; and (3) super-producer states, those states who control a substantial fraction of global oil market share—2 percent or more. The book also considers the tiny but important subgroup of super-exporters, states that are both super-producers and net exporters. Throughout the book, a net exporter is defined as a country that produces more oil than it consumes. At the intersection of super-producer and net export, therefore, super-exporters are in effect the world’s most important exporters. Because of the variety in petrostate types, I have structured this book not as an answer to one specific question but rather as a broad exploratory study of the many ways oil can shape the foreign policy processes and prospects of oil-producing states.

FIGURE 1.1. THREE TYPES OF PETROSTATES (AND ONE SUBTYPE)

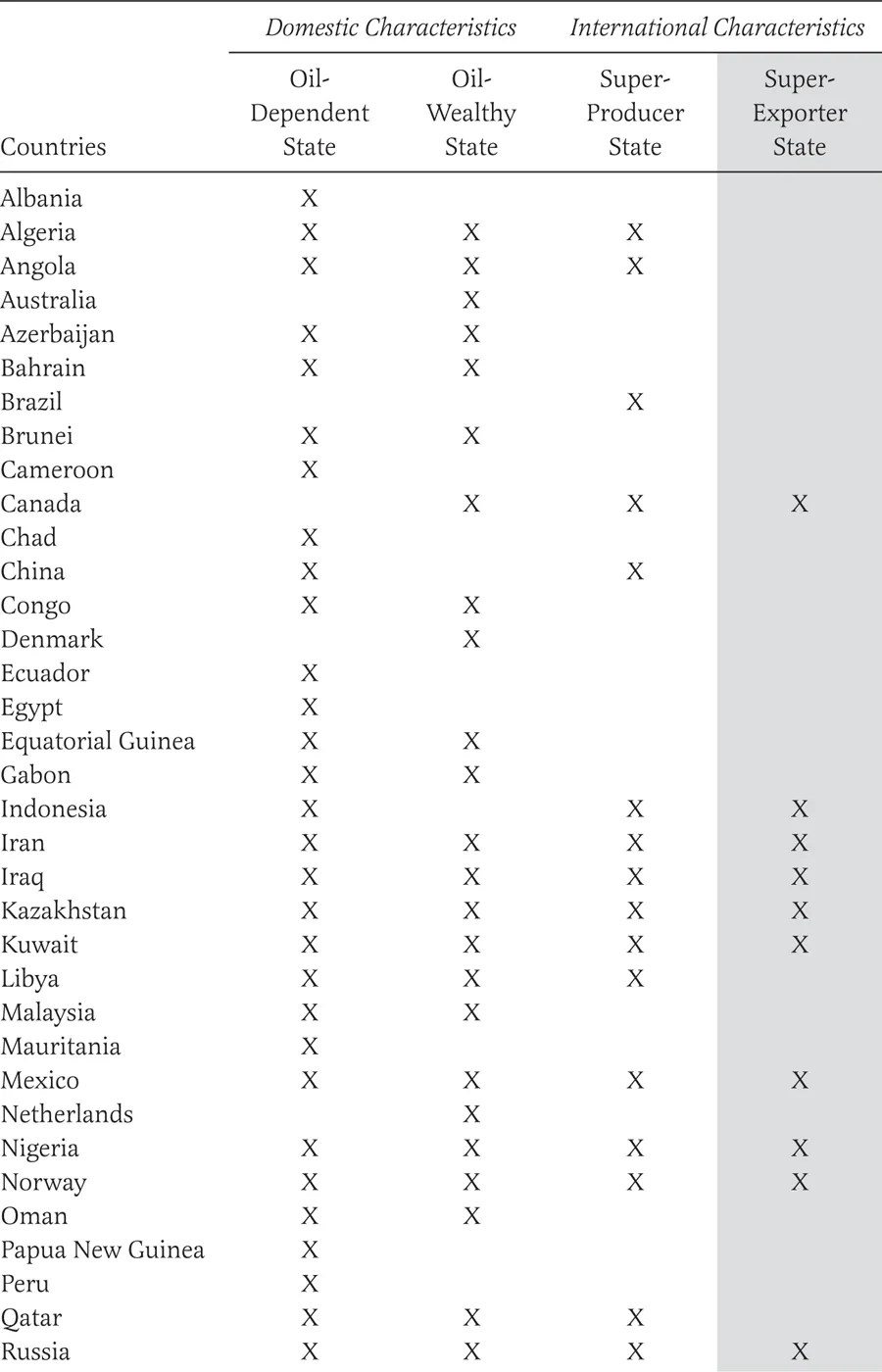

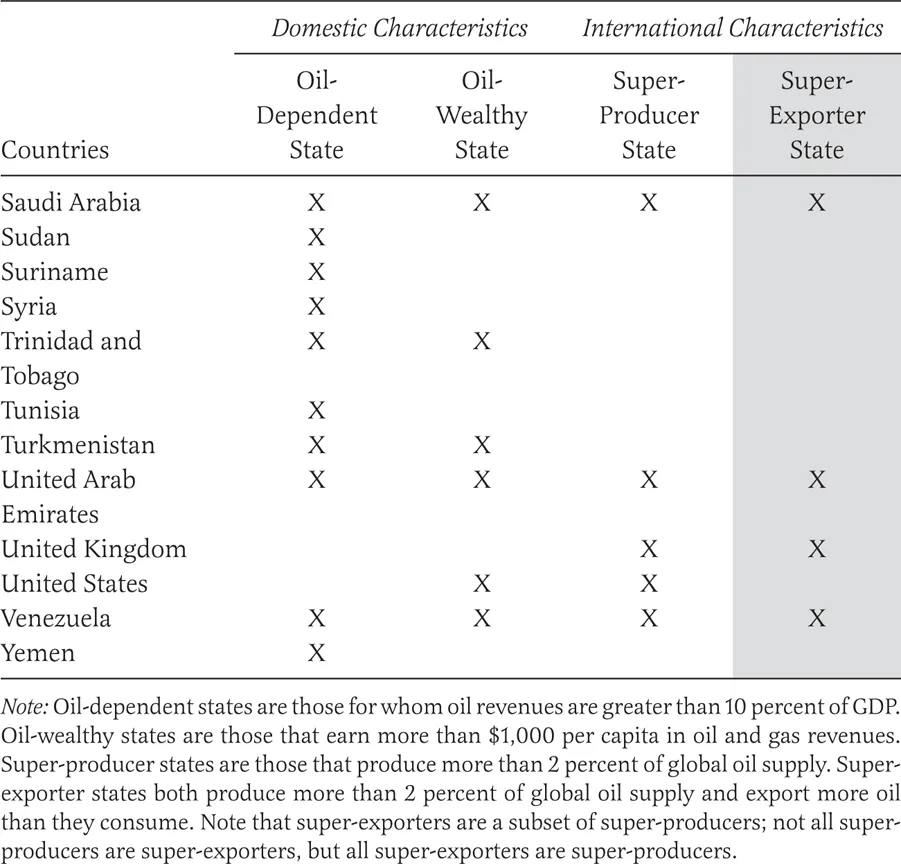

I do so by building on the foundation of these three core groups. For the rest of the book, I use the word petrostate sparingly and broadly; it includes any member of all three groups and is synonymous with oil-rich state. In general, however, I describe states more specifically: oil-dependent states, oil-wealthy states, and super-producer states. In addition to these three core types, I will also describe a subset of super-producers, the super-exporters. Though there is overlap in membership between these groups, each represents a distinct quality that can impact foreign policy outcomes. In brief, oil can make states incredibly wealthy, it can create dramatic domestic political and economic distortions, and it can add to a state’s international prestige or coercive capacity. Each of these factors—alone or together—can shape the foreign policy of a petrostate, and they should be considered the major avenues that link oil and foreign policy. In turn, I propose nine potential pathways: smaller channels within each avenue through which oil can shape the foreign relations of these states.8 The full membership of these groups can be seen in table 1.1, and an overview of the broad avenues and specific pathways linking oil to foreign policy can be found in table 1.2.

TABLE 1.1. PETROSTATES BY TYPE, 1960–2011

TABLE 1.1. (continued)

TABLE 1.2. CAUSAL PATHWAYS LINKING OIL AND FOREIGN POLICY

The simplest is wealth. Oil-wealthy states—which enjoy substantial income from their production of oil and gas—are in a lucrative business, with prices for oil ranging anywhere from $20 per barrel during the recent COVID crisis all the way to the $145 per barrel earned by oil producers before the 2008 financial crisis. Many producers have state-owned monopolies on oil and gas production, while others contract with large multinational firms to extract the resources. In either case, states receive a sizable chunk of the retail price of each barrel of oil.9 In 2012, for example, Russia produced around ten million barrels of oil per day, with a total value of approximately $408.8 billion; by 2014, just prior to the oil price collapse, Russian government revenues from oil and gas exceeded 52 percent of GDP.10 This wealth is self-evidently useful for foreign policy purposes. From weapons to foreign aid to violent proxies, leaders of oil-wealthy states simply do not need to make the same budgetary trade-offs as non-resource-wealthy states.

That same wealth can produce domestic economic and political problems, suggesting a second major avenue linking oil and foreign policy. The “resource curse” is not inevitable, but it does have a major impact on some states. Depending on the timing of state development, resource discovery, and exploitation, the resource curse can undermine institutional growth in oil-depe...