![]()

SECTION II

Wherein we take a look at Eastern Europe’s history, where its peoples (past and present) came from, and what forces shaped the region to be what it is today. This is also the part that tells you where all those street and beer names came from.

Kas var dziesmas izdziedāt,

Kas valodas izrunāt?

Kas var zvaigznes izskaitīt,

Jūras zvirgzdus izlasīt?

(Who can sing all the songs,

Who can utter all the languages?

Who can count all the stars,

Or collect the grains of sand on the shore?)

—Latvian folk song1

Riga, Latvia (IMAGE © ALEKSEY STEMMER / SHUTTERSTOCK)

A. INTRODUCTION: PREHISTORY

In the Beginning: Beginning with the beginning in history is always a problem, because you have to decide exactly when the beginning was. Humans and their ancestors have been in Eastern Europe for tens of thousands of years, but at which point did they become “Eastern Europeans”? Calling a Neolithic person an Eastern European is like calling someone from the Lenape/Delaware Indian tribe in the 16th century a New Yorker. Was there an Eastern in prehistoric Europe?

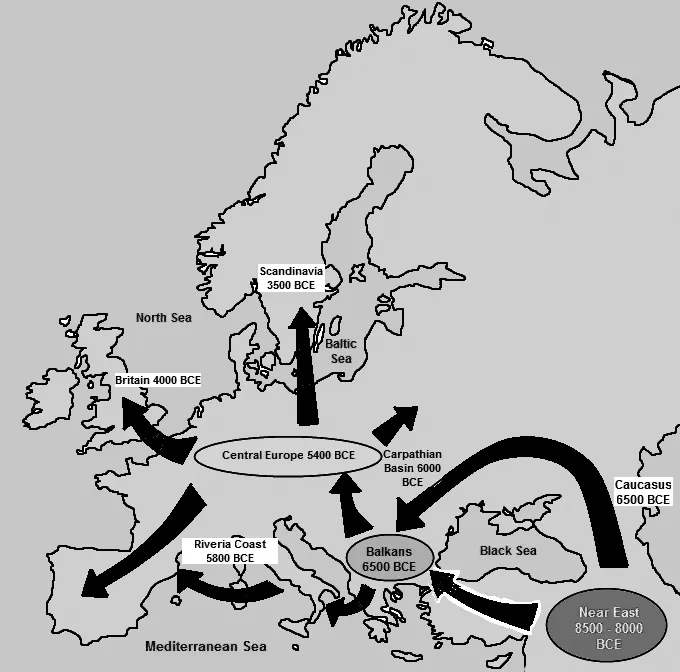

Figure 14. The Spread of Agriculture in Late Stone Age Europe1

In Figure 14 we see how agriculture is believed to have spread into Europe during the Neolithic, or Late Stone Age. This map is a generalization that simplifies what was likely a complicated process even within specific regions, but nonetheless, the basic flow from the western Middle East (i.e., Near East) to the Balkans through either Anatolia (modern-day Turkey) or the Caucasus and the Steppe are well established. The dates signify the approximate earliest local beginnings of agriculture. There were two basic outflows from the Balkans, northward into the Carpathian Basin and from there to Central Europe (and beyond), and another by sea to the coastal regions of the northern Mediterranean in what is today coastal Italy, France, and Iberia.

An important clue comes from the fairly new field of genetics, which tells us that modern-day Europe’s population is surprisingly (genetically) homogeneous, moreso than that of any other continent. Despite all the ethnic groups and countries, most present-day Europeans derive from just a handful of ancestral groups. And geneticists also confirm what the linguists have already told us—namely, that these groups span the “East-West” divide; prehistoric Europeans didn’t recognize an Eastern or Western Europe. Now, the further eastward in Europe one goes, the greater level diversity in DNA haplotypes (i.e., DNA gene groupings) one finds, but that just reflects a point I made earlier which is that Europe as a whole is a peninsula with Western Europe at its tip.

Put another way, Western Europe is connected to the Middle East, North Africa, and Asia by . . . Eastern Europe. An important implication of this fact is that for the first several thousand years of European history, an awful lot of the peoples, technologies, trade goods, and languages that eventually came to make up modern-day Western Europe probably flowed through Eastern Europe first. This may go all the way back to the very dawn of homo sapiens—modern-day humans—as many theories claim that modern humans (or our immediate predecessors, homo erectus) first entered Europe via either the Russian Steppe from Asia or the Balkans from the Middle East.

Figure 14 is an example of how Eastern Europe has served as the conduit through which people and their ideas have flowed into Europe for thousands of years. Most know that the Late Stone Age, the Neolithic, gave way to the Bronze Age around 3000 BCE, giving rise to the Aegean Sea–focused Minoan and ancient Greek civilizations that kicked off the Classical Age. However, the Bronze Age was preceded by the Chalcolithic or Copper Age, and its origins (in Europe) lay in modern Bulgaria around 3500 BCE, spreading like the agricultural societies northward to Central Europe and beyond. (Some archaeologists believe the Danube to have been a critical corridor for the flow of goods, technologies, and languages into prehistoric Central Europe from the Balkans.) This was the first metallurgical revolution for Europe, and its origins are in the Balkans. Indeed, in the summer of 2012, archaeologists discovered the ruins of what is to date the oldest prehistoric town in Europe, in Provadia, Bulgaria, about 21 miles (35 km) west of Varna. This settlement of 350 people is believed to date to between 4700 and 4200 BCE, or about 1,500 years before the start of the ancient Greek civilizations.2 In 2016, archaeologists found forty Venetian, Byzantine, and Ottoman shipwrecks off the Bulgarian coast of the Black Sea, some dating back to the 13th century but with wood, rope, and ceramics still amazingly well-preserved.3 This just highlights the crucial role Eastern Europe has played in Europe’s historical development before the formation of stable states in the medieval era. For millennia ancient trade routes criss-crossed Eastern Europe, while the Indo-European languages—whether they came originally by fierce Iranian Steppe warriors or docile Balkan farmers—also most likely entered Europe first through Eastern Europe. Eastern Europe is a sine qua non for European civilization.

USELESS TRIVIA: KEEPING UP WITH THE SKIS!

What’s with the “-ski” last name endings? Do all Eastern European family names end that way? Or even all Slavic names? Well, in short, no. Slavic names that end in “-ski” are actually adjectives, or more specifically adjectives made from nouns. “Jankowski” (Yahn-KAWF-skee), for instance, is simply an adjective based on the name “Jan” (John). And as adjectives in the Slavic languages, surnames reflect the gender of their owner: a female member of the Jankowski family has the last name “Jankowska.” (The “-ski” ending is a masculine adjective ending form.) For instance, in Russian Lenin’s wife was named Nadyezhda Krupskaya, but her father was Konstantin Krupsky.

But just how Slavic is that -ski ending, really? This is actually an old Indo-European family relic, and still survives in other Indo-European languages like the Germanic languages, for instance: Danske is Danish for “Danish,” while “Swedish” in Swedish is Svenska and Íslenska is “Icelandic” in Icelandic. It also survives in modern English (a Germanic language) as -ish—as in English, reddish, noon-ish, etc.—deriving from the Old English -isc and the Gothic –isks.4 It has even made it into Italian, likely via Italy’s many post–Roman Germanic invaders; the architect who built the famous dome on Florence’s cathedral was Filippo Brunelleschi—that eschi (pronounced “-eh-skee”) a common northern Italian surname ending. But it entered modern English in another way as well, imported from medieval French: Bureaucracy run amok is called “Kafkesque” (re: Franz Kafka), while something badly distorted from its intended or original form is called “grotesque.” Think about that the next time you crack a brewski.

Of course, nobody knew they were in Eastern Europe back then, because Eastern Europe wasn’t Eastern Europe yet—in the same way New York wasn’t New York yet—but sheer geography dictated that most of the basic elements that went into making European civilization had to flow first through Eastern Europe. This also means that Eastern Europe, from its earliest days, has an extremely complex, eclectic, and diverse history. Archaeologists and linguists in Eastern Europe today spend a lot of time sorting out the physical and cultural debris from thousands of years of constant flows of humanity through the region, attempting to sort out who was who and what belonged to whom (and when).

USELESS TRIVIA: THAT FRANK SINATRA LOOK

A Danish team of geneticists led by Dr Hans Eiberg at the University of Copenhagen discovered in 2008 that a single mutation in a gene called OCA2 arose sometime 6,000-10,000 years ago in humans living along the northwestern coast of the Black Sea (modern-day coastal Romania, Ukraine) giving them, for the first time in human history, blue eyes. Before this mutation, all humans had brown eyes, which most still do today. However, migrations from the Black Sea area spread this mutation across Europe, so that today about 40% of Europeans have blue eyes.

To give you an example of some of that diversity, let’s take a look at a people many are surprised to learn lived at one point in Eastern Europe: the Celts. That’s right—cue the Clannad music. Around 800 BCE the Celts began spreading into Western Europe from either Central Europe or possibly even the Steppe, eventually settling as far westward as Portugal and Spain, but remaining as far eastward as modern-day southern Poland, Ukraine, Slovakia, Czech Republic, Hungary, Croatia, Romania, and Bulgaria. Bagpipes are a common instrument throughout these areas. In fact, the British Isles were overrun about 4,400 years ago by a people from the Great Steppe called the Beaker Peoples—because of the unique shape of some of their pottery. These people showed up in Britain around the time Stonehenge was being built. They also overran Ireland, as was proven in 2015 when scientists from Dublin and Belfast analyzed the DNA of the 5,000-year-old remains of a woman found buried in Northern Ireland and those of three men buried 3,000–4,000 years ago in what is today County Antrim, Ireland. These studies confirmed that these ancient people contained genes found in most modern Irish, proving that the Irish derive from two primary migrations—one from the Fertile Crescent (modern Iraq) and the other from the Great Steppe in Ukraine. According to Dan Bradley, professor of population genetics at Trinity College Dublin, “There was a great wave of genome change that swept into Europe from above the Black Sea into Bronze Age Europe and we now know it washed all the way to the shores of its most westerly island.”5

The Celts at this time were divided into many tribes and spoke many languages, and had no common state or organization other than occasional loose alliances. The Celtic peoples are associated with the spread of Iron Age technology, and they’ve left their place names all across the region. For instance, the name for the historic western Czech province, “Bohemia,” derives from the Celtic Boii tribe that once inhabited the same real estate. The Danube River is believed to have gotten its name from the ancient Celts, as did the River Rába that flows from Austria to Hungary. Cities like Vienna, Bled (Slovenia), Legnica (Poland), Roman-era Pécs (in Hungary, known to Romans as Sopianae), and the Galatia region of central Turkey are also believed to have derived their names from the ancient Celts. In 2009, Polish archaeologists discovered the remains of an ancient 3rd-century BCE Celtic village near Kraków (KRAH-koof; Cracow). There are even historical indications that the Celtic Lugian tribe in what is today southern Poland requested and received Roman military aid in their struggles against the encroaching Germanic peoples in the late 1st century CE. Indeed, the continued migration of peoples from the east—especially the Germanic peoples—and the growth of the Roman Empire pushed the Celts westward and northward out of Eastern Europe, until they were confined largely to Spain, France, and the British isles, where their descendents still live today. In recent years, particularly in the Czech Republic, Celtic festivals have sprung up, some as nothing more than Irish or Scottish friendship festivals (and an excuse to guzzle beer), but some as forlorn efforts to try to “reclaim” a “lost” Celtic heritage.6 Just keep in mind that you have to say the Slavic pivo to order beer in Prague nowadays, not the Irish Gaelic beoir or the Welsh cwrw.

Figure 15. The Celtic Settled Regions of Europe, c. 800 BCE with Modern-day Country Names

USELESS TRIVIA: FUN SCIENCE PROJECTS AT HOME!

In 1933, a local schoolteacher, Walenty Szwajcer (Vah-LEN-tih SHVY-tser), was taking his students on a country excursion to nearby Lake Biskupin (Bee-SKOO-peen) in central Poland when he noticed something sticking out of the water. Szwajcer contacted noted archaeologist Józef Kostrzewski (YOO-zef Cost-ZHEF-skee), who examined the site and immediately organized an excavation. What Kostrzewski found was the stunningly well-preserved remains of an 8th-century BCE wooden fortified settlement from the late Bronze Age and early Iron Age. The site was named after the lake, and so today Polish schoolchildren learn about ancient “Biskupin” and take field trips there. Archaeologists link the site with the prehistoric Lusatian culture people of the late Bronze Age and early Iron Age, who lived from about 1300 to 500 BCE in what are today Poland, Slovakia, the Czech Republic, Austria, and Germany. Although 20th-century nationalists from all these countries have tried to claim the Lusatians as their own ancestors—during World War II, Nazi archaeologists from the SS Ahnenerbe tried to claim Biskupin as an “ancient Germanic” site—the truth is known today to be much more complex and nuanced. Today the site has been reconstructed and is open to the public as a museum, with young archaeologists-in-training spending summers in residence learning Bronze Age technologies and living practices while sharing their knowledge with schoolchildren and tourists.7

The point of this section has been to show that any attempt to understand Europe’s prehistory requires some in-depth understanding of Eastern Europe’s geography and prehistory, such was the contribution made by the region to the continent’s development. It is no exaggeration to say that Britain or France would not be what they are today were it not for the peoples, ideas, and goods that once flowed through ancient Bulgaria and Ukraine. In the late 20th century, it became common in the West to refer to the countries of Eastern Europe as “New Europe.” However, while there is some validity to this label in the se...