![]()

CHAPTER 1 >>>

Meeting the Gods

These four episodes of apotheosis from the Encounter underscore the roles of religion, material culture, and embodiment in early exchanges between Mesoamericans and Europeans. According to these accounts (all redacted by Europeans), the Aztecs identified Hernán Cortés and his companions as teteo (deities) and teixiptlahuan, their localized embodiments: first, in Francisco López de Gómara’s account, “the Mexicans”—a gathering of Amecamecan locals—associate the Spaniards with gods; second, the Tlaxcalans describe Cortés’s translator Marina/Malintzin as a goddess; third, the tlahtoani (speaker; ruler) Moteuczoma Xocoyotl (Lord Angry, Younger) identifies Cortés with Quetzalcoatl (Quetzal Feather Serpent); and fourth, Chimalpahin’s annotation reiterates and elaborates upon the Spaniards’ divine characterization established by López de Gómara.5 In addition to being identified as teteo in alphabetic texts, visual records substantiate the claim that Moteuczoma received Cortés with gifts befitting a god. The idea that Central Mexicans identified the Spaniards, Cortés, and Marina/Malintzin as gods held particular appeal for Europeans. Among the many fantastical accounts of the Americas that traveled to Europe, these circulated widely. In particular, the account of Cortés’s recognition by the Aztecs as one of their own deities became the prototype for other sixteenth-to eighteenth-century encounters.6

I begin with these accounts because they represent the incommensurability of Aztec cosmology and the European worldview. Rather than searching for the “true” history, an ambiguous enterprise in itself, I am exploring the substance of histories, the narratives about that which is said to have happened. Such stories are never divorced from the real and become in themselves historical agents.

Contact-period narratives, including Cortés’s letters and accounts compiled by López de Gómara, Sahagún, and others, present Mesoamericans in the context of confusing encounters, partial translations, and the ensuing establishment of colonial order. These narratives have a decidedly “contact perspective,” one that “emphasizes how subjects are constituted in and by their relations to each other. It treats the relations among colonizers and colonized … in terms of copresence, interaction, interlocking understandings and practices, often within radically asymmetrical relations of power.”7 Interpreting these texts as mythohistories with contact perspectives complicates—or perhaps clarifies—their reading by acknowledging that they both betray Mesoamericans and belie Europeans. In other words, those places where the texts seem most manipulated by the European worldview—such as the apotheosis episodes—or crucial to the colonial project—such as the exchange between Moteuczoma and Cortés—may be the precise points through which a clearer vision of the Mesoamerican perspective is possible.

In this chapter, I examine the implications of naming, translating, and revising mythohistories through alphabetic and visual records of the exchange that took place between Marina/Malintzin, Moteuczoma, and Cortés. First, I explore the Codex Mexicanus’s visual record of the gifts exchanged in comparison with Aztec practices of state gift giving. Then I address the question of Cortés’s apotheosis. I suggest that in this gift exchange and its aft ermath, contact between the Mesoamerican cosmovision and European worldview facilitated two related transformations: first, Aztec observers perceived Cortés as a potential deity teixiptla (localized embodiment), and second, Europeans saw Cortés being seen as a teotl (god). For the Europeans, Cortés’s apotheosis in the New World confirmed their suspicion of the natives’ misguided religiosity and created a powerful political advantage for the conquistador(s). For the Aztecs, the possibility that Cortés might become a teotl’s embodiment by wearing Moteuczoma’s teotlatquitl (deity belongings) and thereby initiate a ritual scenario through which he could be a sacrificial victim proved irresistible. More emphatically, were Cortés to have become the localized embodiment of a teotl, he would have presented Moteuczoma and the Aztecs with real-world possibilities of mythic proportions.

Gifts Fit for a God: Transferring Materials and Negotiating Meaning

The gift exchange between Cortés and Moteuczoma marks the initial clash of the conquistador’s European understanding of myth and history (or rather, their distinction) and the Mexica tlahtoani’s cosmovision. According to some accounts, Moteuczoma perceived Cortés’s landing at Veracruz in 1519 as the fated return of the Mesoamerican god Quetzalcoatl, who had fled to the East and was prophesied to return to rule his homeland again. For Cortés, the Mesoamerican belief that he was their returning god was purely fortuitous; perceived as a god, Cortés could play the role to his advantage. However, for the Aztecs and for Moteuczoma in particular, Cortés’s return signified the end of an era of rule and, ultimately, the end of their cosmovision. For us, the myth of Quetzalcoatl’s return complicates the process of understanding the implications of both the Encounter and the exchange.

The most complete alphabetic account of Cortés’s perception as Quetzalcoatl by Moteuczoma appears in Book 12: The Conquest of the Florentine Codex: General History of the Things of New Spain, a text compiled by Bernardino de Sahagún in the 1560s, nearly two generations aft er Contact. As I note above, scholars disagree about whether the myth is a pre- or post-Contact narrative.8 Camilla Townsend asserts that in The Aztec Kings, Susan Gillespie “has proven that the story as we know it did not exist until Sahagún edited the Florentine Codex in the 1560s.”9 Why, then, entertain the question of Cortés’s reception as a god? First, historically (and still today) some scholars identify Cortés and the gifts he received with Quetzalcoatl; second, whether or not Cortés was thought to be Quetzalcoatl, Mesoamericans initially referred to him and his men as teteo (gods); and third, even if the Mexicas never thought of Cortés as Quetzalcoatl or any other deity proper, this association became part of the larger contact perspective circulating in the mid-to late sixteenth century.

Furthermore, the precise meaning of teotl (god) complicates our understanding of how the Aztecs received Cortés and company. For sixteenth-century Nahuatl speakers, teotl was “a well-defined indigenous concept” in the “special vocabulary” of Aztec religion.10 And so to read teotl and hear “g/God” with associations other than those of sixteenth-century Nahuatl speakers misconstrues Moteuczoma’s response to the Spaniards’ appearance if, indeed, “when he learned that the ‘gods’ wished to see him face to face, his heart shrank within him and he was filled with anguish.”11 (In fact, differing emphases in the translation of this very passage illustrate how crucial Nahuatl concepts are in understanding Aztec religion. In this translation of the Florentine Codex’s Nahuatl text, León-Portilla emphasizes the identification of the Spaniards as gods through scare quotes; by contrast, Anderson and Dibble do not accentuate the word “gods”: “And when Moctezuma had thus heard that he was much enquired about, that he was much sought, [that] the gods wished to look upon his face, it was as if his heart was afflicted; he was afflicted. He would flee … he wished to take refuge from the gods.”12 Whereas LeónPortilla’s translation suggests that the Aztecs did not really and truly think of the Spaniards as gods, Anderson and Dibble leave the question open for their readers’ interpretation.) In much of the literature surrounding the question of Cortés as Quetzalcoatl, the connotations scholars attribute to teotl vis-à-vis their personal or comparative understandings of “G/god” cloud the issues involved in identifying Cortés as a teotl. As we shall see, teteo were marvelous and valuable entities with their own possessions, calendric associations, and exclusive occupations. Associating these qualities with teteo will aid us in understanding why Moteuczoma and other Nahuatl speakers identified Cortés and company as “gods.”

In the following pages, however, I am less concerned with weighing in on the question of whether the myth of Quetzalcoatl’s return is of pre-or post-Contact vintage than wiThexamining the stakes that underpin the question. Regardless of whether the my Thexisted pre-Contact, its appearance in the Florentine Codex documents its post-Contact importance. I am more concerned with the specific nature of Moteuczoma’s gift s, for, as I shall argue, a close examination of these gifts’ roles in an Aztec ritual of exchange highlights the decidedly symbolic nature of Moteuczoma’s religious obligations as tlahtoani. Specifically, Moteuczoma gives Cortés gifts appropriate for the teixiptla of a teotl, a ritual action with implications that exceed a simple welcome. This gift exchange thus offers a window into the historic moment in which both leaders’ visions were confirmed, for better and worse, and it reveals some of the gaps between Aztec and European epistemologies.

The Archive of Exchange

Although several accounts of the leaders’ (and their emissaries’) meetings exist, two sources, the Codex Mexicanus and the Florentine Codex, offer outstanding depictions of the gifts they exchanged. The Florentine Codex provides extraordinarily detailed descriptions of the teotlatquitl (god’s belongings) in two languages, and the Codex Mexicanus is the only extant visual record of the items exchanged by both leaders.

The Florentine Codex contains the most elaborate description of the gifts Moteuczoma gave Cortés, and the richest accounts of the teotlatquitl appear in the Spanish text. In marked contrast to the majority of the Florentine Codex, the Spanish descriptions of the deity attire include much more detail than those in Nahuatl, and they provide the reader with a truly exceptional sense of how each teotl’s attire would have been worn. For example, the scribes explain that a turquoise mask with serpents twisting along the bridge of the nose “was set in a large high crown full of very beautiful, long, rich plumes, so that when one put the crown on one’s head one also put the mask on one’s face.”13 Details like these give the reader the impression that Sahagún, his informants, or scribes had access to a source—whether material, pictorial, oral, or alphabetic —from which they drew rich descriptions of the elaborately worked masks, capes, shields, and headdresses.14 Although it may be impossible to determine the source of these descriptions, they describe the exclusive attire of specific teteo, including Quetzalcoatl, Tezcatlipoca (Smoking Mirror), and Tlalocan Teuctli (the Lord of Tlalocan), among the gifts given Cortés. By contrast, the Codex Mexicanus presents a more complete picture of the exchange. Though it lacks the Florentine Codex’s level of detail, the Codex Mexicanus provides a visual context for the exchange.

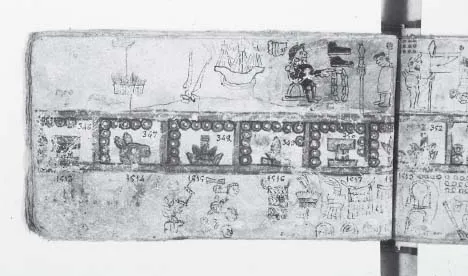

The Codex Mexicanus (1571–1590), a pictorial manuscript painted on bark paper bound like a European book, contains the only images of the gifts exchanged by both Moteuczoma and Cortés (Figure 1.1). Above a row of date signs, Cortés sits in a European-style folding chair facing one of Moteuczoma’s ambassadors, who wears a tilmahtli (cloak). Cortés hands his gifts for Moteuczoma to the Aztec intermediary: a beaded necklace, European shoes, and a steel-tipped lance (Figure 1.2). Moteuczoma’s gifts for Cortés appear below the sequence of date signs and include “a beaded cape, two feather headdresses, two feather cloaks, five disks of turquoise mosaic, a tunic and two shields (Figure 1.3).”15 Likely drawing on the Florentine Codex’s description of numerous gifts, Elizabeth Boone identifies the vestments of the god Quetzalcoatl among Moteuczoma’s gifts.16

Based on the extensive descriptions of the gifts in the Florentine Codex, however, it seems probable that the Codex Mexicanus depicts select or representative items from the teotlatquitl Moteuczoma gave Cortés. In fact, the Codex Mexicanus may focus on gifts decorated in greenstone or quetzal feathers, perhaps because their blue-green color reflected their high value. Taken together, these contact perspective texts document the luxurious teotlatquitl, literally the belongings of the teteo, that Cortés received from Moteuczoma.

Aztec rites of hospitality required that Moteuczoma provide the Spaniards withan appropriate greeting. In his exchange with Cortés, Moteuczoma employed a traditional understanding of relationships between rulers and of the ritual production of teixiptlahuan in order to welcome a potential ruler cum-god. Furthermore, the images suggest that both the tlahtoani’s ceremonial gifts and the conquistador’s reciprocation held the possibility of double meanings.

Gifts Fit for a God: Precedents and Implications

Rituals of exchange and bodily adornment emphasized the powerful rela...